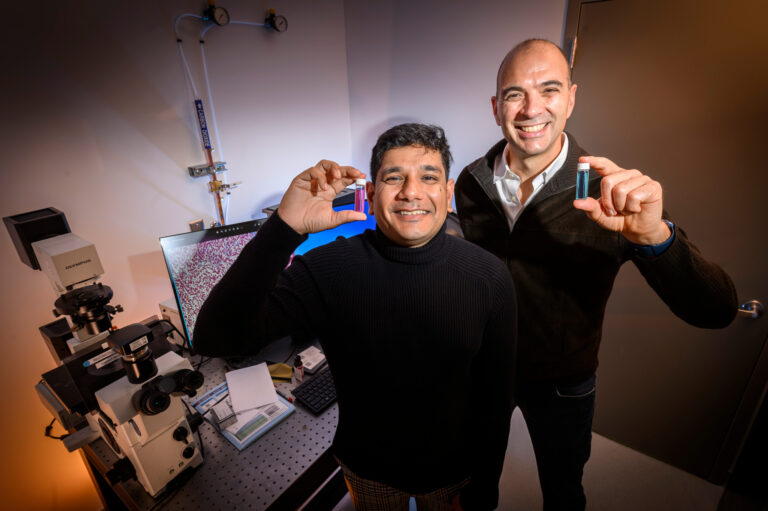

University of Illinois researchers are working on a way to make it easier to locate and remove cancerous tumors in the body.

When it comes to locating tumors to extract them during surgery, doctors currently inject nanoparticles into the body that are supposed to help them find the cancerous tissue during an imaging scan.

But postdoctoral researcher Indrajit Srivastava says the nanoparticles often collect in the liver rather than on the tumor, because the body recognizes them as foreign objects and sends them to the liver to be cleaned out of the blood.

To combat this, Srivastava’s team has been testing nanoparticles coated in red blood cell membranes.

As shown during trials in mice, these nanoparticles circulate in the blood, then stick to tumors and fluoresce, emitting light that can be seen with an imaging camera.

“It’s sort of like throwing a little beacon of light in the room, and that beacon goes and has a magnet and it attaches to another magnet,” explained Professor Viktor Gruev, another one of the researchers. “You’re in a dark room and you can find what you’re looking for.”

Another problem the researchers have been working on is the efficiency of the imaging. With the current tools, doctors can only search for a single stage of cancer during a scan.

Srivastava and Gruev’s team have been testing a combination of nanoparticles. One targets a biomarker prevalent in early stage cancers, while the other is aimed at a biomarker that’s common in late-stage cancers.

This would allow doctors to find both early and late-stage cancers with one scan, rather than needing to wait hours or days for a pathologist to weigh in on a sample taken from the patient, Srivastava said.

“With our platform, you can have a picture in real-time when you’re doing the surgery,” he said. “While the surgeon is operating, they can tell that this is an aggressive cancer and this is not an aggressive cancer, which I feel like would be a game-changer in the next five to 10 years.”

The inspiration

Once the nanoparticles have found their way to the tumor, they emit light, but it’s not light that can be seen by human eyes. That’s where the cameras developed by Viktor Gruev and his team come in.

Gruev teaches electrical and computer engineering at the University of Illinois. But ten years ago, he was working with marine biologists, studying the eyes of mantis shrimp, which can see far more wavelengths of light than human eyes.

These shrimp are believed to have the most complex visual systems in the world, and Gruev worked to develop cameras that imitate their eyes.

“Imagine having a camera that sees more colors and different properties of light,” he said. “Once we mimicked that part, we sort of started thinking about, ‘What is it this camera can tell us differently than what color cameras do?’”

His shrimp-inspired cameras are able to detect the light coming from the nanoparticles, which lets surgeons get a complete picture of the tumors they’re trying to extract.

He said that this technology could also make it more likely that surgeons could remove all of the cancerous tissue with one operation, really making operations easier and more efficient for doctors and improving outcomes for patients.

“Surgery hasn’t changed, I would argue, for more than a hundred years,” Gruev said. “The primary way the physicians do the job is more or less the same as 100 years ago. They use their hands, their touch, and their eyes to identify tumors.

“And that’s where the problem is. They’re not going to be able to identify all the tumors, especially if they’re smaller or in some distant places. So hopefully this is where our technology can help them.”

Gruev said he and other researchers are now looking more toward the natural world for inspiration to keep tackling modern problems and pushing technology forward.

“Working with marine biologists 10 years ago helped me design these cameras,” Gruev said. “And now it’s pushing different frontiers in areas that if you would have asked me 10 years ago, I would’ve been oblivious about.”