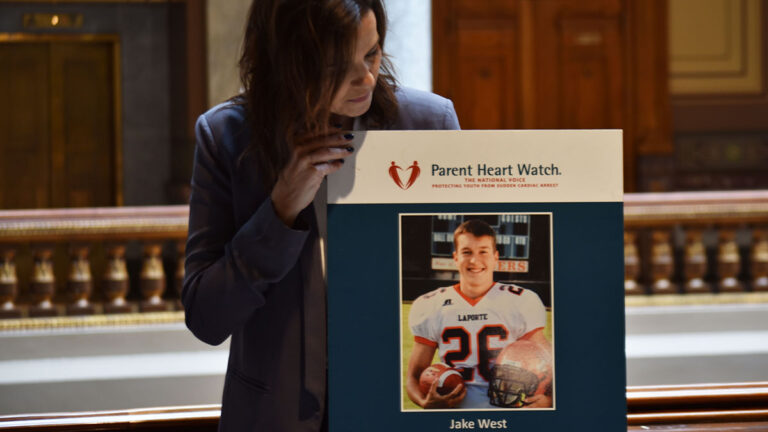

Jake West grew up in La Porte, Indiana, not far from Lake Michigan. His mother, Julie West, said he was always friendly to others.

“He was just kind and he brought other people in,” West said. “He was a type of kid that if someone wasn’t included, he was going to make sure that child was included. That’s just how he was, from the time he was little.”

As an athlete, he passed all of his physicals and he didn’t show signs of underlying heart problems. He was a healthy kid — until one day, he wasn’t.

When Jake was 17, he collapsed after running a play on the football field. School staff did CPR and student trainers jumped in to help out. But he died on the field in September 2013 from an undetected heart condition.

West wonders whether her son would still be alive if his school had a plan for the use of automated external defibrillators – more commonly known as AEDs – which send an electric shock to someone’s heart to help keep them alive.

Kentucky Governor Andy Beshear signed a bill into law in March requiring schools to keep portable AEDs in every middle and high school building and at school-sponsored events. At least eight other states, including Indiana, Missouri and Ohio, have introduced similar legislation mandating schools have emergency cardiac response plans, which may include access to AEDs and a plan to use them in response to incidents of sudden cardiac arrest.

West is advocating for Indiana’s AED bill, which would require all Indiana public, charter and private schools to make AEDs accessible at extracurricular activity practices and performances, including athletics, marching band and theater, since students have an increased risk of sudden cardiac arrest at these events.

“Every child should come home from school,” said West, the founder of the Play For Jake Foundation, which works to prevent sudden cardiac arrest deaths and provides heart screenings for youth. “They should not die at school. And so schools need to be prepared for that.”

But mandating these devices is a complicated decision.

A football player’s emergency sparks national conversation

West believes people are more aware of sudden cardiac arrest than ever before after millions of people saw the Buffalo Bill’s Damar Hamlin go into sudden cardiac arrest on live television earlier this year during an NFL game. Hamlin’s heartbeat was restored on the field using an AED.

But many school districts across the country are not privileged like Hamlin to have a team of medical professionals on the sidelines. Some don’t even have athletic trainers. And the longer someone takes to use life-saving devices, the greater the chance of them dying. A person’s chance of survival declines about 10 percent every minute defibrillation is delayed, according to the journal Sports Health.

Advocates for AED legislation say there is a way to help save these lives, at least while on school grounds — learning CPR, requiring an AED to be accessible during athletic practices and implementing an emergency cardiac response plan.

Getting more people trained in using AEDs is crucial, said Dr. Kristin Burns, a pediatric cardiologist with the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute.

“One of the most effective ways to get at this problem is to train children, young adults, bystanders — anyone who is around to feel comfortable jumping in and doing something and doing it quickly,” Burns said.

The machine guides users step by step, and provides written instructions for those who are hard of hearing, and verbal commands in different languages. Some AED advocates have said it’s so easy to use, anyone who can understand directions can operate the machine, including a child.

Should a potential liability outweigh saving a life?

More than 20 states currently have laws providing guidance for keeping AEDs and/or response plans on school grounds, or mandate them. Those requirements vary by state.

The chances of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest for children are low. Estimates for the number of U.S. children who experience out-of-hospital cardiac arrest each year range from 7,000 to more than 20,000. But such incidents can be fatal when they occur, with research showing survival rates as low as 11 percent.

Defibrillators cost roughly $1,000 to $3,000, and some schools may need more than one. Plus they have to purchase cabinets to store the device, carrying cases and other supplies to operate them. Then schools, with budgets and staffing already stretched thin due to COVID-19 pandemic labor shortages, must designate someone to take responsibility for these devices.

But those aren’t the only reasons that keep school districts from implementing AED protocols. It’s also the liability.

“People ask me all the time, ‘Should we get AEDs if we don't have to,’” said Richard Lazar, president of readiness systems with the AED Law Center. “And I mean, at a binary level it is, in most places, less risky to not have AEDs than it is to have AEDs.”

Recently, there have been multi-million lawsuits across the country after students died from cardiac arrest while on campus. In some cases, the facilities had AEDs, but failed to use them. And these scenarios could deter some school districts and lawmakers.

“What if they didn't have AEDs in the first place,” Lazar said. “Would they still be, you know, facing a lawsuit?”

A similar question was raised during an Indiana House Education Committee meeting in March. Chairman Rep. Bob Behning (R-Indianapolis) asked if a liability issue could be raised if a law is passed requiring schools to access an AED within three minutes, but someone is unable to do so within that time limit. The bill has since been amended to “establish a goal of responding within three minutes,” rather than requiring that specific response time.

That’s why AED advocates have been insistent that it’s not just about having the device on the premises. School districts would be required to have an emergency cardiac response plan so they know where a defibrillator is located and how to use it.

School districts across the country practice drills for fires, school shootings and inclement weather. Now advocates want the same preparation for sudden cardiac arrest and arrest deaths.

When Jake West died, there was an AED on campus. But it was in the coaches’ office and not easily accessible.

“I don't judge or blame anyone in Jake's situation, because we just didn't know any better,” West said. “But now we do.”

Indiana State Sen. Linda Rogers (R-Granger) introduced similar AED legislation last year, which passed unanimously out of the Senate Family and Children's committee, and the full Senate. But lawmakers ran out of time to hear the bill in the House education committee during the short session last spring. Now West is waiting to see if it will pass this year.

Initiating a cultural shift

In order to make a dent in the number of sudden cardiac arrests, advocates say there has to be a cultural shift around how communities respond to these events.

Although this legislation would require AEDs and emergency response plans in Indiana schools, it wouldn’t require them in other public places. Rogers said the devices are already in many other facilities, and the proposed bill is still a step in the right direction to prevent another young life from being taken from their family, friends and community.

For Martha Lopez-Anderson, preventing sudden cardiac arrest deaths has been her mission for roughly two decades.

“I was blindsided,” said Lopez-Anderson, advocacy director with Parent Heart Watch, a national organization that wants to end sudden cardiac arrest deaths in youth by 2030. “I thought I did everything right. My son had a well-child checkup 30 days before [he died]. And according to his pediatrician, everything was great. Well, clearly it wasn't.”

Lopez-Anderson’s 10-year-old son Sean died from sudden cardiac arrest in 2004 in Ocoee, Florida. She said there’s been an uptick in interest for AEDs and cardiac response plans since Hamlin went into cardiac arrest. But she’s noticed too many groups working in silos and not together.

Last week, The Smart Heart Sports Coalition was announced to provide $1 million for CPR education and AEDs. The new collaboration is between national athletic associations such as the NFL, NBA, MLB, NHL, NCAA, and national health organizations like the American Red Cross and the American Heart Association.

AED advocates like West want more education centers to become nationally recognized Project ADAM Heart Safe Schools — facilities that have implemented a sudden cardiac arrest plan, an AED, training, drills and an emergency response team.

Across the U.S., 4,129 schools were identified as “heart safe” e from 2004 through 2021, said Dr. Adam Kean, associate professor of clinical pediatrics at the Indiana University School of Medicine.

More schools likely qualify for this designation, he said, but they are working with a different organization or none at all.

Since beginning the Indiana program in 2020, only five schools have received the heart safe designation, out of the state’s roughly 1,800 public schools.

For now, West wants lawmakers to approve the bill before more lives are lost on school grounds.

“Without a doubt, lives will be saved,” West said. “Jake would still be here – my son would be 26 today here on Earth, not in heaven.”

Contact WFYI education reporter Elizabeth Gabriel at egabriel@wfyi.org. Follow on Twitter: @_elizabethgabs. This story comes from Side Effects Public Media — a health reporting collaboration based at WFYI in Indianapolis. We partner with NPR stations across the Midwest and surrounding areas, including Iowa Public Radio, WFPL in Kentucky, Ideastream Public Media in Ohio and KBIA and KCUR in Missouri.

9(MDM5MjE5NTg1MDE1Mjk1MTM5NjlkMzI1ZQ000))