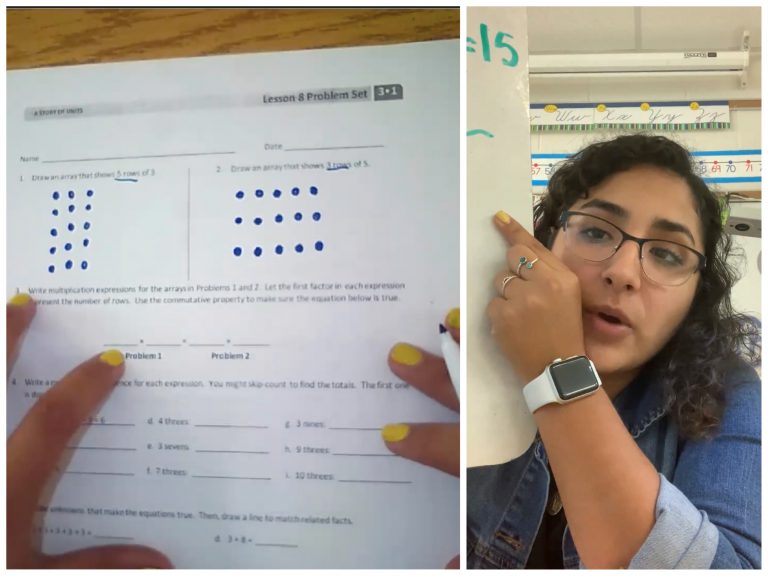

In her virtual classroom last fall, Erika Jimenez struggled to teach her third graders how to read an analog clock in English. In person, the lesson would have been challenging for the predominantly Spanish-speaking class. Over Zoom, the students were visibly frustrated. Some even cried.

But those were just the students paying attention. Jimenez knows some of her kids play Xbox or are on their phones while in class. Others have younger siblings distracting them from instruction.

Jimenez, a senior studying bilingual education at Illinois State University, is frustrated: She has to troubleshoot technical difficulties while getting students to focus on the course material.

While some state requirements for teacher licensing were changed due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the switch to remote learning for student teachers is still challenging. Many also worry they aren’t receiving the experience or skills needed to run their own classrooms.

Meanwhile, an increasing number of Illinois teachers are retiring, exacerbating the state’s teacher shortage. Additionally, student teachers of color are trying to enter an industry where they make up less than 20% of the workforce and can face additional licensing barriers due to the associated costs. And student teachers are trying to navigate changing requirements and working with unmotivated students. While an influx of new teachers are sorely needed across Illinois schools — even more so now than before the pandemic — many student teachers are struggling to navigate both changing requirements and working with unmotivated students.

“Honestly, the most classroom management that I’ve learned this semester has to be just muting our kids on Zoom, and that’s not how it is in the classroom,” she says.

The Illinois State Board of Education requires teachers graduate from an accredited program and participate in approved clinical experiences, which include a semester of student teaching in person, virtually or some combination of both.

Jacob Dunskis student taught this past fall at Carlinville High School. Dunskis, who just graduated from Blackburn College — a liberal arts college located about 50 minutes south of Springfield — spent the first half of the fall semester teaching literature in person to ninth and 10th grade students. He says the high school was able to open in the first place because of its small size and access to resources.

In the latter half of the semester, the school switched to virtual instruction because of rising COVID-19 cases in the surrounding community. When school went online, Dunskis says his students were unmotivated. Many didn’t attend class, he says, and he struggled to get responses to emails. He says a larger percentage of his students failed than normal.

Dunskis says he knows his students have a lot going on, but “to see students just not participating in their education on such a massive scale has been incredibly disheartening.”

While student teachers struggle to engage their pupils remotely, they also have to meet the state’s standards for licensing. ISBE changed the assessment portion of the licensure process due to the pandemic, which includes content tests for student teachers and the Teacher Performed Assessment (edTPA).

Content tests assess prospective teachers in their respective academic areas of expertise, says Nancy Latham, the executive director for the Council of Teacher Education at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Before the pandemic, the content test had to be passed before one could begin student teaching.

Because of complicated testing site logistics, content tests now only need to be passed before a teacher applies for licensure — not before student teaching.

The edTPA requires students create lesson plans, record themselves teaching, and write reflections of their classroom experiences to submit to third party educators — all of which can take weeks to complete. Under the governor’s executive order, the edTPA requirement for 2020 spring and fall graduates was waived.

Latham says ISBE waived this requirement on a semesterly basis under the governor’s emergency declaration. Up until recently, it was still unknown whether teacher candidates in the spring semester, which starts as early as this week, would have to complete the edTPA — causing confusion for many prospective teachers.

A spokesperson for ISBE, Jackie Matthews, wrote via email that the edTPA requirement will continue to be waived as long as the state remains under the governor’s public health emergency.

Dunskis completed a version of the edTPA because his university required it.

“I hate the edTPA — I think a lot of teaching candidates do and college professors do,” Dunskis says. “And it’s because it doesn’t really reflect how good you are as a teacher, it kind of reflects upon how good you are at filling out forms.”

In Illinois, the edTPA has close to a 96% pass rate, but Jason Leahy, executive director of Illinois Principals Association, says studies show that the edTPA can be a barrier for teachers of color.

An August report from University of Illinois researchers found the edTPA “imposed significant monetary ($300-$1,200 per applicant) and time investments, which had a disproportionate effect on minority prospective teacher candidates.”

Since it was instituted in the state in 2015, the edTPA has been a controversial performance assessment tool to measure teacher candidates’ success. Recent attempts to remove the requirement for Illinois teachers have not been successful.

Georgia removed the edTPA from its licensure process over the summer following statewide e-learning in the spring. At the time, the state’s superintendent of schools said COVID-19 showed that assessment of teachers’ preparation and skills extended far beyond a single performance test.

Matthews wrote that ISBE plans to finalize a proposed provision this month that would not reinstate the edTPA until six months from when the public health emergency is lifted.

Leahy, with the Illinois Principals Association, says he personally didn’t put much “stock into the assessment” when he hired teachers, turning instead to the feedback from cooperating teachers and university supervisors since they work closely with teacher candidates. He says the edTPA can be a “nice reinforcement” of the candidates’ skills, but other parts of the student teaching experience can determine if prospective teachers are prepared to lead their own classrooms.

As for Jimenez, she says it was a relief to learn she didn’t have to complete it.

“Instead of worrying about the exam and the testing and reflecting,” she says, “now, I can actually focus on the students.”

This year, ISBE along with two state professional educator associations used federal funding from the CARES Act funding to establish a virtual mentorship program to help first-year teachers throughout the state.

Leahy says this type of mentorship needs to be sustained and extended to all first-year educators because it will lead to higher rates of teacher retention and better outcomes for students.

Jimenez, a first generation college student, has found mentors in her colleagues who come from similar backgrounds. As a Mexican American, she says being surrounded by other educators who look like her for the first time in her life has been rewarding.

She says she’s proud of herself for making it this far and for the educator she is becoming, but the circumstances of the job and the pandemic have made her and her colleagues feel like they should be doing more for their students.

“Seeing them talk about how they really care about their students, but they feel like they’re not doing enough — it breaks me,” she says. “And I know because I feel the same way.”

Editor’s note: This story has been corrected to reflect that the mentorship program offered by ISBE is available to all teachers — not just those in high needs areas.