The Clinton Power Station in DeWitt County south of Bloomington-Normal started operating in 1987. The nuclear plant is supposed to shut down in 2026, but owner Constellation Energy has applied for a 20-year license extension.

The aging plant is a massive assemblage of pipes, pumps, and valves. Security is rigorous. It takes about an hour to get through security. It’s easier to visit some state prisons.

Inside, there’s a stop at the office of the resident inspectors for the U.S. National Regulatory Commission [NRC]. That’s officially a small patch of federal land within the plant.

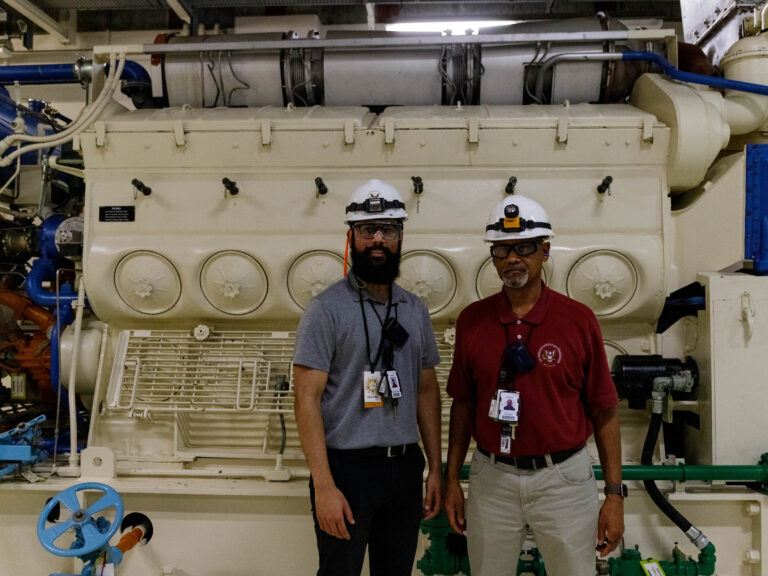

Jeffrey Steward is the senior resident inspector at Clinton. Arsalan Muneeruddin is the resident inspector. They go anywhere in the plant at any time to check on the facility, the equipment, and whether Constellation workers are doing things according to voluminous procedures and an equally robust Corrective Action Plan when there are hiccups.

After college at the University of Illinois, Muneeruddin spent about five years at commercial shipyards, but returned to nuclear engineering.

“I was just completely inspired and fascinated by the physics in how atoms interact,” said Muneeruddin.

Steward came out of the nuclear navy in submarines. He’s been an operator at a nuclear plant, but as an inspector, he’s on the other side looking over the shoulders of operators.

“It kind of speaks to my personality profile. I believe in doing the right thing in accordance with the procedures,” said Steward.

Every nuclear plant has resident inspectors from the NRC.

The tour begins

Steward and Muneeruddin took WGLT first to the radiation monitoring office that has a sign that lights up in cheery colors saying “Every Millirem Matters.” To go into the plant, everyone carries radiation monitors.

“These need to be up here on your lanyard. Their ED set points are eight millirem and 50 millirem,” said a desk worker. “No food, gum, candy, tobacco products like that in the RCA [reactor core area], so if you have anything to that effect go ahead and leave it here. I will keep it for you. Has anybody had any recent nuclear medicals, stress tests or anything like that? Nope? OK, you are all set with me.”

If everything works the way it’s supposed to, no one is exposed to anything much more than the background radiation everyone gets just living in Illinois.

“Put our hearing protection in and we’ll make our way inside the plant.”

We card through more turnstiles and walk past barrels of discarded gloves marked as waste and into the control building.

There are multiple secured doors needing card access. There are stairs up and stairs down. Way down. The offered hearing protection wasn’t just a kindness. It’s necessity. It’s noisy. But the kind of noise varies according to the purpose of the room.

From the hum of electrical equipment to turbine roar, you can almost tell which room you are in based on the noise profile.

The turbine building has a multi-story turbine of course and feed pumps. It’s sauna-level hot. The auxiliary building has emergency core cooling equipment. There’s a diesel generator that is the length of two train cars — a backup for the cooling pumps. There’s an air tank the size of one a farmer uses for a house propane supply; that’s just to help the engine start. A 45,000-gallon fuel tank to supply the diesel engine is in the basement.

“There are various buildings for various different purposes. And they are all intertwined together to make one beautiful plant,” said Muneeruddin.

There’s so much equipment there’s a need to color code things, even floor-to-ceiling pipes thicker than a person.

“Any piping you see that’s red will be dealing with fire protection. Blue is for cooling water. And those green configuration control areas, basically stay away from those areas because they are sensitive. So they have a little bit of buffer. Anything in orange is like Flex equipment,” said Muneeruddin.

Flex equipment? Muneeruddin said that’s a more recent addition prompted by the loss of external power that led to the nuclear disaster at Fukushima, Japan in 2011.

“Basically they lost all power at Fukushima and they had to deal with a flooding type of issue with their diesel generators being submerged under water because of the earthquake and the tsunami that occurred. Nationwide, we incorporated some regulations to help combat that accident,” said Muneeruddin.

Backing up the backup

Over and over, Steward and Muneeruddin talked about systems that are backups for other systems that are a backup. It is a bewildering recitation of defense-in-depth. They could be redundant, or they could be necessary.

A system to allow high pressure core cooling. Even one component is huge.

“One of the more important valves. You can see the size and the scale we’re talking about. These systems are designed to put high-pressured water into the core. Just the isolation valve itself, the size of it …You can get an idea how much water, how much force is required to stop that kind of flow,” said Muneeruddin.

Nuclear plants have to change out the fuel rods every so often. They come out hot, in a couple senses of the word: temperature and radiation. Workers temporarily store the used rods in a very deep pool of water in yet another room of the plant.

From a couple stories up you can see in one corner of the pool there are some bundles that glow blue. That’s called Cherenkov radiation. As electrons come sleeting off the fuel, they hit the water travelling faster than light is supposed to go in water. The visual effect is similar to the sonic boom a jet creates by going faster than the speed of sound in air. There will be more of a glow next month when the plant shuts down for a few weeks to refuel.

There’s a requirement for a certain level of water above the top of the spent fuel bundles.

“As the water level goes down the cooling is reduced and so the amount of radiation shielding that you get from the water is reduced as well,” said Steward.

The water is refreshed and changed out through the “fuel pool cooling and cleanup system,” he said.

“There are two pumps, a couple heat exchangers, some demineralizers that maintain the chemistry of this water. Alkalinity, suspended solids, that kind of thing is monitored by chemistry,” said Steward.

Once the spent fuel rods cool some, they’re supposed to go to a federal nuclear waste repository. After decades of dealing with a political hot potato of where that facility would go, there still isn’t one. The last attempt to create a repository under Yucca Mountain Nevada died during the Obama administration. So, the bundles are packed in casks and stored on site.

Steward and Muneeruddin can go anywhere in the plant at any time. They try to cover every room over a couple weeks. They do drop-ins on the overnight shift. And when something unusual happens, they hustle.

“Getting the call in the middle of the night is both stressful and exciting at the same time, especially when you have to come in. Whenever an event occurs, that is both an opportunity and a time of learning, cause chances are you have never seen this before,” said Muneeruddin.

The last time that happened was in January. A fault on a power source outside the plant caused a circuit breaker to trip on the main turbine and the reactor to SCRAM, or abruptly shut down.

“The turbine had nowhere to put output power because both the output breakers were opened up,” said Muneeruddin. “Normally, one of those two output breakers would stay closed and the power generated would have a route to go outside. But the fact both of them opened up caused there to be a power load imbalance and therefore, the reactor to SCRAM.”

At first, all the inspectors knew was the reactor had shut down. They asked questions. Details emerged. The Ameren utility started investigating its transmission lines. Turns out the fault happened 17 miles away — not at the plant owned by Constellation Energy.

It’s the detective work that turns on Muneeruddin. He said normally issues won’t be simple. You are constantly being challenged.

“I did my engineering in nuclear, but you wish you had an electrical engineering degree one day, the next day you wish you had a mechanical engineering degree, then you want to be a chemical engineer another day. You are basically trying to be cross functional, and that’s where a lot of your learning comes in. That’s the beauty of this job,” said Muneeruddin.

Part of the challenge is assessing the state of the aging plant. Some pipes corrode or thin. Older equipment can fail. Steward said they are getting away from analog and to digital controls for the main turbine, feed water, electro hydrological controls, and so on.

“These plants are being operated in a lot of cases extended beyond their original 40-year licenses, going into plant extensions. It’s good to see things are being updated continually, as they grow aged,” said Steward.

There’s a limit to changes, though. The Nuclear Regulatory Commission operating license for the Clinton plant has to be amended with each substantive alteration. They don’t want to mess too much with the holistic structure of the plant.

Clinton’s safety record

The Clinton plant has a pretty good safety record. A review of several years of inspection reports shows a few low-level “green” or non-critical system problems. There was one security-related glitch in 2021. The NRC isn’t saying what that was. The last time there was a greater than “green” finding by inspectors was five years ago. Even that was what they call a white-level violation, not the more serious yellow or red designations.

And Muneeruddin said the resident inspectors are well aware of the need to maintain a professional distance that could influence their findings.

“We are part of the community and at the same time we still have to maintain our objectivity. Be friendly with the site employees, but you can’t be friends. And that extends to outside of work as well. I can’t go home and take them out to dinner or go to someone’s house,” said Muneeruddin.

Constellation Energy’s application for a license extension went to the NRC last October. It’ll take about two years for the commission to decide whether to grant the request.

Meanwhile, federal resident inspectors Jeff Steward and Arsalan Muneeruddin will continue working to keep the plant as safe as it is secure.

9(MDM5MjE5NTg1MDE1Mjk1MTM5NjlkMzI1ZQ000))