This story is part of a partnership focusing on police misconduct in Champaign County between the Champaign-Urbana Civic Police Data Project of Invisible Institute, a Chicago-based nonprofit public accountability journalism organization, and IPM News, which provides news about Illinois & in-depth reporting on Agriculture, Education, the Environment, Health, and Politics, powered by Illinois Public Media. This investigation was supported with funding from the Data-Driven Reporting Project, which is funded by the Google News Initiative in partnership with Northwestern University | Medill.

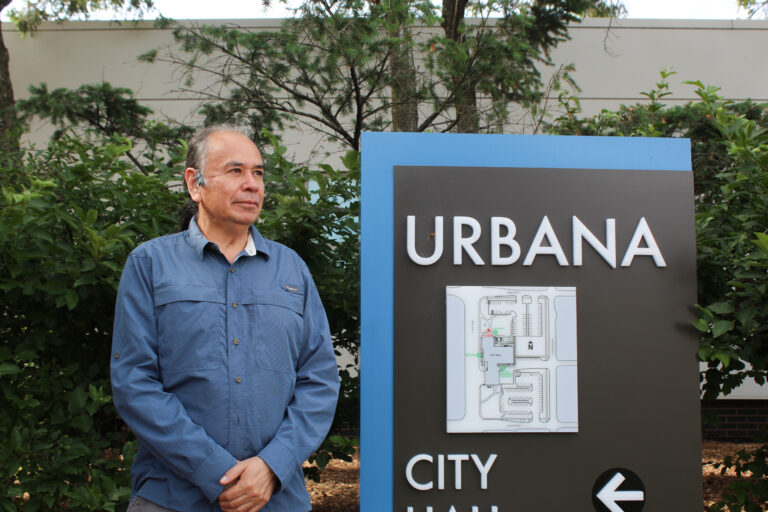

Ricardo Diaz joined the Urbana Civilian Police Review Board in 2011, hoping to bring change to policing in the city of 40,000.

When he moved to Urbana to start a job with the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, he reached out to the city to see how he could help the local immigrant population, as an immigrant to the U.S. himself. That’s when he was recruited to join the Urbana Civilian Police Review Board, which needed members.

Although police oversight wasn’t what he initially bargained for, he thought serving on the CPRB could impact how police treated residents, including immigrants.

But over the years, as Diaz learned more about the board and its limitations, he says, he “woke up.” Now, Diaz says the board’s power is sharply curtailed.

The CPRB operates on an uncommon model. Complaints about Urbana police and staff are first investigated by the department itself. Once the investigation is complete, the Chief of Police decides on next steps — including whether to order additional training or discipline.

If the complainant decides to appeal that decision, only then does the CPRB start a review.

“That’s the step most people don’t take,” Diaz said. “They are not going to question the chief, they’re not going to try to go above him. So there’s very few cases that go all the way up.”

The overwhelming majority of people who file complaints against the police department don’t appeal the decisions — severely limiting civilian oversight over the police for the almost two decades the board was tasked with overseeing the Urbana Police Department.

At his last meeting on May 29, Diaz said Urbana residents want the CPRB to be able to do more actual oversight of police.

“One of our limitations as a board has been that we’re basically an appeals board,” he said. “People see us and ask us questions as if we were actually an oversight board to the police and sometimes people act as if we’re not doing our duty. But the ordinance has been very clear as to the many limitations that we have.”

An uncommonly weak oversight system

The Civilian Police Review Board was created in 2007 after years of glaring police issues in Urbana and calls for civilian oversight of the department.

But during the process of formally creating the board, two major limitations were introduced.

The first limitation: the CPRB can only get involved once a complainant files an appeal. The second limitation: of the cases that get appealed, CPRB cannot hear any that relate to pending criminal or civil court cases.

Additional limitations, introduced during police union contract negotiations, prevent the board from conducting its own investigations and bar community members with felonies from serving on the board.

Even when complainants decide to appeal cases, many appeals sit uninspected for years because they related, at one point, to pending litigation. Other complaints are never even accepted because the person who complained was not a first-hand witness of the incident.

Research by Sharon Fairley, a University of Chicago law professor and former head of Chicago’s civilian oversight agency, shows that the appeals-only model of oversight is “among the weakest,” Invisible Institute and IPM News reported last year.

Compared to most other police oversight bodies across the U.S., Urbana has an uncommon model, according to Cameron McEllhiney, executive director of the National Association for Civilian Oversight of Law Enforcement.

Police oversight best practices generally call for review boards to enter into the process before the chief has made a final decision in a case, McEllhiney said. The CPRB also can’t mandate any discipline or retraining, so their decisions don’t have the potential to publicly set new goals and allow the public to hold the city accountable for effecting change.

Because it’s so rare for complainants to file appeals, the board’s scope removes almost all civilian oversight over misconduct complaints. Police oversight boards throughout the nation rarely have any appeals, McEllhiney said. Part of that, she said, is a symptom of a lack of trust in the system.

“If you don’t have faith in the system to begin with, why would you go and continue the process?” McEllhiney said.

This national trend holds true in Urbana, where only three appeals were filed between 2005 and 2019. After a spike in 2020 — the result of a single person filing the vast majority of complaints — there have been no new appeals between 2021 and 2024, according to data from the Urbana Police Department.

The CPRB could provide more police oversight — but only with significant reforms

Local activists have pointed out flaws in the ordinance that governs the CPRB for years. And in recent years, even the normal functions of the board as mandated have been breaking down.

Meetings are often canceled when board members fail to show up at the last minute, and so-called annual reports often span several years.

Current CPRB member Peggy Patten, a former school board member, said that she was initially surprised by the narrow scope of the board and its limited power.

“Sadly, in my little less than two years, [the board’s powers] have not been exercised much at all, because of the limitations of our board, in terms of attendance and membership, and that's been going on for some time,” Patten said.

Some, like former chair Scott Dossett, say it’s better to have something than nothing. But others, like former city council member Danielle Chynoweth, disagree. She championed the creation of the CPRB and voted in favor of the ordinance that created the board.

“It was a placeholder, so that we said we had something, which sometimes can be more dangerous than having nothing at all,” said Chynoweth, who now serves as supervisor of Cunningham Township.

In June 2020, community members created a petition outlining a list of failures by the CPRB and calling for broad structural reforms. When residents used the petition to call out the board’s ineffectiveness, Chynoweth said she regretted even being associated with its creation.

“It was in shambles,” she said. “I was ashamed that I had ever tried to organize a civilian review board.”

Diaz, who stepped down on May 29 after 13 years on the board, attempted to address many of these issues during his four-year tenure as its chair. Now, Diaz is recommending that both board members and city officials consider a series of suggestions made in the 2020 petition that would, if implemented, result in a complete overhaul of the city’s long-troubled police oversight structure.

“When I realized that getting changes through council would take years, I stepped down after doing what I could,” Diaz wrote to Invisible Institute and IPM News after relinquishing his spot as chair.

Diaz’s departure leaves the board with three vacancies and four members — and an ordinance requiring three members to hold a meeting.

A new CPRB chair has yet to be appointed to replace Diaz, City Administrator Carol Mitten wrote in an email. In a recent meeting, board members “mistakenly” took a vote to appoint Tony Allegretti, a current CPRB member, as chair, she wrote, “but it was not binding” because Mayor Diane Marlin has the role of appointing the CPRB chair.

Allegretti confirmed over email that Marlin has yet to contact him about the next step for the board’s new chair.

Pushes for reforms have persisted for years after a violent arrest and onslaught of appeals

On April 10, 2020, a little over a month before George Floyd’s murder by Minneapolis police, Urbana police violently arrested Aleyah Lewis, an unarmed Black woman, in an incident caught on camera by bystanders and captured the attention of Urbana residents after the video went viral online.

Over the coming weeks, community members pressed city officials on what they viewed as an excessive use of force while residents called on the CPRB to address the arrest.

But because no one had formally complained and appealed, CPRB members argued the ordinance didn’t allow them to do anything. So, Urbana resident Jane McClintock decided she could complain about Lewis’ arrest herself to ensure the board had the opportunity to look at the police’s actions, which videos show officers tackling Lewis to the ground, punching her in the head and kneeing her in the ribs.

“I thought, well, I could complain because it also seemed like the board was interested in having a conversation about it,” said McClintock, a UIUC architecture graduate and engineering technician who serves on the Champaign County ACLU steering committee. “They themselves had concerns.”

So, McClintock got the paperwork, filled out the complaint and even had it notarized. However, her complaint was rejected because the ordinance requires complaints to be submitted by someone who witnessed a “first-hand account” of the incident. McClintock had only watched the viral videos.

A memo written later that year by an attorney hired by the city to support the CPRB’s rejection of complaints about Lewis’s beating claimed that “merely watching a videotape does not constitute ‘first-hand knowledge,’” and that accepting such complaints would violate the FOP agreement.

To bolster his case, the attorney cited arguments from a group called the Force Science Institute, whose founder has been accused of “pseudoscience” that serves to encourage excessive force by officers. The memo was first published on the website CheckCU and was verified by Invisible Institute and IPM News.

The barrier limiting only direct eye or ear witnesses from complaining, McClintock said, severely limits the kinds of incidents that might benefit from civilian oversight in Urbana. She would go on to co-author the CPRB reform petition later that year.

“This is a very unreasonable and unproductive rule that is keeping the CPRB from being able to function in a meaningful way,” she said. “For a lot of the incidents that might need oversight, the folks who are directly involved are often also feeling vulnerable. So asking them to take on the burden of doing the complaint is really an unnecessary hurdle.”

Then, a few weeks later, “George Floyd changed everything,” Mikhail Lyubansky, a CPRB member who was appointed chair in May 2020, told Invisible Institute and IPM News last year.

At the time, there was “a lot” redacted from information given to the CPRB, he said, and no way to track any individual officer’s history. Lyubansky pledged to reform the CPRB after hearing community input.

Lyubansky would step down within a few months — one of several members to leave the board during that time. Diaz, also a longtime board member serving as co-chair at the time, replaced him. Lyubansky admits he didn’t think the board was effective at creating material reforms.

“I don't think we were making change,” he said in a recent interview. “But I do think that the police officers were aware of us and I thought that we did create some accountability.”

A resident tried to test the complaint system. It broke down

In 2019 and 2020, Urbana resident Christopher Hansen began filing dozens of complaints and appeals about the Urbana Police Department. The log of cases quickly climbed from the department’s annual average of 10 citizen complaints to nearly 50 submitted in one year.

Hansen became involved in local policing issues in 2018 after being wrongfully investigated for theft by a Champaign officer in 2015. He joined McClintock and others in authoring the 2020 petition calling for major reforms to CPRB.

Hansen set up a security camera outside of his house and submitted dozens of complaints based on what he saw.

The complaints ranged from failure to use personal protective equipment during an arrest in the early days of the pandemic, to repeated failures by officers to stop at a stop sign, to issues about the filing of other complaints.

Some former CPRB members suspect that Hansen was trying to overload the board with work in order to highlight its limitations.

“The appeals only became burdensome when a member of the public chose to challenge the way the board works with the complaints,” said former board chair Scott Dossett. “And that was their right.”

Hansen did not respond to requests for comment, but wrote several posts about participating in the appeal process on two websites, CheckCU and CU-Underground.

The volume of cases impacted meeting attendance and took its toll on the CPRB’s volunteer members, Diaz said in a 2023 interview.

“How do you get volunteers together to review these when each case, at least at the beginning, used to take two to three hours?” he said, noting that the board had also experienced significant turnover.

But Hansen’s complaints “made a difference,” Diaz added. While the CPRB did not side with Hansen in most of the appeals, “the consideration of each one of them has been legit, and the amount of effort has brought out several issues that [Hansen] had pointed to changes that needed to be made,” Diaz said.

“The 2020 cases allowed us to see plenty of gaps,” he said in an interview last month. The board ended up disagreeing with the UPD chief’s finding in at least 23 of the 65 total appeals filed by Hansen, according to an analysis of records released by the city.

Those gaps included the narrow scope of complaints that citizens could file — including the requirements that complainants be first-hand witnesses, complaint documents be notarized, and complaints be filed within 45 business days of the incident. The onslaught of cases also exposed issues with how the department organized and sorted cases, Diaz said.

Before 2020, the CPRB did not have a city staff member who was tasked with collecting information and organizing the logs. Even now, Diaz said, the police department doesn’t have a log for all the documents and materials they compile for a complaint.

“How do you know that you gave me everything?” Diaz said he asked the department. “And how can I hold you accountable?”

Some current and former CPRB members feel the current structure still prevents them from truly holding the city and the Urbana Police Department accountable.

The CPRB ordinance outlines that the board will send a report to the mayor’s office after every case it reviews, and the city website specifies that the mayor’s office will be involved whenever the CPRB disagrees with a decision of the chief — as it did 23 times with Hansen’s cases.

However, “Although the CPRB completed the Appeal Hearings, the Board did not submit any written reports to the Mayor,” the city wrote in response to a records request from Invisible Institute and IPM News.

Ultimately, without further reforms to the system, all of these smaller questions — how many documents the board could receive while reviewing a case, or whatever kind of report it sends to the mayor — may be moot points; since Hansen stopped filing appeals in 2020, no one picked up the mantle. The board hasn’t received a new case in three years.

It’s been four years since the petition asking for reform. What’s next?

Despite repeated calls to change the model of the Civilian Police Review Board over many years, the board is still operating under that original model which was created in 2007.

That is unlikely to change anytime soon. While some of the reforms suggested in the petition have been implemented over time since 2020, City Administrator Carol Mitten wrote in an email, any consideration of whether the change from an appeals-only model will come only after the city can “see if we can make the existing model work better first.” A presentation she made in October 2020 dismissed most of Hansen’s complaints as “less significant” because she categorized them as being within “administrative/procedural” or “car/minor operational” categories.

She also wrote that the city intends to take into account the “considerations” of BerryDunn, a consulting firm the city hired in April 2023 to conduct a review of the services the Urbana police and fire departments provide to the community. In its first report, released in March 2024, the consultants noted some deficiencies with the CPRB, most of which were already known to its members and activists in the community.

The report found, for instance, that the UPD’s policies for tracking complaints do not take the CPRB into account, and recommended more cohesion in the working relationship. However, that was identified as a low-priority reform by the consultants, who did not touch on larger systemic issues with the CPRB.

Those appear to be left to whoever will step up to replace now-former Chair Diaz.

McEllhiney with the National Association for Civilian Oversight of Police says outdated ordinances hold oversight boards across the country hostage — and prevent any meaningful change.

The ordinances that govern police oversight boards can be living documents, McEllhiney said, and models that provide for stronger, more systemic oversight have become more adopted throughout the country. Updated models, like the auditor-monitor model, can help strengthen existing boards, she said.

This model, according to research published by NACOLE, has grown in popularity since 2000. Its broader, more systemic scope allows these bodies to review internal complaint investigation processes, evaluate police policies, practices, and training, actively participate in open investigations, conduct wide-scale analyses of patterns in complaints and communicate their findings to the public — rather than solely review individual complaints.

While many larger departments like Los Angeles, Denver and New Orleans employ this model, McEllhiney said it can also be scaled down depending on the size of the city and the police department. Smaller cities with universities like Davis, California also use this model, she said.

“It's really important for lawmakers to make sure that they thoroughly understand that a civilian oversight entity that does not have any authority is not going to be an effective agency,” she said.

Additional reporting by Jennifer Bamberg and Amelia Schafer, who worked on this story as Medill School of Journalism graduate interns with Invisible Institute.