When prisons offer college courses, they decrease the likelihood that their students will end up back behind bars.

A 2023 analysis of hundreds of studies by the Mackinac Center for Public Policy found higher education in prison can reduce recidivism by up to 15%. It also increases the likelihood of the formerly incarcerated person getting a job after prison and increases their future wages.

Danville Correctional Center has led the state in experimenting with a different kind of education — led by peers.

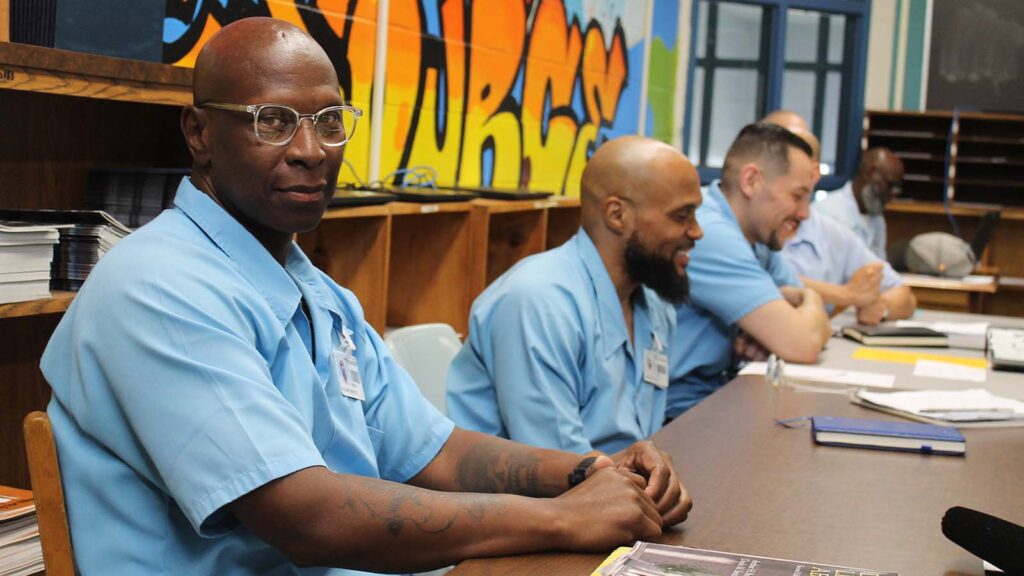

These seven men have served long sentences for charges such as murder, attempted murder and sexual assault. Over time, they have transformed themselves, through learning and teaching, into pillars of the Danville Correctional Center community.

‘A softness starts to settle in’

Larry McCaskill has been in peer education programs at Danville Correctional Center since 2018. He started out skeptical that he would learn anything from Danville’s original peer education program, Building Block. But his thinking evolved as he shared assumptions with Building Block peers he had never said out loud before.

“More than anything, I started to understand how unhappy I was, because my life felt like I had no agency, no power. Like everything was already pre-ordained,” McCaskill said.

He realized there were entire regions of his personality he had never explored — like a love for anime and comics.

“You start meeting the people who love comic books just as much as you’re going to love comic books, the people who play Magic: The Gathering, and you’re like, ‘Wait, I actually like this game.’ There’s a softness that starts to settle in,” McCaskill said.

‘We don’t have concrete evidence the way we would like to’

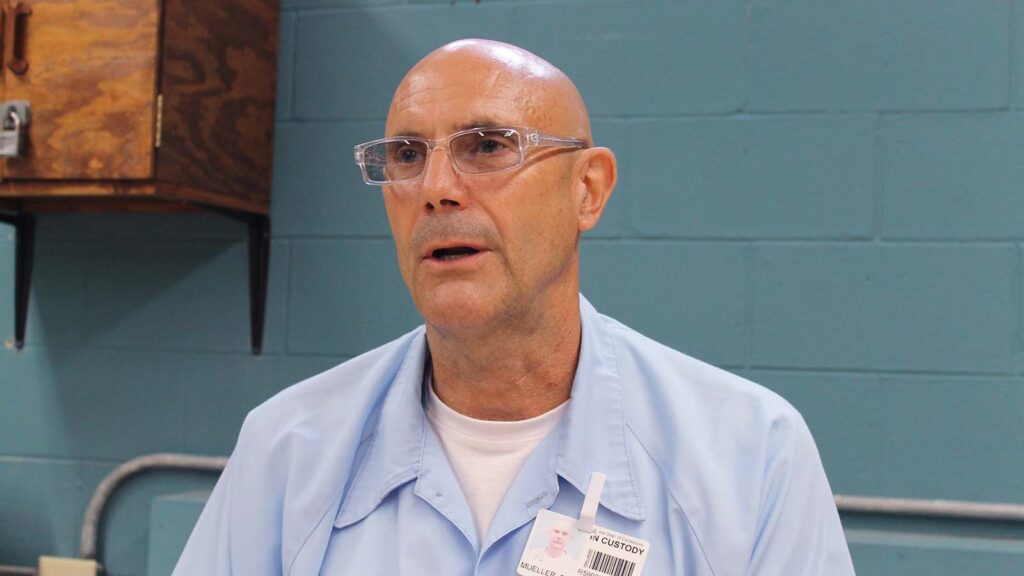

Robert Mueller was a chemistry and physics teacher before going to prison. While in Danville, he helped found a peer education program for those close to getting out.

The program is a unique class in the reentry curriculum: the “Life 2.0” simulation game. In the game, each week counts as a month, with its own set of bills.

“You start out with a $15 an hour wage, and then that allows you then to pay your bills. You have to have a place to live. You have to have a good car, you got to get your driver’s license. If you have a car, you have to put gas in it, you have to get insurance,” Mueller explained.

The participants in the game set goals for themselves and get jobs like car salesman, where they sell cards with cars on them to one another.

“One of our coaches went home and he did contact one of our guys that was still here, one of his friends that was another coach,” Mueller explained. “He said, ‘I didn’t really appreciate at the time how much the simulation was helping me. And when I went home and now I have to pay my bills every month, if I didn’t have that’ — he had been gone for 25, 26 years … he would not have had the discipline.

“He goes ‘I would have forgotten about paying.'”

One issue for Mueller is that the program directors in prison have a hard time surveying former students who have reentered society.

“As an educator, the biggest thing that you have to do is find out whether what you’re doing is working. We don’t know right now. We think we’re doing a good job. Guys seem to like our program and when they leave, they’re appreciative of the work that’s been put in, but we don’t have any concrete evidence the way we would like to,” Mueller said.

‘I had hidden resentment toward my father that I didn’t realize’

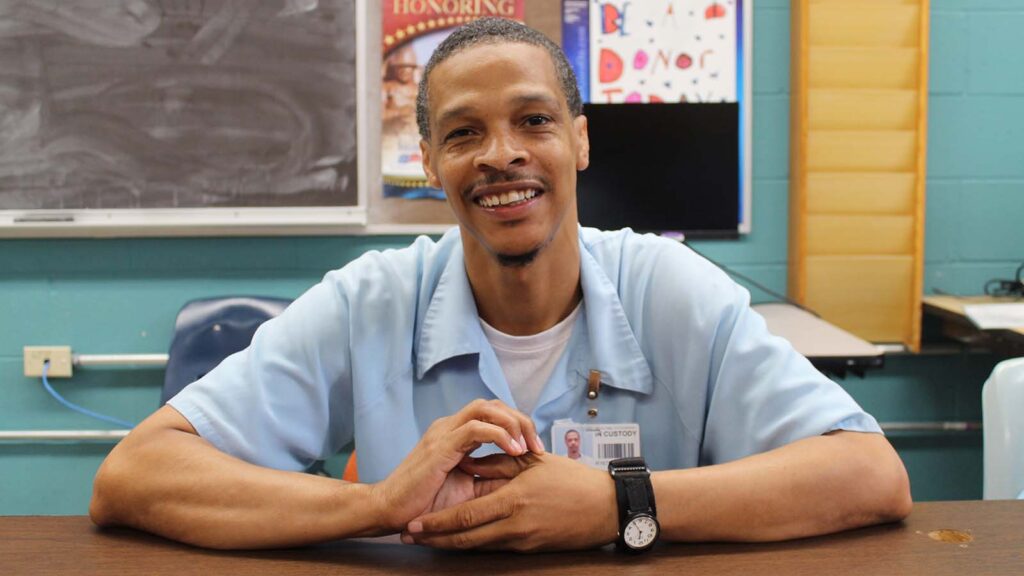

Antonio Jones taught peers before coming to Danville, while in the now-closed maximum security prison, Stateville Correctional Center. He taught peers there about HIV and sexually transmitted infections. He also took college courses there, including a class on ballet.

In Danville, he teaches peers about how to be good fathers. In the process, he has uncovered resentments he feels about his own father’s abusive tendencies and drug addiction.

“He actually passed away since I’ve been gone, so that makes it a much deeper conflict for me, because I’m torn between the pain and the grief of losing him and resenting him for some of the things that I felt he failed me in, like protecting me, providing for me, giving me guidance or any of those things,” Jones said.

Jones has a son himself, who he has not had a relationship with while in prison. He hopes to establish that connection once he gets out. He currently has nine years left on his sentence, for a conviction he got as a teenager in a group of adults.

‘I had to go through it myself’

Maurice Williams gets what those in his critical thinking and anger management classes feel.

“Catching my case, it was a pride thing. I could have let it go, but something kept saying, ‘Don’t let it go. Don’t let it go. He thinks you’re a — Don’t let it go.’ And so I just waited and waited and I let it build up,” Williams said.

Williams’ trick for his students is to have them ask themselves, “Why?” to practice critical thinking. Why did they want to confront an officer on the wing? Why wouldn’t the office let them do what they wanted to do?

After answering those questions, students find the anger becomes less important, and they find other solutions to handle the problems they are experiencing.

‘I am built as a person to be emotional’

Peter Ganaway loves teaching classes about emotional intelligence.

“As a child in my community, you didn’t get to be angry. If you were angry, you got disciplined for being angry,” Ganaway said.

The idea that he was allowed to have emotions beyond being happy or calm was a revelation to him.

“I am built — literally built — as a person to be emotional. That was very eye-opening for me,” Ganaway said.

Conveying everything he wants to convey to his students can be challenging. The group includes 17 other people with their own agendas and bad days. He has to be the level-headed one getting the discussion back on track, even on his own bad days.

But the result can be beautiful, Ganaway said.

Ganaway remembers someone in his group who never felt he deserved better than the difficult environments he was in.

“He realized in the group, ‘I deserve more than what I get. I deserve better than this.’ He realized his humanity. For me, that was wonderful,” Ganaway said.

‘I should have given myself more credit’

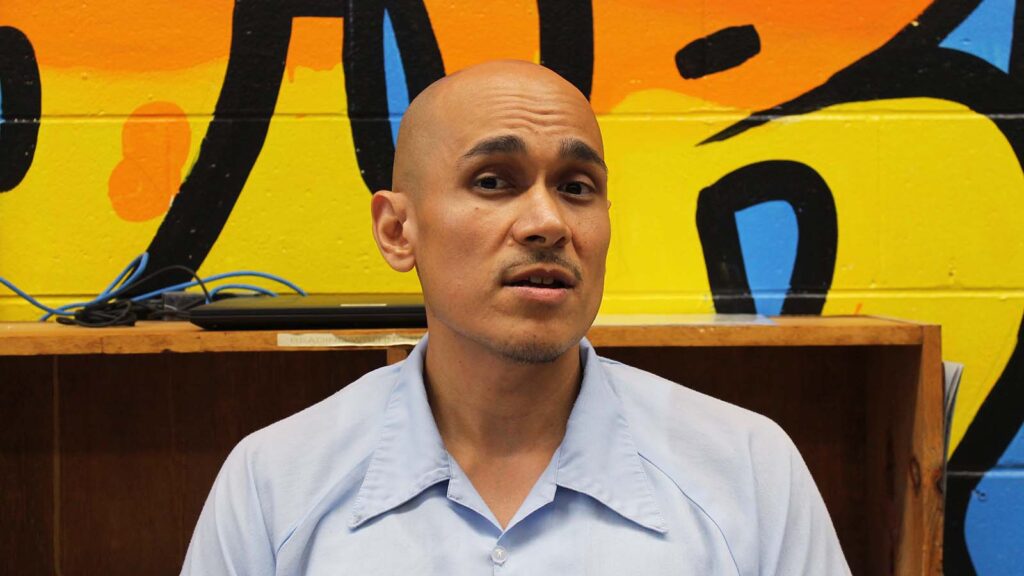

It is Jaime Zarate’s second time in prison.

“I am somebody that re-offended. And the first time coming home, I did not have any of these skills. I never spoke about my feelings or critical thinking or financial literacy,” Zarate said.

Zarate learned who to be from his neighborhood as a child, while his parents worked hard to support the family. When he realized he was going back to prison, he knew he needed to change.

“I would say I had a mask on because I lived in a neighborhood that required me to do that. I had to be tough,” Zarate said. “And I lost myself tremendously in this path that I regret to this day.”

He started to see commonalities that were landing other people from the same social class, level of education and ethnicity in prison — and he decided he could be either part of the problem or part of the solution.

He leans into his new roles, teaching English as a second language classes, being a peer educator and tutoring recently incarcerated high schoolers. He has earned his bachelor’s degree and is studying to get into law school.

When he was young, he tried to not stand out. He didn’t think he was the smartest.

“I learned that I could juggle a lot of things while doing all the peer educators work,” Zarate said. “That’s something I should have given myself more credit for.”

‘You’re a plant that has outgrown his pot’

“I would like for somebody, anybody to recognize the fact that there’s courageous people doing things inside a place that for the most part has been stigmatized,” said James Kral.

Kral said he and other peer educators are doing the impossible. They are helping those no one else will, who others in the prison steer clear of and who staff don’t know how to handle.

But they don’t have access to the reward they would like for their leadership and 24/7 work. Kral said he and many of the peer educators in the room have asked for clemency, but Gov. JB Pritzker only granted six clemency petitions total in 2024.

Only a very small number of those in prison in Illinois can seek to get out early through parole, by presenting their case of transformation to a parole board. Many incarcerated activists are trying to change that, but the bill has not passed the state legislature yet.

Kral grapples with the feeling that he deserves to suffer for what he did to get into prison. He sometimes still feels that way after thirteen years in prison, becoming a peer educator and working on his bachelor’s degree.

He worries that after completing his degree, he will have nothing else to work for.

“What my partner told me is, ‘I feel like you’re a plant that has outgrown his pot,’” Kral recounted. “A lot of us feel that way. We want more for our lives.”