David Rothenberg has a keen interest in how humans and nature can connect in ways some may have never thought of before, specifically through music.

A professor of philosophy and music at the New Jersey Institute of Technology, Rothenberg has written books about the musicality behind humpback whales, birds, and even bugs, playing instruments with each species of animal.

In June, Rothenberg is visiting Illinois into make music with the emerging cicada broods. IPM Newsroom’s Kimberly Schofield spoke with Rothenberg about his work, including a concert he performed with cicadas right here in central Illinois.

Kimberly Schofield: David thank you so much for joining me. Have you worked with insects before?

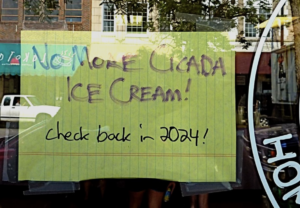

David Rothenberg: I did a book called Bug Music which was timed to come out in 2013 when periodical cicadas came out where I live in New York state, north of New York City. But the first time I heard them was in Illinois and in Missouri in 2011 when I was working on that book and here we are. It’s 2024. The most number of cicadas I ever experienced was in Lake Springfield, Illinois, and we took these cicadas and brought a few of them into Champaign-Urbana for a concert that night. Live cicadas were put on a microphone. They performed. The next day, we brought them back to the exact same place to make sure they weren’t too traumatized.

KS: Do you even have a process of how you approach your interactions with nature when you do these concerts?

DR: Yeah, I’m playing the things that I play. I play wind instruments, clarinets and flutes. In 2011, I started playing electronics live. Since then, what’s evolved? Now we have different kinds of speakers you can put in trees like Bluetooth speakers that can make the sound you’re playing right there, with the bugs not quite next to you. And then I’m also going to do more macro filming and photography with these kinds of really super close-up lenses. And unlike just about any other animals in the natural world, where you’re carefully trying to film them doing things, there’s so many cicadas, you can find whatever you want to film. They’re doing it right around you and you can move them around, pick some up, put them here. They’re very cooperative. They don’t fly away. They’re not scared of you. They have no fear because they outnumber you. So the kind of musicians and performers that work well with this are those, for me, comfortable with improvisation or adjusting their music to playing with these musicians that you can’t really talk to. It’s very humbling.

KS: It is. Like you said, they’ll outnumber and you just kind of have to go with whatever they’re doing. They kind of are like a million conductors to whatever you have.

DR: But they do do things that we know. There’s three species simultaneously to come out, and in some sense six this year, but each brood has these three species that have a characteristic…I would say musical approach to what they do with sound. Like Magicicada septendecim, the most well recognized one makes this main sound called the pharaoh sound. And if you have millions of pharaoh sounds, many of them, they overlap and you just hear the drone. The tale end disappears if you have millions of them doing at the same time. It’s like an acoustic illusion. So the way they organize themselves is around the steady drone.

The other species Magicicada cassini, they make this weird noisy sound and if you have millions of them, you think it could just be noise, but they figured out that’s a problem so they do this wave-like quality. They synchronize themselves and when they’re not singing, they jump up and fly. It’s like doing the wave at a football game or something, but they all do this motion together just to get this sound effect that’s like a waving rhythm so they can hear themselves against that drone.

Third species: Magicicada septendecula and they have like a regular shaker type rhythm all synchronized together. So you have three basic sounds and I could write this down. I could write a composition called Periodic Cicada. Everyone in the group has to do one of these three things.

KS: What would you say to people who are hesitant to even approach the outdoors?

DR: I would just go out listen to it. They’re harmless. They’re not going to hurt you. They’re not gonna just destroy your crops. They might eat some leaves on some trees. Those trees are going to survive. They’re going to be gone pretty soon and you’re not going to see or hear them for 17 years or 13 years or if you’re at the convergent point for 221 years the next time you’ll experience something like this. This is an extraordinary wonder of nature and nature is full of beautiful creatures trying to find a way to survive.