State touts diversity report, but most specialty cannabis businesses have not become operational

While Illinois’ cannabis market is booming and the state has made progress in diversifying new licensees, significant hurdles remain for businesses hoping to enter the expanding market, according to an independent review of the industry.

Celebratory news releases have marked several industry successes in recent months – the state saw the opening of its 100th social equity cannabis dispensary and surpassed $1 billion in cannabis sales in 2024.

Gov. JB Pritzker, since signing the Cannabis Regulation and Tax Act in 2019, has often repeated that social equity is at the core of Illinois’ cannabis program. In July, he praised a newly commissioned, independent diversity report regarding the industry that identified progress – and hurdles – for the stated diversification goal.

The independent diversity study – commissioned by the state at a cost of $2.5 million by Peoria-based Nerevu Group consulting firm – found that while the state has awarded more licenses to women and people of color than any other regulated market in the United States, white men are still the demographic most likely to have a cannabis license in Illinois.

But the Department of Agriculture’s most recent licensee operation status list shows only about 30% of businesses awarded specialty cannabis licenses are operational. And for some social equity applicants, turning the licenses into a functioning business has been difficult.

Many of the lofty goals set by the law have been slow to materialize for social equity business owners – those who have lived in an area that has been historically impacted by the war on drugs, or if they have been personally impacted. Through last summer, of the almost 50 dispensaries opened by social equity licensees, only 15 were owned by people of color, according to last year’s annual cannabis report from IDFPR.

While state data shows that minority- or woman-owned businesses hold most lower-level and specialty licenses, more than three-quarters of cultivation licenses are held by companies owned by white men that have dominated the industry since cannabis was legalized for medicinal purposes.

Barriers to funding

The first cannabis dispensary licensed through the state’s social equity lottery program did not open until late 2022 – nearly a decade after the first cannabis plants and companies took root in Illinois amid its 2013 legalization for medicinal purposes.

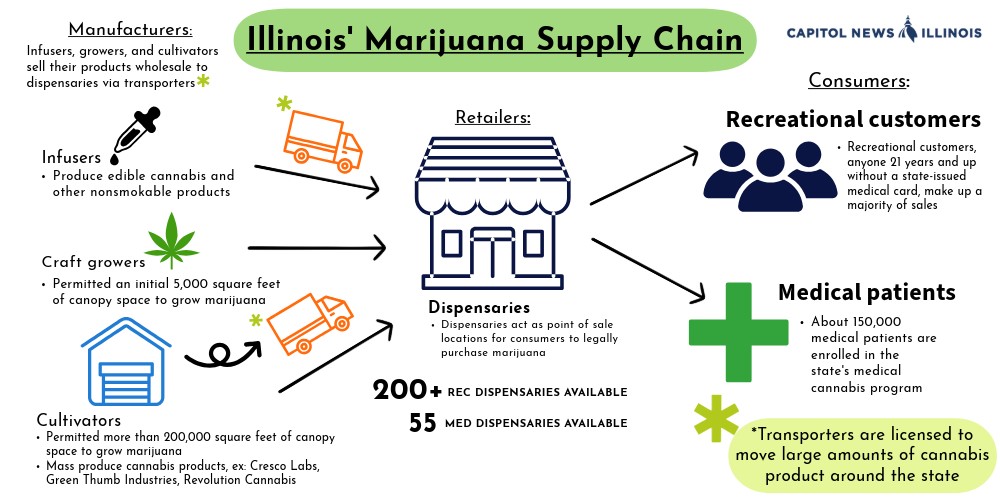

As part of the 2019 legalization law, lawmakers created a “craft grow” license category that was designed to give more opportunities to Illinoisans hoping to legally grow and sell marijuana. However, existing cultivation centers – often owned by large publicly traded companies – that grew cannabis for the state’s medical program since as far back as 2014 were approved to grow cannabis for adult use dispensaries in late 2019.

The report commissioned by the state’s Cannabis Regulation Oversight Office found numerous challenges facing craft grow businesses. For starters, marijuana remains federally illegal, making banks and financiers more hesitant to invest in the industry.

Reese Xavier was awarded a craft grow license through the state’s social equity lottery in 2021, following a highly detailed application process that took him roughly three months to complete. Three years later, even as a recipient of a loan through the Department of Commerce and Economic Opportunity, he is still without enough capital to build out his brick-and-mortar site for growing cannabis plants.

Xavier is still “all in,” but said it’s been difficult to find the necessary funding to begin construction – perhaps the most common and prominent hurdle small cannabis businesses face, as launching grow centers or dispensaries costs millions of dollars.

“A common myth – that I know to be a myth now – was you don’t have to worry about the money. ‘If you win the license, the money will come to you,’” he told Capitol News Illinois. “That is absolutely not true. That’s one of the biggest challenges, access to capital.”

Last year, through DCEO’s social equity loan program, the state provided about $20 million in forgivable loans to a total of 33 licensed craft growers, infusers and transporters. While nearly all of the transporters who were awarded loans are operational today, more than one year later, only 40% of the craft grow and infusion businesses that received loans are up and running.

Last month, DCEO announced more than $5 million in loans to 17 businesses that own more than 20 dispensaries across the state, a majority of which are already open for adult-use sales.

Erin Johnson, the state’s top cannabis regulator, told Capitol News Illinois that while state agencies have had to jump federal hurdles, more loans will be available later this year for specialty licensees.

“Capital is a huge challenge for our agencies, given the fact that cannabis is still federally illegal,” she said. “By the end of this year, the application will open up to provide another $40 million in direct forgivable loans to all license types.”

Large companies’ leg up

Xavier owns a license to grow marijuana and make products derived from the cannabis he grows, such as oils for vaporizers and tinctures, which he can then sell wholesale to dispensaries, which then sell products retail to customers.

Specialty marijuana businesses – several categories which were added to state law when lawmakers legalized recreational cannabis – can be licensed to grow, infuse or transport marijuana products. That means these businesses have fewer avenues to profit as compared to companies that own all-encompassing cultivation centers.

Nearly two dozen major operators (including one nonprofit, Shelby County Community Services in Shelbyville) are licensed to operate cultivation centers in Illinois. There, they can grow, cure and package marijuana flower, along with other products, like edible cannabis, that they sell to dispensaries.

One challenge for craft growers is that they are limited to 5,000 square feet of canopy space to grow cannabis flower, which “does not generate sufficient profit necessary to secure financial backing,” per the report. The 5,000-square-foot canopy condition also “restricts the ability to produce enough cannabis to build brand loyalty throughout the Illinois market,” according to the report.

The Cannabis Regulation and Tax Act allows the Department of Agriculture to increase canopy space for a craft grower up to 14,000 square feet in 3,000-foot increments.

Meanwhile, cultivation centers have up to 210,000 square feet (roughly the size of a city block) to grow cannabis. Some operators own multiple cultivation centers, meaning they can produce anywhere from 15 to more than 120 times the amount of cannabis as an individual craft grow company.

This restriction on craft growers contributes to slow economic growth for craft licensees, according to the state-commissioned report.

Of the 87 licenses awarded to craft grow businesses, only 21 have been approved for construction and 16 of those businesses are operational, according to the Department of Agriculture. Xavier’s craft grow cannabis business, HT 23, is one of five that have been approved for construction but are not yet operational.

The state-commissioned report found flaws in the craft grow business compound for infusers.

“Infusers require a product known as cannabis distillate, which comes exclusively from commercial cultivators,” the report reads. “Technically, craft growers may produce distillate to sell to infusers, but many reported they are unlikely to do so given their limited canopy space.”

It identified other distillate options for infusers as prohibitively expensive.

“Many infuser participants said cultivators charge far above fair market price for distillate,” it continues. “They also stated cultivators inconsistently price their distillate and you must have a preexisting relationship with a cultivator to get a fair deal.”

Xavier said he’d like to have more direct conversations with Illinois lawmakers and regulators so they can understand the challenges licensees face.

“These things seem to be simple, and that’s what we’re learning: Everything isn’t simple,” Xavier said, noting he’d like to see the state spending “more time and energy” listening to social equity licensees.

Bills introduced during the Illinois General Assembly’s spring legislative session aimed to address issues for small cannabis businesses, like requiring cultivators set aside an amount of concentrate for infusers to purchase, but many of them stagnated without enough support.

Other criticisms

A July report by the National Black Empowerment Action Fund, a national advocacy group supporting Black entrepreneurship, criticized Pritzker for allowing a legal framework they say has benefitted major corporations over aspiring Black business owners.

The report contends too few dispensary licenses have gone to businesses owned by people of color.

“Pritzker talked the talk, he never walked the walk,” the NBEAF report states, “instead, he let white owners gobble up the most lucrative parts of the market.”

Johnson, the state’s cannabis regulation oversight officer, said the rate of minority dispensary ownership has increased from 20% to about 50% of the state’s dispensaries that have opened since 2020.

For businessowners who do not qualify for the state’s social equity criteria themselves, state law considers those who hire a workforce with at least 50% fitting the state’s benchmark for being impacted by the war on drugs as social equity businesses. However, the number of social equity businesses that qualify as such based on the makeup of their workforce, is unknown even to Johnson, who said state law allows licensees to keep that information confidential.

The NBEAF report found that social equity dispensaries accounted for less than 4% of Illinois’ cannabis industry’s entire fiscal year 2023 sales of more than $1.5 billion.

While the 2023 Annual Cannabis Report from Illinois Department of Financial and Professional Regulation “expects this number to continue growing” as more social equity dispensaries open, NBEAF argues it has taken too long for licensees to gain their footing.

Editor’s note: This is the second in a two-part series on the state’s marijuana industry. View the first part here.