In one town in the Metro East, across the Mississippi River from St. Louis, police are forcing landlords to evict tenants who have called for help during an overdose because they have heroin or other controlled substances in their rental property.

Police in Granite City – a town of around 30,000 residents – are using a crime-free housing ordinance the city adopted in 2010, which supporters say makes neighborhoods safer and reduces crime. About a third of the residents there are renters.

The ordinance requires landlords to evict tenants who are arrested or suspected of crimes, such as drug possession, or repeatedly violate a number of city ordinances, such as littering or letting the grass grow too long. Landlords can face fines or lose their rental license if they do not.

Over the past five years, Granite City police have sent at least 300 notices to landlords to evict tenants because of violations of the crime-free housing ordinance, according to an Illinois Newsroom analysis of police records obtained through a Freedom Of Information Act request. Of those, 28 were the result of a call for help during an overdose.

The crime-free officer for the Granite City Police Department declined on behalf of the department to be interviewed for this article, saying the program is proven and speaks for itself. The Granite City mayor did not return several requests for an interview.

Dozens of Illinois communities have similar rules. Neighboring Alton, a town of nearly 28,000 residents, and Rantoul, a town of about 13,000 residents located in Central Illinois, just started their own crime-free housing programs.

Public health advocates and those in recovery from addiction say the rules put people with addictions at risk. Meanwhile, civil liberty groups raise concerns about punishing people for seeking help during emergencies.

Madison County, home to Granite City, saw 109 opioid-related deaths in 2018, topping the last record-setting year in 2014 when 91 people died from opioids .

Since 2012, under a state law known as a “Good Samaritan” law, Illinois police have not been allowed to arrest people for drug possession who call 911 for drug to report an overdose.

‘Moves The Problem Around’

Lewis Simpson is a full-time landlord, managing several rental properties in Granite City. On a recent weekday, he was cleaning out an apartment the tenants abandoned after skipping rent for a month and having police look for one of the tenants on suspicion of shoplifting.

Days later, Simpson got a letter from police saying there was a warrant out for the tenant’s arrest for shoplifting and he had to evict them. He said he was already trying to serve them an eviction notice when they left.

Clothes, baby toys and furniture were strewn about the two-bedroom apartment, which Simpson rents for $475 a month. In a dresser drawer, he found dozens of empty pill capsules, a sign at least one likely was abusing opioids.

“This is what we’re facing as landlords,” he said. “This is what the police are facing.”

He got a crime-free violation notice for a different tenant who had called to report an overdose in January of 2017. He said the tenant hadn’t been paying rent, and he had already started paperwork to evict her. She moved out before he had to.

He said in his experience, most people getting cited for crime-free violations are not paying rent and he would have to evict them anyway.

“If the police had a better way of doing stuff, I’m sure they would,” he said. “They’re struggling. The neighborhoods are struggling. And so far this is what they found to help them out.”

Still, that doesn’t make him a supporter. He points out that the way the crime-free rules are written, a tenant he kicks out can just go rent the place across the street.

“It’s a wash, it gets them down the road to somewhere else,” he said. “It reduces crime because they’re not stealing from the neighbor here. They’re somewhere else stealing stuff. It moves the problem around.”

Appeals

Under Granite City’s Crime-Free Multi-Housing Ordinance, the police department sent 27 letters over the last five years to landlords instructing them to evict tenants because, while responding to emergency calls, police saw illegal drugs or drug paraphernalia.

They say that violates their crime-free lease addendum – a mandatory addition to every lease in Granite City tenants sign promising they won’t break the law or violate the city’s ordinances.

Most tenants cited as a result of an overdose call moved out, even though there was no eviction case filed with Madison County Circuit Court. In four cases, there was an eviction case filed. The crime-free officer and two landlords Illinois Newsroom talked to confirmed that if there is no eviction case filed, the likely outcome was that the landlord and tenant reached an agreement for the tenant to leave.

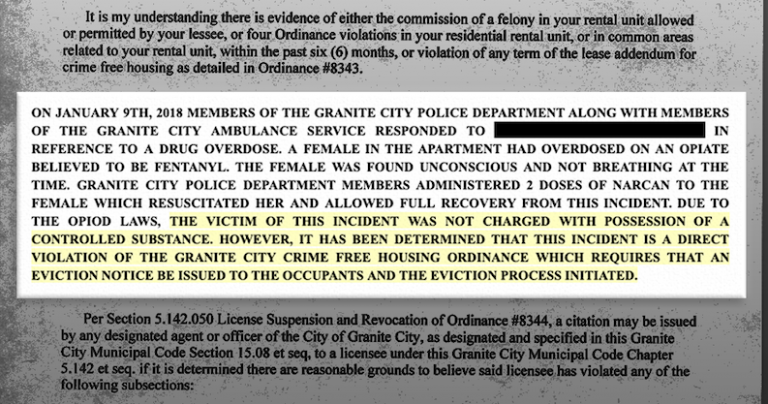

In a few of the letters, obtained through a freedom of information request, police officers acknowledged they can’t arrest the tenant for having drugs:

“Due to Illinois law, [Redacted] cannot be formally charged with possession of a controlled substance due to the medical emergency.”

The letters, sent to both tenants and landlords, instruct landlords to begin eviction proceedings.

Both tenants and landlords have 15 days to appeal the violation to the Granite City Building and Zoning Office, and can have hearing before a city hearing officer, who is appointed by the mayor.

Scott Green, a Granite City property manager, said a few years ago, he appealed on behalf of a tenant who he was instructed to evict after an overdose call.

“Well, if he’s been paying his rent on time, what if I don’t want to evict him?” he said he argued to the city. “At that time, he was in recovery and trying to get better.”

Like Simpson, Green thinks the rules are ineffective because anyone who is evicted, can rent right next door. More frustrating for Green is that he feels like the city puts him in the middle.

“The city seems to make me the bad guy,” he said. “If I don’t cooperate, they threaten to not allow me to get my occupancy permits for the next tenants.”

The city eventually agreed Green didn’t have to force his tenant out then. But Green evicted him later for not paying rent.

Of the letters sent as a result of overdose calls, eight tenants appealed the crime-free violation, records obtained by Illinois Newsroom show. Two had their violations overturned by the hearing officer.

In one appeal letter, a man pleads with the city to allow him to stay in apartment, where a few days earlier the mother of his child, who was in recovery, relapse and overdosed. “At this point in time, I cannot afford to take my 6-month-old daughter in the middle of winter and have no place to stay,” he wrote. Their case was not ruled on by the hearing officer.

Stigma Around Addiction

Brent Cummins, director of adult substance use services at Chestnut Health Systems in Granite City, worries about what happens after tenants lose their homes.

“Somebody who’s in the midst of an addiction they’re not able to manage, to control what’s going on with him or herself,” he said. “Unfortunately, it’s going to make the situation worse.”

Overdoses continue to climb and the opioid crisis is getting worse. But they are trying new approaches, particularly when it comes to working with police. Chestnut Health has a peer recovery specialist, an employee who’s in recovery from addiction who the police or others can call to connect people with addictions to different treatment services.

“We’ve done more and more in the past couple years to try to engage the police on that kind of level, and provide them with some more tools to handle these situations,” he said.

The crime-free rules in Granite City, though, Cummins said he sees those as a short-term solution that could cause a much bigger problem.

“Is there a more strategic opportunity for us to intervene and handle it and keep people intact and keep the situation from escalating to bigger problem?” he asked.

Sandra Park is a senior attorney with the ACLU Women’s Rights Project and has been involved in lawsuits against cities over their crime-free and nuisance ordinances. Her primary concern is that the rules discourage people from seeking help.

“If you tell communities that calling for emergency assistance in that situation, it could lead to eviction, you’re essentially telling them to stop calling even in dire circumstances where someone may need life-saving, medical help,” she said.

A study in Ohio shows Granite City is not the only place residents could lose their housing after calling for help during an overdose. Researchers with Cleveland State University looked at how four cities outside of Cleveland – Bedford, Euclid, Lakewood, and Parma – determined which properties and tenants were nuisances, a designation which could result in eviction. They found that, depending on the city, 10 percent to 40 percent of the designations were because of a call for help during an overdose.

In Iowa, California and Pennsylvania, Park said the ACLU has pushed for laws that would protect anyone making emergency service calls from these types of rules.

Joe Perry – a recovery coach at a few halfway houses in Granite City – said he doesn’t think people are avoiding calling 911 out of fear of being evicted.

While Perry, who is in recovery himself, said he found a strong community in Granite City, he also said he hopes police would offer more connections to treatment and other services.

But he said the use of the crime-free housing rules shows a stigma around addiction.

“Instead of offering treatment, or somebody stepping up and saying, ‘Hey, we have these services available.’ Instead, they just put them out to the curb,” he said. “It’s the stigma that comes with it, you know, you’re using drugs, we don’t want you in our community.”