URBANA – One hundred years ago, on the evening of Thursday, April 6, 1922, the University of Illinois’ radio station went on the air for its first broadcast at 833 kilohertz (the station moved to 1100 kHz in 1924). WRM, the service that would become WILL Radio, was cutting-edge technology in 1922. Americans were still figuring out what role radio broadcasting would play in their lives.

The student newspaper, the Daily Illini, reported on that first broadcast, with a front-page article, headlined “Radio Service Spreads News of University.”

What Listeners Heard In An Inaugural Broadcast

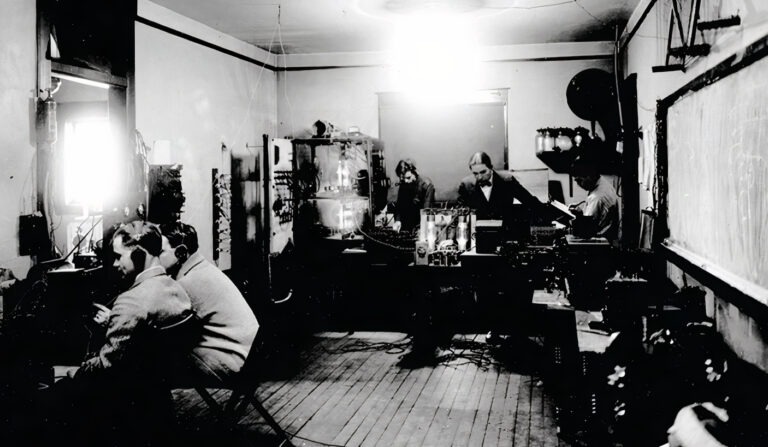

“With the simplicity of talking into a telephone mouthpiece”, the article read, “Dean Thomas Arkle Clark, Josef F. Wright, director of publicity; Carl Stephens, secretary and treasurer of the alumni association, and F.A. Brown of the department of electrical engineering, inaugurated the radio broadcasting service of the University last night at the electrical engineering laboratory.”

Dean Clark’s talk, on “Why College Students Fail,” was followed by other short talks by university faculty on dairy science and park development, as well as news about the U of I’s track and baseball teams, construction of the new Memorial Stadium, and a few jokes thrown in for good measure.

According to the newspaper report, Josef Wright, who would become the radio station’s first director, asked listeners to write in with reports on reception, and what they would like to hear in future broadcasts.

The Daily Illini reported that university president David Kinley would speak on a future program. Topics for other talks being planned would range from business law to new football rules.

The University of Illinois’ first official radio broadcast was a brief one: fifteen minutes of programming, followed by fifteen minutes of silence, and then, programming for another fifteen minutes. But WRM was back on the air the following Thursday evening. According to the Daily Illini, the station’s second broadcast included its first musical program: highlights from “Teatime In Tibet,” an original operetta composed and performed by university students.

University of IllinoisSoon, the campus auditorium (called Foellinger Auditorium today) was wired for radio, and WRM was bringing its listeners live concerts by student musical groups such as the Varsity Men’s Glee Club.

WRM broadcast its first Illini football game in 1923, and game broadcasts would be a regular feature of the station up into the 1970s.

But all in all, the station’s output was modest at first, broadcasting just one evening a week (increased to twice a week in September 1922) with a focus on faculty lectures and student and faculty musical performances. University of Illinois trustees made it clear that they wanted to provide an educational service. University President David Kinley wasn’t ready to spend a lot of money on radio. And he complained in a letter to university board trustee Merle Trees (later the board president) about the extra work WRM was creating.

“They seem to think that we people here are not busy, and have leisure enough to be putting on programs, giving lectures, et cetera, for broadcasting,” wrote Kinley (pictured above). “I cannot myself see that there is any advantage in its excepting what might be credited to ‘advertising.’”

But University of Michigan media historian Susan Douglas says others in the academic realm saw radio as a new way to educate America.

“Radio was accompanied by a host of utopian predictions,” said Douglas, “about educating people, about uplifting the illiterate, about radio becoming a giant university, you know, in the sky, where people could hear lectures that they could never hear in person, because they were too far away, or they didn’t have the money to go to school.

The Daily Illini was among those early optimists. After WRM’s first broadcast, an editorial in the student newspaper predicted that the station would help deepen old college ties for U of I alumni.

“Through the newly-licensed radio broadcasting station here, the University will gain one distinct and outstanding advantage — a better informed alumni,” the D-I editorial argued. “Conveying the sounds of university life will give a much more personal touch than the cold, blank type of newspaper and magazine correspondents.”

As it entered its second decade, WRM was broadcasting on a daily schedule, from its own building located on Wright Street near the old Illinois Field on the University of Illinois campus. A wealthy donor, Boetius H. Sullivan, paid for the building and its broadcasting equipment, in memory of his late father, Illinois Democratic party leader Roger C. Sullivan (the building, no longer standing, was named the Roger C. Sullivan Memorial Station).

New Regulatory Challenges

But even as it gained a new home and new equipment, the University of Illinois station faced challenges, as federal regulators worked to clear out interference on the AM radio band, due to too many stations trying to fit into limited spectrum space. There were few alternatives for broadcasters; FM, TV and the internet were not yet options. So, the newly formed Federal Radio Commission started deciding which stations could broadcast on what frequencies, at what times, and with how much power.

U of I professor emeritus and media scholar Robert W. McChesney examined this period of American broadcasting in his book, Telecommunications, Mass Media, and Democracy: The Battle for the Control of U.S. Broadcasting, 1928-1935. He says the process of bringing order to airwaves produced winners and losers, with commercial radio and the new radio networks on the winning side, and noncommercial stations like WILL losing out.

“For the rest of the stations, including all the educational stations,” said McChesney, “they were put at lower power on signals where they had to share the signal with other stations in their community, including WILL. They didn’t get the thing for the entire amount of time, they got it for a portion of the time. And then like maybe a station owned by a business would get six hours one day on the same slot.”

Newspaper reports in 1928 announced WRM’s reassignment to various frequencies. It eventually ended up at 890 kilohertz (now used by clear channel station WLS in Chicago). The station now operated on a timeshare basis, taking turns broadcasting with radio stations in South Dakota and Iowa. WRM was limited to 90 minutes of programming a day, and its transmitter power was limited.

The Daily Illini noted the new limits placed on the station in an editorial, but it said station director Josef Wright had been successful overall in his year-long negotiations with the FRC to keep the station on the air.

“As a result of these negotiations he was able to keep WRM running, though many Illinois stations will be closed,” the newspaper stated.

Soon after that editorial was published, WRM was assigned the call letters it had requested a few years earlier, and still has today: WILL.

But WILL’s ability to reach an audience was limited, compared to that evening in 1922 when the station first signed on as WRM. In those first days, WRM’s signal could travel at night for hundreds of miles. Wright was frustrated by the new restrictions on the station’s hours and transmitter output, as he would later express in a letter.

“Those of us responsible for the direction of station WILL at various times seriously contemplated retirement from the broadcasting game,” lamented Wright. “This is due solely to the fact that our power limitations so restricted our audience that we felt that we could not justify the expenditure of tax money to go ahead with the work, even though the total yearly cost of operating the station is absurdly low.”

WILL Comes Into Its Own

In 1935, WILL gained some much-needed stability. The Federal Communications Commission assigned the station to 580 AM, classified as a regional broadcast frequency, and the one the station uses today. The station’s transmitter power was limited at first to 1,000 watts, but was later raised to its current level of 5,000 watts. WILL’s timesharing requirement was relaxed. The station had to sign off at sunset, to protect the nighttime signal of another station, WIBW in Topeka, Kansas. But it could broadcast all day, with a signal that reached most of Illinois. (Today, WILL-AM is also allowed to broadcast after sundown at low power.)

By this time, radio broadcasting in the U.S. had grown from a high-tech hobby into a widely used medium. And it was one that was firmly established as advertiser-supported , devoted mostly to light entertainment. Stars such as Rudy Vallee, Fred Allen, Paul Whiteman and Major Bowes hosted some of the top-rated shows of the time on the commercial radio networks, Columbia, NBC and the new Mutual system. But WILL was on the air as well, one of just a few dozen educational radio stations that survived from the radio craze of the 1920s into the 1930s.

From its first broadcast as WRM on April 6, 1922, into the coming decades, WILL would build a program schedule dedicated to both learning and culture, eventually expanding its content to FM, television and online. And it would reach out to other educational broadcasters, bringing them together at conferences, and playing a vital role in program distribution. WILL’s efforts would help pave the way for today’s nationwide system of public broadcasting.

For another account of WILL-AM’s early years, read this article by Katie Buzard in the WILL100 section of the WILL website.