When José moved his family to the U.S. from Mexico nearly two decades ago, he had hopes of giving his children a better life.

But now he worries for the future of his 21-year-old-son, who was diagnosed with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder last year.

José said his son was a happy child who loved playing with friends. But in recent years, there was a stark change—his son started acting aggressively, talked about hearing voices and struggled with suicidal thoughts.

José and his son live in Illinois. They are undocumented, so he asked to be identified only by his middle name. Through an interpreter, José recalled, “He asked us for help, but we didn’t know how to help him. He’d say, ‘Dad, I feel like I’m going crazy.’”

Last year, his son was hospitalized twice and started getting into trouble with the law.

Now, José worries his son’s mental illness could lead to deportation.

Undocumented and uninsured

People who are undocumented face many barriers to getting help for a mental illness, says Carrie Chapman of the Legal Council for Health Justice in Chicago.

Undocumented children in Illinois, five other states and the District of Columbia can receive health insurance through Medicaid, according to the National State Conference of Legislatures. But they lose coverage at age 19.

Chapman says that’s about when many people, like José’s son, experience their first episode of psychosis.

“It’s just excruciating for families and for advocates,” Chapman said. “It’s an incredible crisis, that such a vulnerable young person with serious mental illness falls through the cracks.”

Andrea Kovach, a healthcare attorney at the Shriver National Center on Poverty Law in Chicago, said undocumented immigrants also are ineligible for insurance through the Affordable Care Act.

As a result, roughly 4 million adults living in the U.S. without legal status are uninsured, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation. People who are protected from deportation through Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, or DACA, also remain ineligible for coverage.

For them, access to healthcare is largely limited to emergency services and treatments covered by charity care or provided by community health centers.

It’s an incredible crisis, that such a vulnerable young person with serious mental illness falls through the cracks.”Carrie Chapman, Legal Council for Health Justice

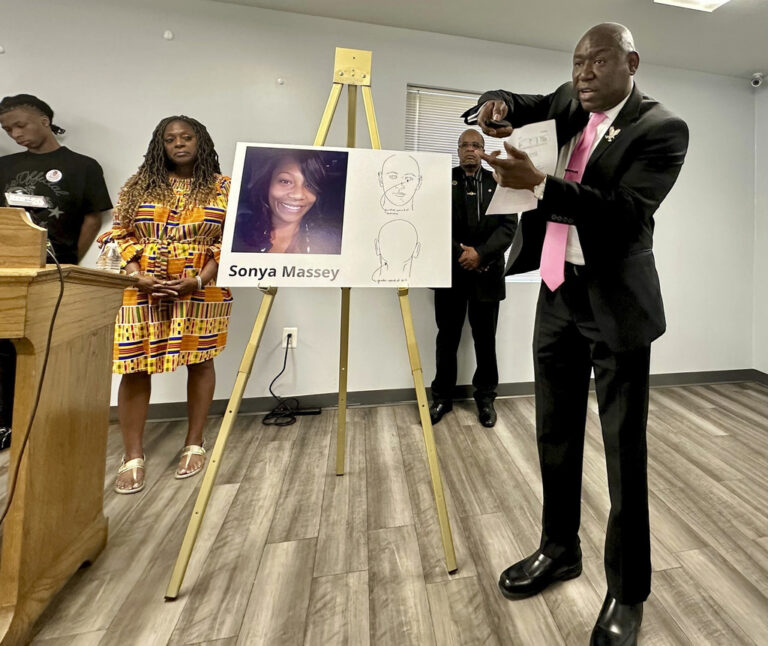

Kovach said the stakes are high for people who are undocumented and unable to access treatment, because that can lead to unlawful behavior—such as violent outbursts during a schizophrenic episode.

“Too many young adults have entered into the criminal justice system for the exact reason that there just aren’t mental health services ready to help them,” Kovach said.

And criminal convictions increase a person’s risk of deportation, she said.

Convicted & fearing deportation

José’s son said that last year, he met with a therapist a few times. He also was taking medication prescribed in the hospital, and that really helped, but without health insurance, he couldn’t afford to pay $180 a month for it.

Back off meds, he struggled and got into trouble with the law.

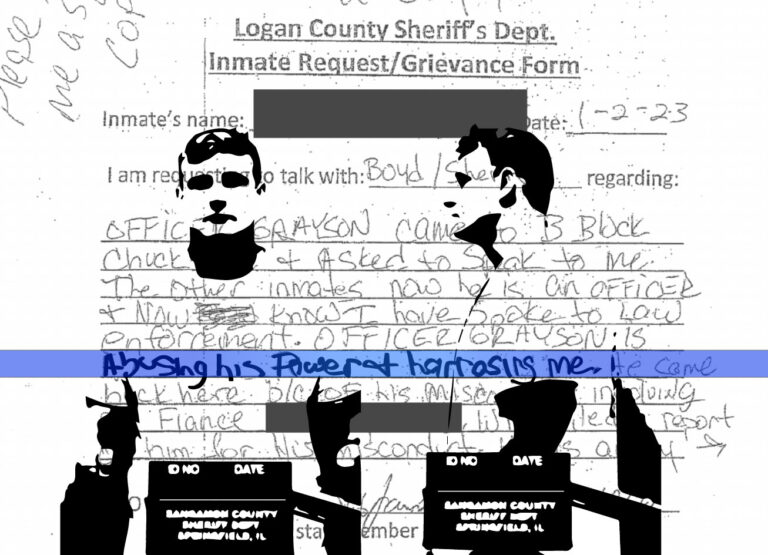

Police were called after several violent outbursts at José’s home in Illinois. During the most recent incident in January, José’s son was arrested after he broke a window and got into a fight with his brother-in-law.

At a hearing at the Champaign County courthouse in May, the judge warned José’s son of the possible consequences:

“If you are not a U.S. citizen, you are hereby advised that a conviction of the offense for which you have been charged may have the consequences of deportation, exclusion of admission to the United States or denial of naturalization,” the judge said.

José’s son pleaded guilty to several charges, including criminal damage to property, domestic battery and traffic violations. He was sentenced to probation for 18 months, which means as long as he stays out of trouble, he can stay out of jail.

Long-term solutions involve policy change, advocates say

Chapman said the only long-term solutions to the challenges people like José’s son face include expanding Medicaid to cover everyone—regardless of legal status—and creating a pathway to citizenship.

“Everything else is kind of a spit and duct tape attempt by families and advocates to get somebody what they need,” Chapman said.

Earlier this month, the U.S. House of Representatives passed the Dream Act, which would give DACA recipients—known as “Dreamers”—a path to citizenship.

And officials in California and New York are taking steps to provide healthcare to some undocumented adults.

New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio announced a $100-million plan called “NYC Care” that would provide coverage to all New Yorkers, including roughly 300,000 undocumented immigrants without health insurance, according to CNN.

And California lawmakers recently approved a budget that would make adults between the ages of 19 and 25 eligible for the state’s Medicaid program if they meet income standards. Officials estimate the program will cover an additional 90,000 people at a cost of $98 million, according to the Associated Press.

As for José’s son, he recently found a pharmacy that offers a more affordable version of the prescription he needs—so he’s back on medication and feeling better.

José knows they’re not the only ones facing these challenges.

“There are thousands of people going through these issues with their children and they’re in the same situation,” José said. “They’re in the dark, not knowing what to do, where to go, or who to ask for help.”

If he gets deported, he’d practically be lost in Mexico… I brought him here very young, and with his illness where is he going to go?José, Illinois father

He said his greatest fear is his son will be forced to leave the U.S.

“If he gets deported, he’d practically be lost in Mexico, because he doesn’t know Mexico,” José said. “I brought him here very young, and with his illness where is he going to go? He’s likely to end up on the street.”

This story was produced by Side Effects Public Media, a news collaborative covering public health.

Christine Herman is a recipient of a Rosalynn Carter fellowship for mental health journalism. Follow her on Twitter: @CTHerman