Weather related closings, delays and e-learning days for Monday, December 15

Meteorologists are predicting blowing snow and continued dangerous wind chills on Monday. Click here to see the latest on the forecast. As a result, the following closings, delays and e-learning days are below:

CHAMPAIGN COUNTY

Champaign Unit 4 Schools: full remote instructional day on Monday

Urbana School District 116: e-learning day on Monday

Rantoul City Schools: e-learning day on Monday

St Joseph CCSD 169: e-learning day on Monday

Mahomet-Seymour Community Schools: school is canceled on Monday

VERMILION COUNTY

Danville Public School District 118: e-learning day on Monday

Dangerous cold continues in east central Illinois, Blowing snow is expected on Monday

Click here for winter road conditions from the Illinois Department of Transportation.

UPDATED Monday at 11:19 a.m.

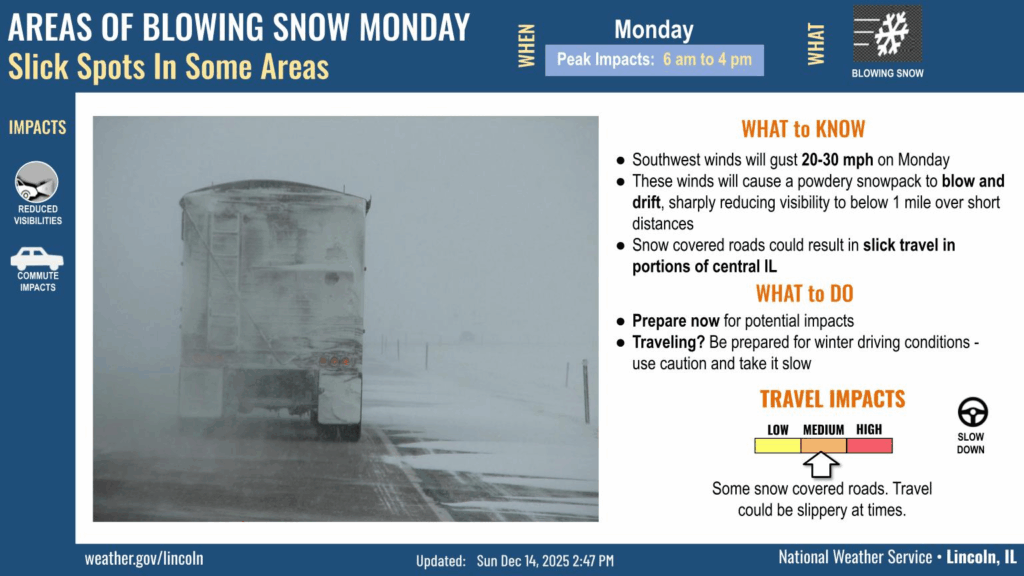

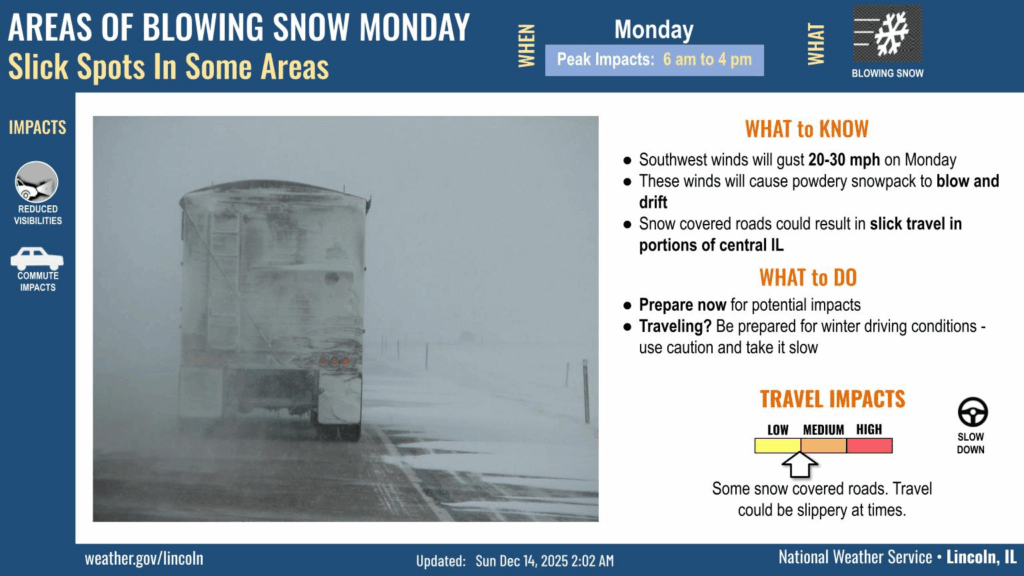

Be prepared for blowing and drifting snow today across central Illinois as blustery southwest winds whip around a fresh, powdery snowpack. Visibility may sharply fall over short distances, and roads may become snow covered and slippery in open areas. #ILwx pic.twitter.com/7cCO71ogNw

— NWS Lincoln IL (@NWSLincolnIL) December 15, 2025

UPDATED Sunday at 8:00 p.m.

From the National Weather Service in Central Illinois and IPM meteorologist Andrew Pritchard:

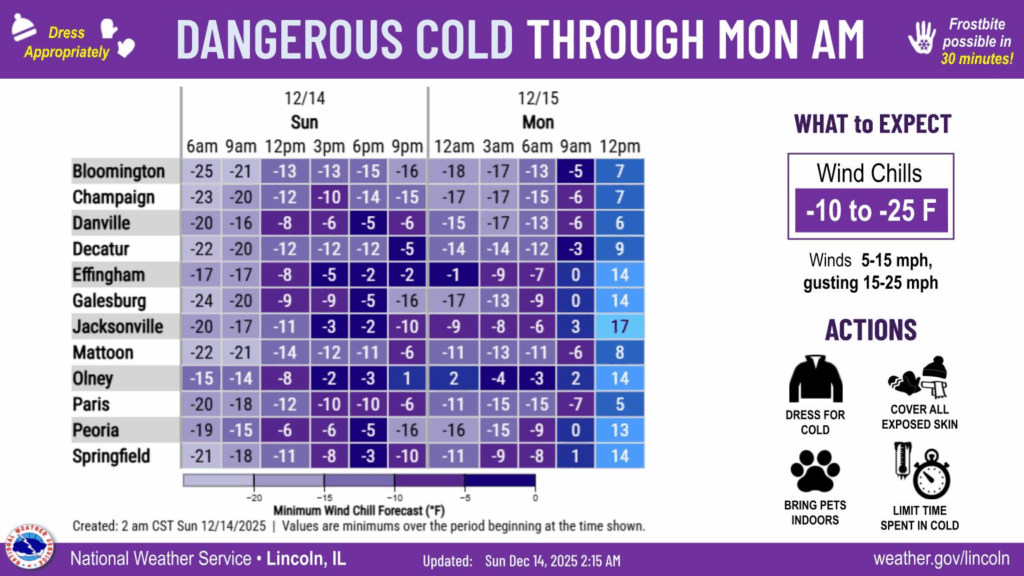

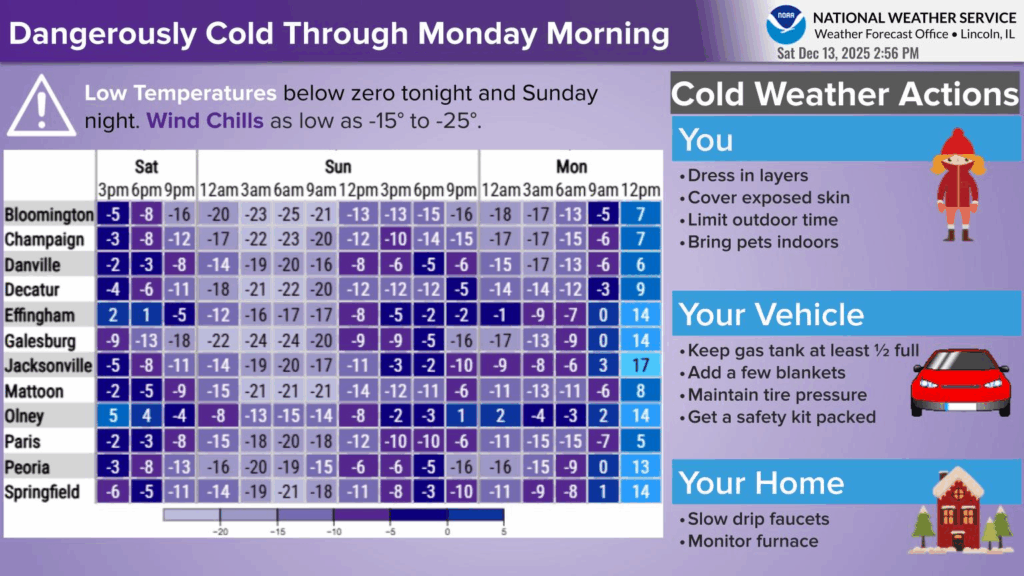

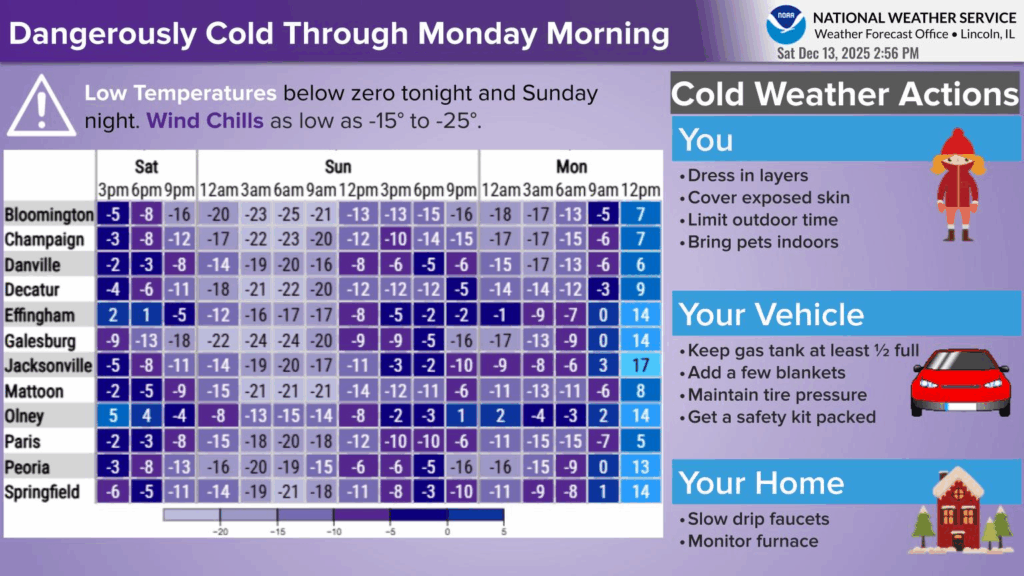

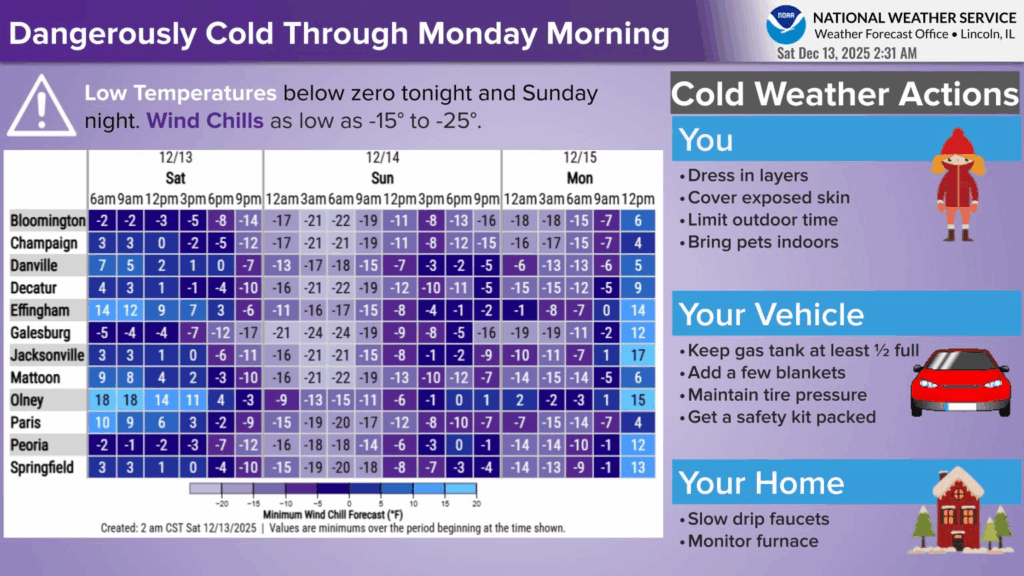

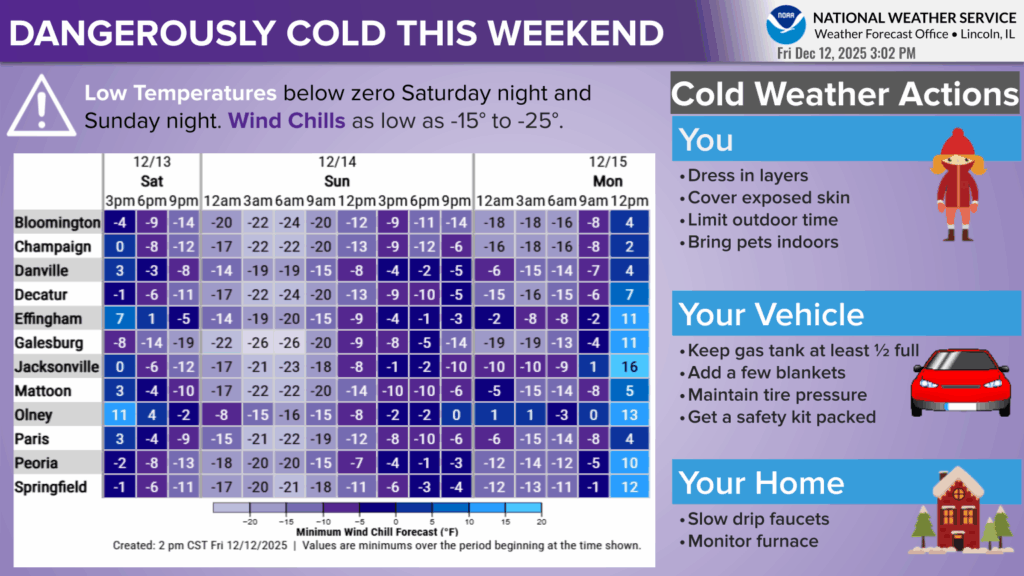

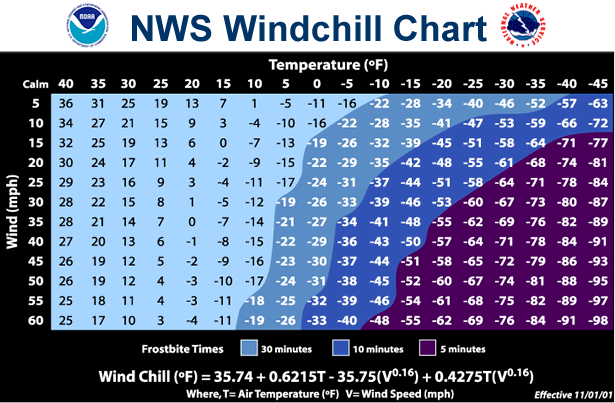

- Dangerous cold persists through tonight across central IL, with wind chills as cold as 12 to 22 degrees below zero at times north of I-70.

- Areas of blowing and drifting snow are possible late tonight into early Monday afternoon. This could ret in localized, sharp visibility reductions, as well as drifting of snow onto roadways. The greatest impacts will be on east-west oriented roads due to soutsouthwest winds gusting 25 to 30 mph on Monday.

- A warming trend is expected this week, with highs in the mid-40s to mid-50s on Thursday.

UPDATED Sunday at 8:30 a.m.

- Dangerous cold persists through Monday morning, with wind chills as cold as -30 this morning, and as cold as -20 early Monday morning.

- Areas of blowing snow are possible on Monday as southwest winds gust 20 to 30 mph. Localized visibility reductions and slick road conditions could develop, especially in open areas.

- A mid-week warm up remains on track, with highs reaching the mid 40s to mid 50s on Thursday. A cold front will drop lows back into the teens by Thursday night.

Updated Saturday at 6:30 p.m.

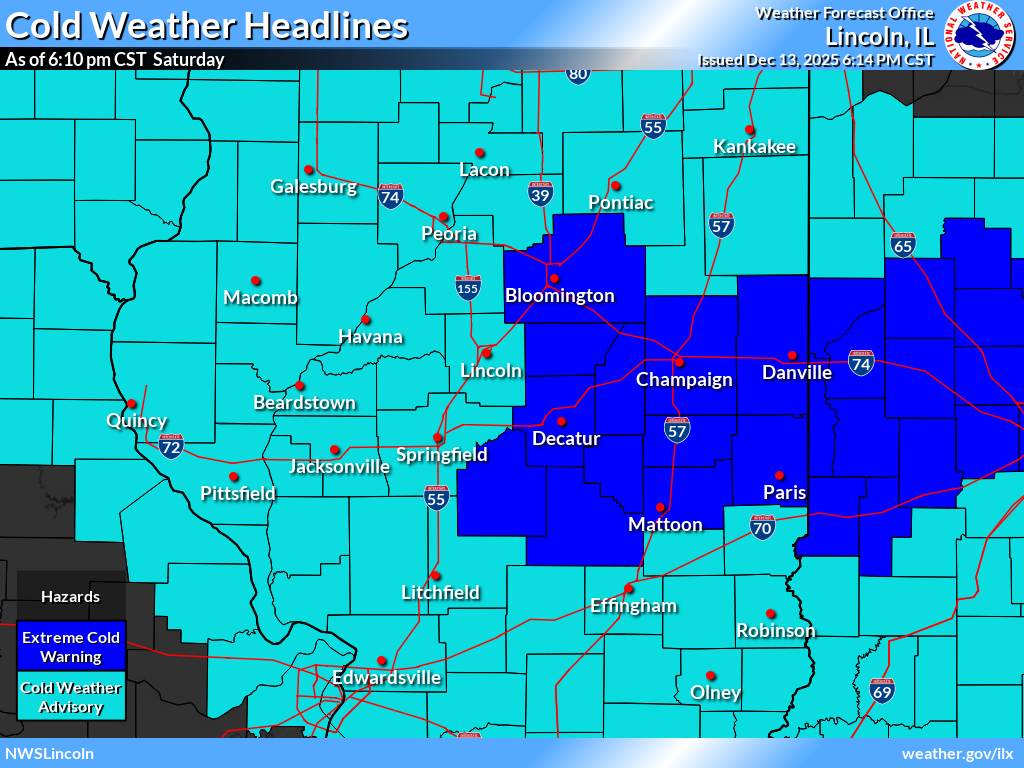

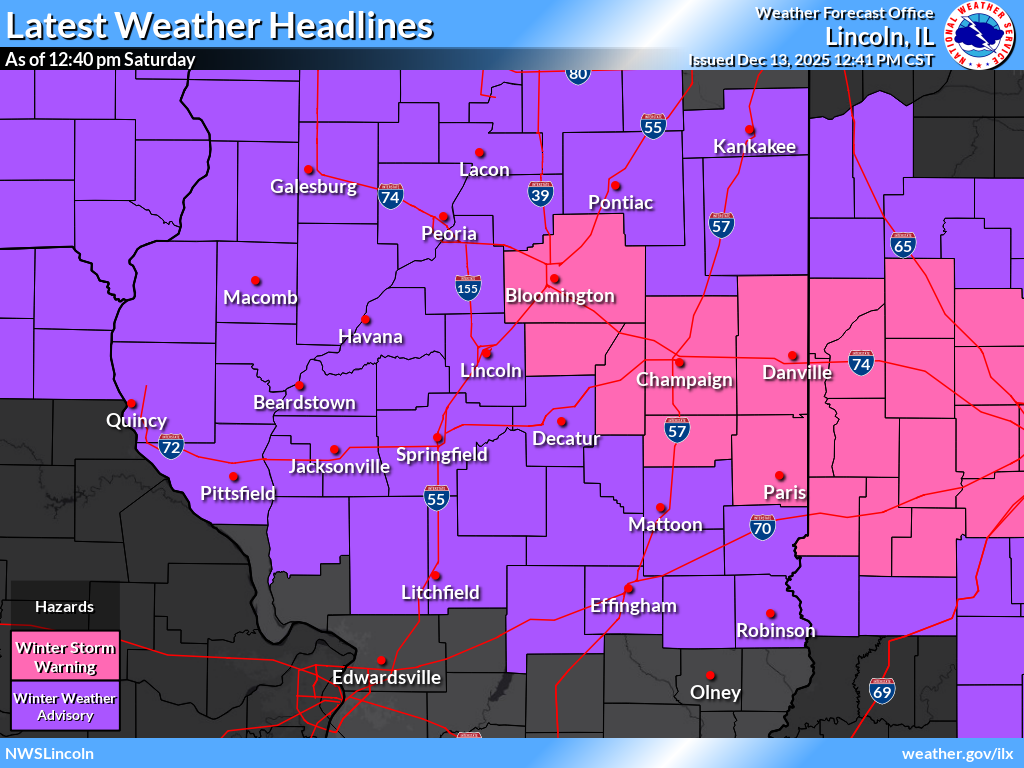

The National Weather Service in Central Illinois has upgraded a warning about imminent subzero weather to an Extreme Cold Warning. Champaign, Christian, Coles, DeWitt, Douglas, Edgar, Macon, McLean, Moultrie, Piatt, Shelby and Vermilion Counties are included in this warning. Meteorologists forecasted wild chills as low as 25 below zero, which could cause frostbite on exposed skin in less than a half hour.

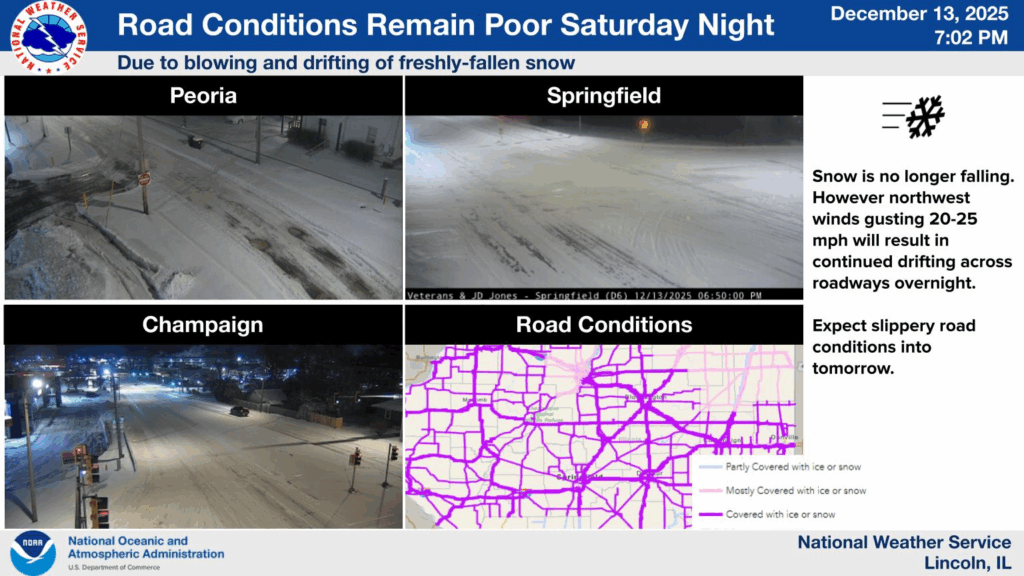

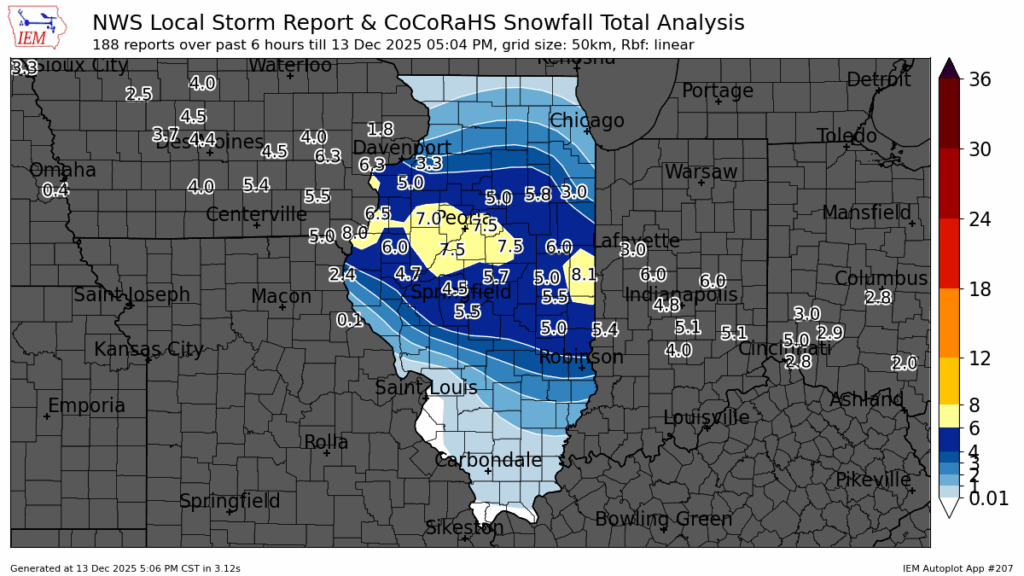

Earlier in the afternoon, between 5 and 8 inches of snow fell across the region.

3pm News update from WILL-AM 580

UPDATED Saturday at 2:30 p.m.

At 2:04 p.m., IPM meteorologist Andrew Pritchard reported treacherous conditions as heavy snow continued to fall in Champaign County and surrounding areas.

Click here for winter road conditions from the Illinois Department of Transportation.

Winter Storm Warning – Saturday now-8pm for Champaign, DeWitt, Douglas, Edgar, McLean, Piatt, and Vermilion Counties. Heavy snow with additional accumulations between 1 and 3 inches are forecasted.

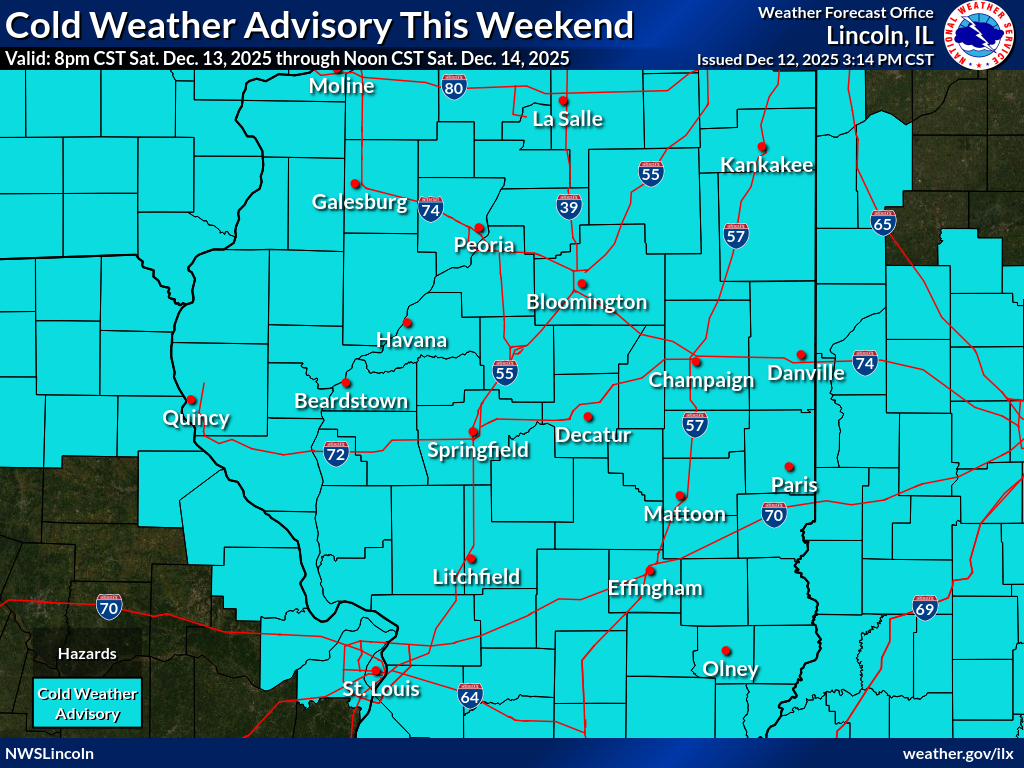

Cold Weather Advisory – Saturday 8pm-Sunday Noon.

As of 2:11 p.m., the National Weather Service in central Illinois is reporting the following snow totals:

- Champaign: 5″

- East Champaign County: 6″

- Bloomington/Normal: 5.5″

- Decatur: 3.4″

- Springfield: 4″

- Danville: 7″

UPDATED Saturday at 12:45 p.m.

Click here for winter road conditions from the Illinois Department of Transportation.

Winter Storm Warning – Saturday now-8pm for Champaign, DeWitt, Douglas, Edgar, McLean, Piatt, and Vermilion Counties. Heavy snow with additional accumulations between 1 and 3 inches are forecasted.

Cold Weather Advisory – Saturday 8pm-Sunday Noon.

UPDATED Friday at 4:30 p.m.

Active Weather Advisories for Champaign County and surrounding areas

Winter Weather Advisory – Saturday 7am-8pm

Cold Weather Advisory – Saturday 8pm-Sunday Noon

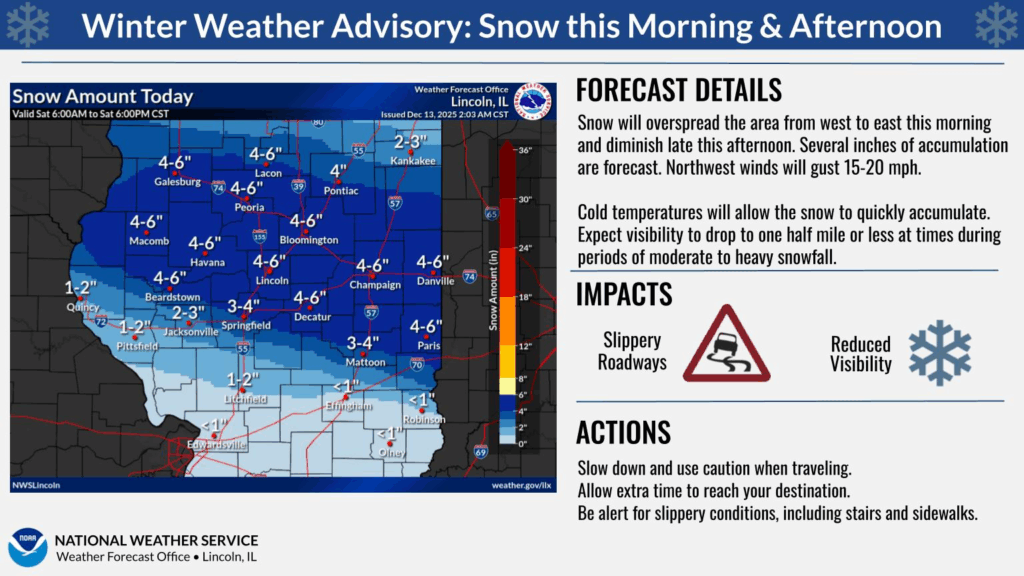

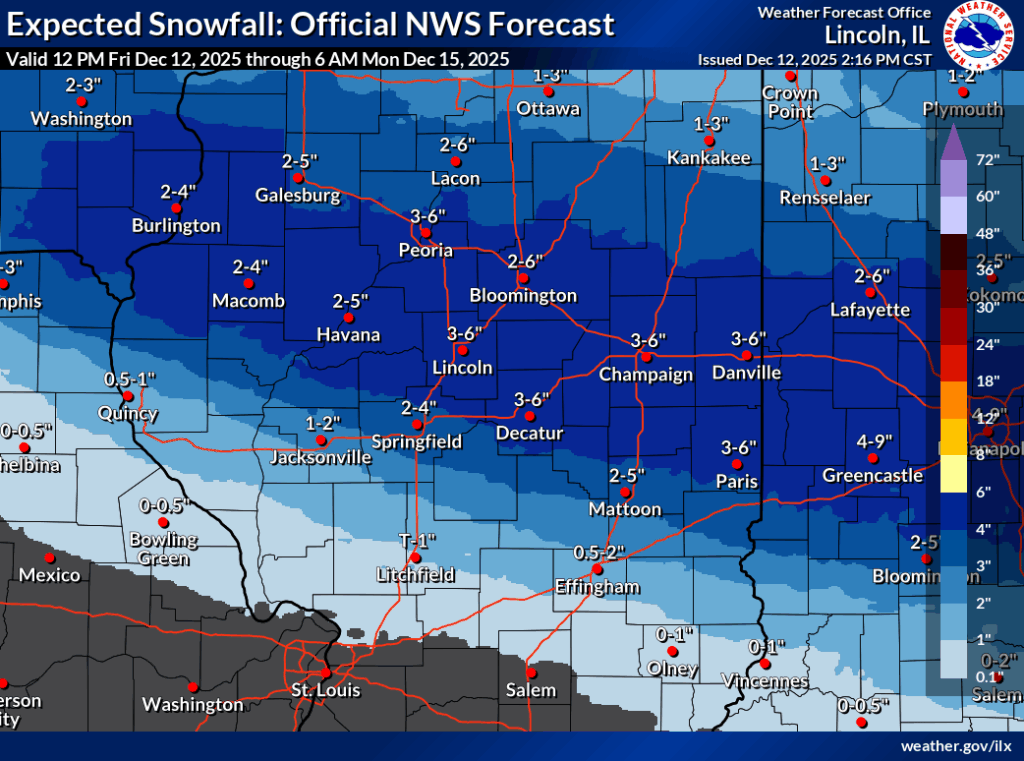

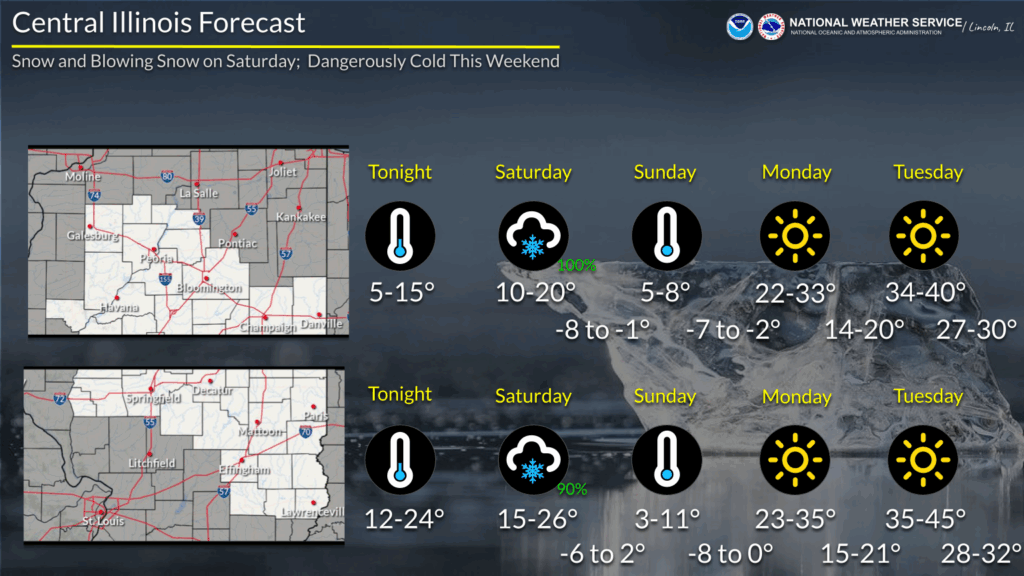

IPM meteorologist Andrew Pritchard said 2 to 4 inches of new snow is expected on Saturday. Skies will clear on Saturday night. The forecast low is 5 degrees below zero. Wind chills between 10 to 20 below zero. Sunday will be sunny and cold with a high of 5 degrees above zero.

UPDATED Friday 1:30 a.m.

Meteorologists at the National Weather Service are warning central Illinoisans to be prepared for bitterly cold conditions the last half of this weekend. Temps will drop below zero across much of central Illinois on Saturday and Sunday nights with resulting wind chill values as cold as -15 to -30.

You’re advised to dress in layers and keep your head and limbs covered because frost bite can occur in less than 30 minutes with such severe wind chills!

The snow system that moved through central Illinois on Thursday night is expected to move out of the area by Friday morning’s drive to work and school. More accumulating snow is expected on Saturday before the subzero temperatures arrive.

Snow is making a comeback in Central Illinois. A Winter Weather Advisory is in effect for early all of central and southeastern Illinois 3 p.m. today through 6 a.m. Friday morning. Total snowfall will range from 2-5 inches, according to the National Weather Service.

Snow will spread into Champaign-Urbana between 3-6 p.m. late this afternoon into the evening with periods of moderate to heavy snowfall continuing overnight. Snow should taper off around sunrise on Friday morning, with around 2-4 inches of new snow accumulation expected across Champaign County, said IPM Meteorologist Andrew Pritchard.

Winds will blow out of the east around 5-10 mph, with minimal impacts from blowing & drifting snow. Still, snow accumulation on roadways could lead to hazardous travel conditions overnight into the Friday morning commute.

Another fast-moving system will bring a healthy dose of snow on Saturday. The latest predictions show a 50-80% chance of greater than three inches of snow for central and eastern Illinois. A surge of bitterly cold air will result in sub-zero apparent temperatures Friday night through Monday morning. Sunday morning has wind chills of -20 to -30 degrees in the forecast.

Weather related closings for Saturday, December 13

URBANA – The following is a list of road and business closings and delays due to heavy snowfall on Saturday. The National Weather Service forecasted 2 to 6 inches of snow north of I-70 in central Illinois. Winter Storm Warning – Saturday now-8pm for Champaign, DeWitt, Douglas, Edgar, McLean, Piatt, and Vermilion Counties. Heavy snow with additional accumulations between 1 and 3 inches are forecasted.

Click here for winter road conditions from the Illinois Department of Transportation.

Click here for the latest National Weather Service forecasts.

Updated Saturday at 2:30 p.m.

- Southbound I-57 in Coles County is closed at Arcola (exit 203) due to what Illinois State Police is calling a significant crash. Several vehicles have crashed due to driving way too fast for the conditions.

- Rantoul Public Library closed on Saturday. It will reopen Sunday at 1:00 p.m.

- Champaign Public Library and Douglass Branch has closed for the day. The main branch will reopen Sunday at noon.

- Danville Public Library has closed for the day.

- Urbana Park District is closed Saturday and Sunday. It will reopen Monday.

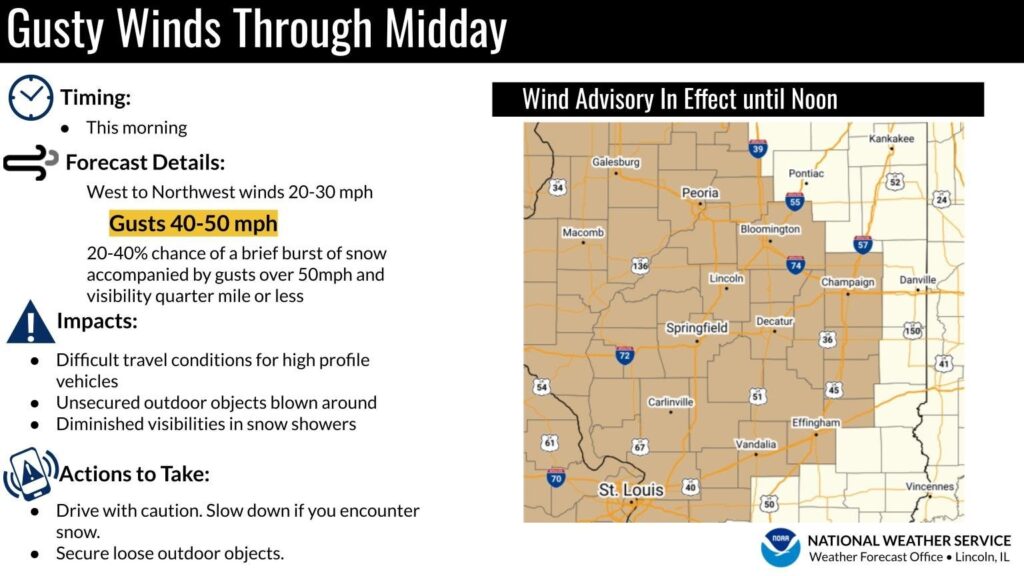

Strong winds expected today in Central Illinois, snow to return later in the week

Central Illinoisans should be wary of gusty winds on Wednesday.

Gusts of 40-50 mph can be expected through midday, according to the National Weather Service. NWS warns drivers to be cautious and secure loose outdoor objects as they could be blown around.

Meteorologist Andrew Pritchard said more cold and snow is expected as well starting Thursday and continuing through the weekend. Saturday and Sunday could see temperatures in the teens and even in the single digits.