NORMAL – Tracy Freeman heard from a former student earlier this year. Freeman, who teaches social studies at Normal West Community High School in central Illinois, says the student had traveled to Washington D.C. to participate in the Trump rally on January 6. The former student said they didn’t go into the U. S. Capitol building, but saw things that were disturbing and wanted to talk.

Listen to the audio story here:

“I think that many times a student who is expressing or sharing with me some of their beliefs that might be more extreme, number one, they’re sharing them with me. So, to me, that tells me they’re questioning it a little bit,” she says.

Freeman didn’t criticize the student or tell them they’d done anything wrong. Instead, she asked them to reflect on what they had learned in her class about charismatic leaders, and why blind loyalty to anything or anyone is a problem.

“My goal was not to make him not be a Trump fan, my goal was to get him to critically think about being in a situation out of loyalty to a person that could have ended up very badly for him,” Freeman says.

Freeman has shifted the way she teaches over the last decade, thanks in part to professional development provided by the Robert R. McCormick Foundation and other groups after Illinois updated its civics standards in 2015. She now focuses on training her students to challenge their assumptions and remain open to other perspectives.

A deeply divided country makes it harder for social studies teachers like Freeman to do their jobs. While politics has always been a tricky subject to tackle in the classroom, educators say it’s essential now for students to understand how to talk to someone they disagree with. The pandemic, with its remote learning and hybrid instruction, has made already difficult classroom conversations even more challenging.

Diana Hess, dean of the school of education at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, says it’s necessary to provide students a non-partisan civics education that prepares them for a highly partisan world. Hess has studied how middle and high school aged students learn about highly controversial political issues.

“Even though we’ve seen times in American society when there’s been deep political divisions, I think this level of political polarization is different than anything that we’ve faced before,” Hess says. “And because of that, I think it is much more challenging to teach civics now than it has been in the past. But it’s also, I would argue, much more necessary.”

She says schools aren’t to blame for political polarization — but they could be a part of the solution. The key, she says, is teaching students how to talk to and respect the political views of those they disagree with. Hess says the “jury is still out” on whether a high quality civic education can mitigate political polarization, but what her research shows is promising.

“I think what we want to help young people do — and adults for that matter — is to learn how to talk with people who have different views in a way where we don’t demonize difference,” Hess says. “And I do think, overall, we will find that if, you know, lots and lots of young people are taught how to do that, that that should, at some point, begin to have an effect on political polarization.”

But Hess cautions that not all views deserve respect, like those based on misinformation or racist ideology. She says educators also need to teach students how to become critical consumers of information.

“We need to very explicitly teach young people how to assess the veracity of information,” Hess says. She adds that a great civics teacher needs to be able to help students deal productively with their differences of opinion, while also sending a clear message about justice, diversity, equity and inclusion.

“There are many, many teachers who are dealing with this really well,” Hess says. “I know those teachers, and I’ve been in their classrooms, and I’ve talked to their students… so I know it can really make a difference.”

‘Being a good citizen’

Mariah May loves her civics class. The 17-year-old senior at Belleville East High School in southern Illinois, about 30 minutes east of St. Louis, says her civics education has inspired her to become a trial lawyer.

But May is dismayed by the polarization in her community and in her school. She says students were divided over the last presidential election, and they shamed and shunned people who didn’t support the candidate they preferred.

May says she thinks it’s better to talk respectfully about political differences and try to understand why people believe or feel the way that they do. For example, May says she recently discussed immigration policy with someone who identifies as Republican. She says they both want to stop illegal immigration.

“But I was trying to emphasize how we can’t just disregard human rights,” May says. “But I also need to understand where he’s coming from, in addition to trying to emphasize my point as well so that way we can reach a common ground… and understand each other.”

May’s classmate, Andrew Harrill, also a 17-year-old senior, has had similar experiences. He says his civics education has helped him talk to people on the other side of the political spectrum, and taught him that “being a good citizen is respecting others, even when you don’t necessarily respect their views.”

“One of my friends from school is more to the left, and I tend to go the other way,” Harrill says. “But one thing we value a lot is talking about our differences and possible solutions that can involve both points of view.”

Like May, Harrill is worried about the polarizing discourse, particularly social media exchanges where people don’t actually talk to each other, they just trade insults.

“And if there’s no consequence for it, and if there’s no push to communicate in a friendly or respectful way, then it will just drive our country further apart. And that’s how a democracy will fall,” he says.

May says the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated these divisions.

“Because a lot of people have become comfortable going online to express how they feel, and they become less likely to address situations how they would online in person,” she says. “And I feel like we need to normalize having these discussions, while also being respectful of other people’s opinions.”

‘The future lies with them’

Kelly Keogh agrees the pandemic has made engaging students in tough conversations much harder. Keogh is a social studies teacher at Normal Community High School, across town from where Freeman teaches in McLean County. The school is operating on a hybrid model, meaning some students show up for classes and others learn remotely.

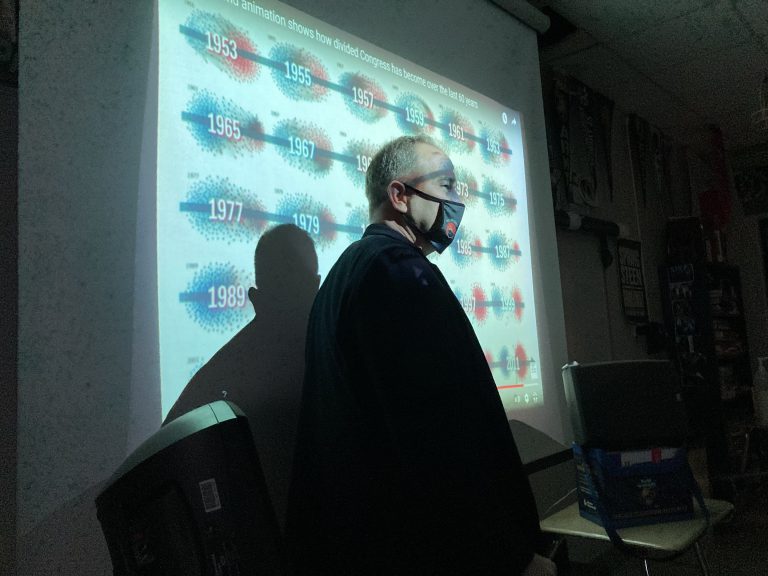

In a recent Advanced Placement government class, Keogh instructed students attending virtually to work together on a separate assignment, while he led the in-person class of about 10 students, all in masks, in a discussion about polarization in American politics.

Keogh says he can’t force students participating virtually to turn their cameras on, which means he has no idea what some of his full-time remote students look like.

“It’s almost impossible to have effective discussions, especially on controversial issues, when you’re not having any eye contact,” Keogh says. Even the masks are a hindrance, because they make it difficult to interpret facial expressions, he says.

Keogh says even before the pandemic, engaging students in difficult discussions about political differences was harder in recent years, especially as polarization seeped into the classroom. For example, he says students at one point could choose icons in their virtual classrooms. He says some students chose “Black Lives Matter” icons while others chose “Blue Lives Matter” icons, a move that upset both liberal and conservative parents. As a result, Keogh says the school no longer allows students to select their own icons.

“That [shows] how polarized things have gotten, that even an icon can elicit a certain amount of division,” he says.

Additionally, adults aren’t modeling the behavior teachers like Keogh and Freeman are trying to instill in students.

“You can turn on the talk shows and have people screaming past each other over whatever issue it is, even as simple as wearing a mask,” Keogh says. But there are some issues, like racism, where Keogh has to make it clear to his students that there is a right and a wrong.

“Sometimes when you hear stuff you, as a person, have to take a stance, (and) say that’s not okay,” he says.

Despite the pandemic and current social and political divisions, Keogh says he’s committed to fostering respectful conversations among students about their differences. Students in one of his classes recently debated what the U.S. role in the Middle East should be in the future. Students were assigned to four different viewpoints and debated each other on the merits of their positions. Afterward, he asked students to share their own perspectives on the issue.

“What it facilitates is they now have not just a background knowledge, but they now can see from a different viewpoint where somebody might think differently, and can take that into consideration,” he says.

Keogh strongly believes that teaching students to engage respectfully with people who don’t share their views can eventually lead to decreased political polarization. And he looks at the future with a mixture of deep concern and hope. He says his students are bright, and his younger colleagues are committed to teaching young people how to think critically and engage civilly.

“The future lies with them,” Keogh says. “So it gives me some faith.”

Lee Gaines is a reporter for Illinois Public Media.

Follow Lee Gaines on Twitter: @LeeVGaines