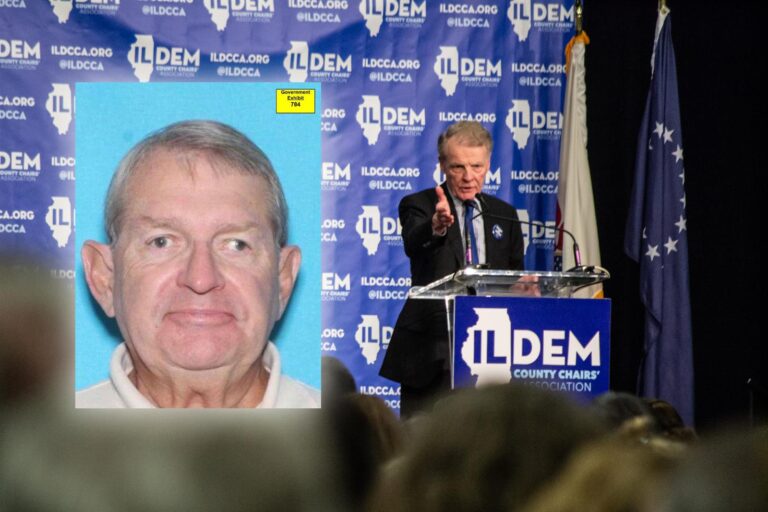

CHICAGO – In fall 2018, longtime former State Rep. Lou Lang, D-Skokie, received a phone call from Mike McClain, who had spent decades lobbying for electric utility Commonwealth Edison after 10 years in the General Assembly.

McClain was delivering a message from House Speaker Michael Madigan, who was worried Lang was becoming a liability to his Democratic caucus – a liability the now-former speaker would rather not deal with after the year he’d already had.

Earlier in 2018, a former campaign staffer publicly accused Madigan of failing to address her complaints of sexual harassment by her colleague in the speaker’s political organization. And a few months later, Madigan was forced to axe his longtime chief of staff over his alleged harassment of subordinates.

Read more: One year after Madigan’s indictment, former speaker’s allies prepare for trial

Lang had already been publicly accused of harassment and bullying in May of that year, although the allegations proved thin. Lang came out of the experience mostly unscathed, hoping for a quick comeback after giving up his House leadership position – a face-saving move he expected to be only temporary.

But McClain called Lang with some bad news: Another woman was threatening to come forward with harassment allegations if Lang was reinstated to a leadership position. What’s more, Madigan wanted Lang to resign from office to become a lobbyist.

“So this is no longer me talking,” McClain said in that Nov. 2018 call. “I’m an agent of somebody that cares deeply about you, who thinks that you really oughta move on.”

“Agent,” as used by McClain, is exactly how federal prosecutors want the jury to think of the defendant in the trial where he and three others stand accused of bribing Madigan with jobs and contracts for the speaker’s political allies in exchange for legislation favorable – and lucrative – to ComEd.

Read more: Madigan looms large in trial of ex-ComEd lobbyists, exec

Government lawyers played several other recordings of calls from McClain’s cell phone that they had wiretapped in 2018 and 2019. They included a call where his directives from Madigan were confirmed by the speaker himself.

“You know, I think the guy’s going to be a continuing problem, that’s my expectation,” Madigan said of Lang. “And I mean, you can understand my position, right? I have to sit and think…do I appoint him to the leadership or not?”

In federal court Thursday, Lang testified that after McClain’s call and a subsequent meeting with Madigan, he understood that he’d never achieve his ultimate ambition in his legislative career: rising from third-most senior leader in the House to deputy majority leader and eventually House speaker.

“It was very clear to me that there had been a decision made by the speaker that I was not going to move up in the ranks, and the reputation I had built over 32 years was not going to avail me to much progress in my career,” Lang said Thursday during government questioning.

During cross-examination, McClain attorney Pat Cotter said it was understandable that Madigan wouldn’t want “someone in leadership who was at that point facing a second sexual harassment claim.”

But Lang declined to acknowledge he was facing harassment claims at the time, employing the line “just because someone says there was an allegation does not make it true.” He especially chafed at Cotter’s later use of the word “charges.”

“I was not facing sexual harassment charges,” Lang said testily. “And I’ll tell you right here in federal court that I resent the allegation and the inference.”

Calls between Madigan and McClain mentioned they’d been informed of the harassment claims against Lang by the former top attorney in the speaker’s office at the time, Heather Wier Vaught. Wier Vaught on Thursday confirmed the existence of those 2018-era harassment claims surrounding Lang.

“I don’t dispute that more than one person came forward with allegations against Lou,” she told Capitol News Illinois, noting those individuals whose claims never were made public had a right to privacy.

Lang eventually resigned from the House in January 2019, shortly before taking the oath of office in what would have been his 17th term in the legislature. He immediately began lobbying his former colleagues – a long-common practice in Springfield.

Cotter did get some favorable testimony out of Lang when he affirmed that he was not “punished” by Madigan because he didn’t vote for ComEd’s signature legislation in 2011. He also said he never saw Madigan do “anything special” to ensure that bill or the utility’s two other major legislative priorities pass in 2013 and 2016.

“In my entire 32-year career, Mike Madigan never ordered me to do anything,” Lang said of his experience with the speaker.

In playing other snippets of McClain’s calls, the government sought to discredit the arguments made in the defense’s opening statements the day prior, in which Cotter said McClain’s and Madigan’s close relationship wasn’t evidence of any conspiracy.

“Do you call your friends for advice?” Cotter asked the jury Wednesday. “Do you call your friends at work? When you do that, are you entering a conspiracy or is that friendship? I’d argue it’s the very nature of friendship.”

Over a handful of recordings, the government let McClain’s words speak for themselves as the former lobbyist explained who his true client was.

“I finally came to peace with that maybe 20 years ago when I convinced myself that my client is the speaker,” McClain said in a call to a top staffer in Madigan’s office, who said he was struggling with always making decisions with Madigan’s best interest in mind.

“My client is not ComEd, my client is not (the Chicago Board Options Exchange), my client is not Walgreens, my client is the speaker,” McClain said in the call. “…If that’s the way you think, if that’s the way you frame your talking points, (Madigan will) never second-guess you.”

Other recordings included McClain referring to an increase in “assignments” given to him by Madigan after his official retirement as ComEd’s top contract lobbyist in 2016. McClain thereafter became a consultant for the utility instead.

Earlier on Thursday, the jury heard testimony from former State Reps. Carol Sente, D-Vernon Hills, and Scott Drury, D-Highwood, both of whom said they were punished by Madigan when they refused to go along with their Democratic colleagues. Drury had refused to vote for Madigan when he ran for a 17th term as House speaker in 2017, an intra-caucus vote that for most of Madigan’s career had been both unanimous and a foregone conclusion.

Drury has loudly – and sometimes proudly – complained that after his refusal to vote for Madigan the speaker declined to send him a custom engraved clock given to all the other members of his caucus commemorating Madigan’s tenure. Neither prosecutors nor defense attorneys asked Drury about that episode on Thursday, but Drury testified that he’d not been given any sort of committee chair assignment and none of his bills passed during that two-year term.

Sente testified that she believed a committee chairmanship role – which included a stipend – was taken away from her in 2015 as punishment for things like pushing for term limits on legislative leaders and voting against a Madigan-proposed constitutional amendment to allow a “millionaires’ tax.”

After Sente agreed with Cotter’s question that it was “reasonable” for members of the Democratic caucus to vote with generally Democratic policies, he asked if it was “reasonable for there to be consequences for members who don’t go along with their party.”

“I’m not sure I agree with that,” Sente said.

Cotter pointed out that Sente’s committee chair job was restored 10 months later.

“This is all politics, isn’t it Ms. Sente?” Cotter asked.

“So I learned,” Sente said.

Trial will resume at 10 a.m. on Monday.