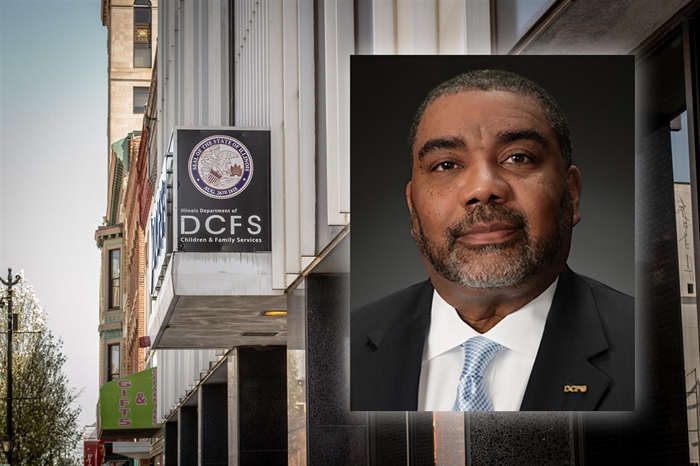

Illinois Department of Children and Family Services Director Marc Smith will resign effective Dec. 31, he told colleagues in an all-staff town hall meeting Wednesday morning.

For years, critics had called on Smith to resign or be fired, amid legislative hearings, contempt citations, a murdered child protection investigator and the highest number of children who died after contact with the agency in 20 years.

Smith announced his voluntary resignation Wednesday via a livestreamed video to agency staff, noting that his decision came after discussions with family and colleagues within the child welfare system.

“Sometimes the media sometimes politicians, sometimes critics take an opportunity of tragedy to move an agenda,” Smith said during the call. “But we understand that we are here for the day-to-day. We are here, at all times, for all of our kids and we will serve them and care for them with compassion, seriousness, and honor.”

The resignation came after another scathing audit of the agency was published last week, finding that in recent decades, DCFS repeatedly violated state laws meant to protect children from abuse and neglect.

Smith’s announcement was one of three agency head departures made public by Gov. JB Pritzker’s office Wednesday. Theresa Eagleson, who has led the state’s Department of Healthcare and Family Services since January 2019, will leave her post at the end of the year, according to a news release from the governor’s office. Illinois Department on Aging Director Paula Basta will also retire in December.

“Theresa, Paula, and Marc reflect the best of state government – people who have sacrificed to help millions of constituents through their dedication to service,” Pritzker said in a news release. “Despite the excellent quality of the candidates who will fill their shoes, their full impact on state government can never truly be articulated or replicated, and I thank them for their years of service.”

The personnel announcements come less than a month after Pritzker’s office announced Deputy Gov. Sol Flores, who oversees Illinois’ health and human service agencies – including DCFS, DHFS and the Department on Aging – will be leaving in mid-October. Grace Hou, the current director of the Department of Human Services, will be promoted to that role.

Audit findings

The audit released last week revealed repeat findings – going back decades – that directly impacted the care and safety of children.

The audit found DCFS violated state law by:

- Failing to notify law enforcement within 24 hours of the death, serious injury or sexual abuse of a child. Audits have included similar findings seven times throughout the past decade.

- Failing to complete investigations of abuse and neglect within statutory timelines. Audits have included similar findings 17 times since 1998.

- Failing to respond to a report of abuse or neglect within 24 hours, putting the child in further jeopardy. Previous audits have included similar findings 17 times since 1998.

- Failing to notify schools of credible sexual and physical abuse.

- Failing to timely notify prosecutors of test results for children born having been exposed to controlled substances.

- Failing to alert the Illinois Department of Public Health and the Illinois Department of Human Services when there were allegations of abuse or neglect of a hospitalized child, including a psychiatrically hospitalized child.

House Republicans renewed what have been repeated calls for Smith’s removal after the audit’s release. In January 2022, Republicans called for hearings after Smith was found in contempt of court 12 times by a Cook County judge for failing to put abused children in appropriate placements. The judge faulted Smith for holding children in psychiatric hospitals for months after the court had ordered them to be removed.

At the hearings that led to the contempt charges, Cook County Public Guardian Charles Golbert, who represents DCFS wards in court, said his office had raised concerns about inappropriate placements since 2016. Cook County Judge Patrick T. Murphy took the unprecedented step to find Smith personally in contempt of court.

Some of the contempt charges were purged when the agency moved the children to appropriate placements. Others were vacated by an appellate court which ruled that Smith did not willfully disobey the court’s order, but simply did not have the ability to comply with it, because DCFS didn’t have enough beds in places like group homes, shelters or other foster care placements.

Golbert has been one of Smith’s toughest critics and noted that the contempt citations were a statement.

“The placement shortage crisis is so bad that Smith holds the dubious distinction of being the only director in DCFS’s history to be held in contempt of court a dozen times for failing to place children appropriately in violation of court orders,” Golbert said. “While the contempt findings were eventually either purged or reversed on appeal, they evidence the frustration of the parties in juvenile court, and apparently of the judges, in DCFS’s inability to find needed placements for its children.”

Smith repeatedly said during hearings and in media interviews that he was working hard to beef up specialized placements that were lost during the state’s two-year budget impasse between 2015 and 2017.

In addition to DCFS wards languishing in psychiatric placements, the agency’s Office of the Inspector General found in fiscal year 2023 that deaths of children who were involved with DCFS reached its highest number in 20 years. In 2023, the OIG reported that 171 children in Illinois died within a year of contact with the agency.

Among the children who died was 19-month-old Sophia Faye Davis of Springfield. Sophia died in February 2022 after child abuse allegations were made against her father’s girlfriend. A DCFS investigator found allegations were not credible, despite cuts to the child’s mouth, a black eye, bruises on her face and a broken arm just weeks before the child died from blunt force trauma. Cierra Coker, the woman accused of beating Sophia to death, remains in jail on first-degree murder charges. She is set to go to trial later this month.

A month before Sophia’s death, DCFS child protection investigator Deidre Silas was sent alone to a house to check on the welfare of six children. Sangamon County sheriff’s deputies found Silas’ body after she had been bludgeoned and stabbed to death. Critics pointed to high caseloads and short staffing as one contributor to Silas’ murder.

Pritzker, meanwhile, consistently backed Smith publicly amid the contempt citations and pressure from Republicans and others to fire him. On Wednesday, Smith expressed gratitude for the governor’s support.

“I thank him for the times that he’s had to stand in front of a microphone and defend me and our organization and his willingness to do that,” he said.

Uphill battle

Smith was one of Pritzker’s last key hires in 2019. When announcing Smith as acting director of DCFS in late March of that year, Pritzker’s office touted his years of experience working in Illinois’ child welfare system. Smith spent some of his early career at DCFS, and for a decade prior to his appointment as DCFS head, he oversaw foster care and intact family services for a decade at the state’s largest private child welfare service contractor, Aunt Martha’s.

Before officially appointing Smith the troubled agency’s 11th leader in less than eight years, Pritzker spent $50,000 of his own money to conduct a national search for a new director. Most of the previous 10 directors were stopgap appointees who held the role for less than a year under former Govs. Pat Quinn and Bruce Rauner.

The Senate didn’t vote to confirm Smith as DCFS director until June 2021, but when he leaves state service at the end of the year, he’ll have been the fourth-longest-tenured leader in the agency’s history going back to 1964.

Smith faced immediate challenges upon his appointment in the early months of Pritzker’s administration. The previous summer, ProPublica published an investigation detailing the circumstances that ultimately lead to Smith’s contempt citations – that Illinois foster children had been “languishing” in psychiatric hospitals, staying “beyond medical need” due to lack of appropriate placements being available.

Advocates, however, argued that situation worsened after Smith took over the agency and he also faced an onslaught of news reports that foster children sometimes slept in DCFS offices because there weren’t enough shelter beds available.

News outlets also reported that a DCFS contractor transported foster children in shackles during long car rides to and from placements. The agency subsequently banned the use of metal restraints, allowing only “soft” restraints in limited situations. But DCFS was forced to fire the company after it used shackles despite the ban, and in 2021 the General Assembly passed a law prohibiting their use.

In the months before Smith became DCFS director, the agency scrambled to deal with the fallout of a pair of high-profile child abuse and neglect deaths in central Illinois. In January 2019, eight-year-old Rica Rountree of Bloomington died from abuse inflicted on her by her father’s girlfriend, and in February of that year, the emaciated body of two-year-old Ta’Naja Barnes was found wrapped in a urine-soaked blanket in her family’s Decatur home. The day Smith was appointed, authorities say the parents of five-year-old AJ Freund of Crystal Lake beat the boy to death, though his body wouldn’t be found until more than a week later.

DCFS had previous involvement with all three families before the children’s deaths.

Smith also faced challenges implementing an inherited plan to transfer tens of thousands of foster children and former youth-in-care from traditional fee-for-service Medicaid to a managed care organization during his first year. The transition was ultimately delayed three times after media reporting and outcry from foster families showed the state had failed to recruit enough providers — including specialists — to care for that population, who often have complex medical needs.

Seven months into Smith’s tenure at the agency, a state audit found repeated failures at DCFS’s hotline for reporting child abuse and neglect, including that it sometimes took daysfor mandated reporters to get a call back from the agency.

COVID-19 exacerbates issues

Less than a year into Smith’s tenure, the COVID-19 pandemic hit Illinois, and the child welfare system was left scrambling. In addition to organizational chaos in those first few months, COVID set off a period of tension between the state and its myriad child welfare contractors that serve more than 80 percent of children and families in the system.

In the spring of 2021, a coalition of providers penned a scathing letter about Smith’s leadership as he awaited Senate confirmation.

“Ideally, a strong public-private partnership would leverage the best of both sectors for the benefit of the children and families they serve,” the letter said. “However, that relationship has eroded over time to the point now where providers say they feel disconnected and disrespected, segregated from decision-making and starved of resources and support.”

Since then, however, tensions have calmed between the state and providers, eased by an infusion of cash for provider reimbursements that had been held at the same levels for approximately two decades.

The chronically understaffed agency has also increased its headcount to its highest levels in the last 15 years, according to the governor’s office.

On Wednesday, Andrea Durbin, the CEO of the Illinois Collaboration on Youth, which sent the 2021 letter on behalf of service providers, praised DCFS’ response to the pandemic and the strides made during Smith’s tenure to recover from the budget impasse.

“Child welfare services are always a lagging indicator of the functionality of that system, and as predicted, the number of children and youth in care exploded following the impasse, putting an enormous strain on a system that had been neglected for nearly two decades,” Durbin said in a statement. “Thanks to the Governor and Director Smith, Illinois has seen five consecutive years of investments into the child welfare system to help it better cope with the growing population and the ongoing workforce crisis.”

Pritzker had reappointed Smith for another term in January, although his appointment was still pending in the Senate.

Smith left the all-staff call Wednesday with a charge to DCFS workers: “We are running and working at the highest level I believe that this agency has ever worked. Do not let anybody take that away from you. Because I’m sure as hell not letting them take it away from me.”