It was a scheduling mishap that led Kourtnaye Sturgeon to help save someone’s life. About four months ago, Sturgeon drove to downtown Indianapolis for a meeting. She was a week early.

“I wasn’t supposed to be there,” she said.

Heading back to the office, she saw people gathered around a car that had veered to the side of the road. Sturgeon pulled over to see if she could help. A man told her there was nothing she could do, Sturgeon said. Two men had overdosed on opioids and appeared to be dead.

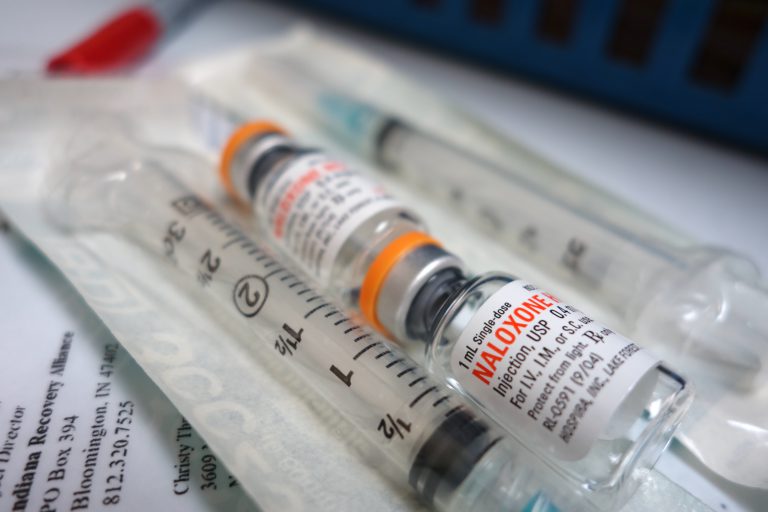

“I kind of recall saying, ‘No man, I’ve got Narcan,’” she said, referring to the brand-name version of the overdose antidote naloxone. “Which sounds so silly, but I’m pretty sure that’s what came out.”

Sturgeon had the drug with her because she works for Overdose Lifeline, a non-profit devoted to distributing naloxone. She sprayed a dose of the drug up the driver’s nose, and waited for it to take effect. About a minute later, she said, the paramedics showed up.

“As they were walking towards us, the driver started slowly moving,” she said. Both people survived.

Earlier this month, U.S. Surgeon General Jerome Adams issued an advisory. More Americans he said, should know how to use naloxone, the opioid overdose antidote, and carry it with them in case they encounter someone who has overdosed on heroin or other opioids.

The advisory includes the tagline, “Be Prepared. Get Naloxone. Save a life.” The idea is that lay responders — people who may encounter an overdose before police or EMS arrive — play a critical role in saving lives.

But actually getting a hold of naloxone can be difficult. Many pharmacies and local health departments don’t stock it, and not everyone can afford it.

Normally, a doctor would have to prescribe naloxone, a prescription drug, for the intended recipient, such as a person who uses heroin. Corey Davis, an attorney for the National Health Law Program, says that the stigma of addiction creates a barrier.

“A person at risk of overdose often times won’t go to their doctor and say, “Hey doc, why don’t you write me a naloxone prescription?’” he said.

Legalizing Access

Every state and Washington, D.C. have passed laws to increase naloxone access for friends and family members of people who use drugs or bystanders. Davis found that most states allow third-party prescriptions which let doctors prescribe naloxone to someone other than the person at risk of an overdose. Many states also allow doctors to issue standing orders to pharmacies to dispense naloxone to anyone meeting certain criteria, such as having a substance use disorder. And organizations such as non-profit groups or local health departments can also dispense naloxone in many states, a process known as lay distribution.

Some states, including Jerome Adams’ home state of Indiana, have issued state-wide standing orders. Indiana allows pharmacies, local health departments or nonprofits that register with the state and follow certain requirements to dispense the drug to anyone walking in their doors.

Indiana increased access to naloxone thanks in part to advocacy from Justin Phillips. Phillips’ 20-year-old son Aaron passed away in 2013 from a heroin overdose.

“I didn’t know there was such a drug as naloxone,” she said. “We were not prepared at all for that potential intervention for someone like Aaron.”

Hoping to prevent other parents from losing a child to an overdose, she started Overdose Lifeline and pushed lawmakers to pass a law, dubbed Aaron’s Law, allowing for third-party prescription and ultimately the statewide standing order. It was first enacted in 2015 and Jerome Adams signed Indiana’s standing order in 2016 while serving at the state’s health commissioner.

But Philips said two years later, many people are still unaware of the law, including pharmacists, which is important: Pharmacies must register with the Indiana State Department of Health to dispense naloxone under the statewide standing order.

Only about half of them do. According to the Indiana Professional Licensing Agency, there are 1,364 active pharmacies in Indiana. Information posted by ISDH shows that 628 of those are registered to dispense naloxone. A spokesperson for ISDH wrote in an email that 115 Wal-Mart pharmacies were missing from that total because they hadn’t yet completed their 2017 reports.

And even in places where pharmacies are allowed to distribute the drug to lay people, they may not always do so. A recent investigation by the New York Times found that half of New York City pharmacies listed with the city as places that dispense naloxone without a prescription, did not have the drug in stock, and some required people to have a prescription to get it.

Cost Barriers

And then there’s the cost. Naloxone prices have increased in recent years and Phillips said in Indiana, two doses of naloxone run between $75 and $150. Side Effects went to two drug stores in Indianapolis, which charged between $80 and $135.

“It’s expensive,” said Brad Ray, a researcher at Indiana University’s School of Public and Environmental Affairs. “People who are users are scraping money together to buy drugs, they’re not prepared to buy naloxone with that money.”

Several U.S. Senators have signed on to a letter urging Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar to negotiate with drug companies to lower the price of naloxone, but according to The Hill, so far it seems Azar has not started that process.

A spokesperson for HHS said that the department had not yet received the letter. “We are working to ensure that there is adequate competition for naloxone, which would lead to lower pricing,” they wrote in an email. HHS did not provide further details.

Outreach

For people who can’t afford the drug, Ray said government and nonprofits can help. Indiana’s health department used federal and state funds to purchase nearly 14,000 naloxone kits since 2016, the state reported. The state distributes those free doses through county health departments. But nearly half of Indiana counties didn’t request kits. Those that did distributed the vast majority of the kits to first responders.

Research from Indiana University’s Fairbanks School of Public Health also found that many doses intended for lay responders were actually handed out to first responders, perhaps because of shortages among emergency services agencies.

The county health departments that participate, Justin Phillips said, need to work hard to get naloxone to people who might use it. People who use drugs, after all, may not feel comfortable going to the government for naloxone.

“You really need to have relationships with the families that are affected, with the individuals who are suffering from opioid use disorder,” said Phillips. “Those are difficult relationships to build.”

Both Phillips and Ray said that syringe exchange programs are an important way to engage people who use drugs and distribute naloxone to people who need it. Scott County, a small rural county in southern Indiana, has operated a syringe exchange program since 2015. As of March 2018, Scott County had distributed 1512 naloxone kits, second only to Marion County, the state’s most populous county.

But although the state legalized such programs in 2015, counties have struggled to launch and maintain them. There are currently eight syringe exchange programs operating in the state.

“Getting it in the hands of users — that’s the trick we need to figure out,” Ray said.

Corey Davis said there is one change that could really help. The Food and Drug Administration should make naloxone an over-the-counter medication to make it easier to access and distribute. FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb has the authority to do so, Davis said, but so far he has chosen not to exercise that authority, nor has a manufacturer brought an over-the-counter version of the medication to market.

“It’s frustrating,” he said.

This story was produced by Side Effects Public Media, a news collaborative covering public health.