The U.S. trade war with China, now approaching a year, is often framed as hurting manufacturing and agriculture the most. But that’s mainly collateral damage in an international struggle over power and technology that has its roots in the Cold War, when China was still considered a largely undeveloped country.

Intellectual property thefts that were once considered petty are a mounting cost for the U.S. economy — at least $225 billion and at most $600 billion annually, according to a National Bureau of Asian Research report — and China is one the biggest offenders.

The beginnings

President Ronald Reagan talked about the benefits of international free trade throughout his presidency, especially as the Cold War lingered. Many congressional politician hoped opening up trade to markets like China could spread democracy, end Cold War trading blocs and bolster U.S. interests.

“We have begun to write a new chapter for peace and progress in out histories with America and China going forward hand in hand,” Reagan said to a crowd in Beijing in 1984.

It hasn’t worked out like Reagan expected.

“There’s a recognition that although there have been benefits, there have also been costs to the United States from this increased economic relationship with China,” said Aaron Friedberg, a Princeton University professor who’s been watching U.S.-China relations for about 20 years.

China has been strengthening its industries using a top-down model: That is, the communist Chinese government can use its power to carry out specific tasks, he said. For example, it used to require some foreign companies to hand over proprietary information to start working in China.

The opportunity to grow in China was huge, so a lot of companies still made that trade in the 1990s and early 2000s. At that time, Friedberg said Chinese industries were still lagging behind other industrialized nations “so if they were cutting corners and doing things to promote their development of less-advanced industries, I think the feeling (of the U.S. government) was that this didn’t matter so much.”

But China’s growth and laser-like focus on high-tech industries — ranging from cellphones to artificial intelligence — changed things.

According to Friedberg, foreign companies are now less sure they’ll be able to survive in China because “the Chinese are using a variety of methods that we consider to be unfair to promote their own companies to the detriment of our own.

“So, it’s a lot of things that have come together in the last few years that have kind of tipped the balance towards a more pessimistic view of the relationship and pressures to do something to change it.”

A rise in technology, dominance and complaints

While the United States leads the world in high-tech manufacturing, China is a close No. 2, according to the U.S. Trade Representative office, which advises the president on trade. Specifically, China aims to bolster its medical, clean energy, transportation and ag tech sectors, among others — all publicly outlined in its Made in China 2025 initiative.

Countries around the world vie for power in technology sectors, but there’ve been dozens of allegations that China is getting ahead by playing dirty.

To join the World Trade Organization in 2001, China promised that it would no longer force foreign companies to hand over technology or private data to do business there. Still, several companies have told the federal government that this is still a requirement, just one usually spoken aloud in backroom meetings or simply implied.

Cyberattacks tied to China also increased as technology advanced. Coincidentally, many of them were against companies with the kind of technology that China has publicly stated it wants to master.

The Obama administration tried to take China to task, sometimes in lawsuits through the World Trade Organization, and sometimes bilaterally. In 2015, Obama and Chinese president Xi Jinping signed an agreement that neither government would conduct or encourage hacking into private businesses to steal intellectual property. However, a massive federal investigation found that while those attacks may have slowed down, they didn’t stop. Neither did other Chinese tactics, such as direct theft of property like robot arms.

The Trump administration is now going after China more directly. The first major step in the trade war was President Donald Trump putting tariffs on between $50 billion and $60 billion worth of Chinese goods on March 22, 2018; a massive federal investigation about China’s intellectual property theft was published that same day.

Trump could have tried to do this through established World Trade Organization channels, but that could have been a years-long process with uncertain results — and the president was highly critical of the WTO even before taking office.

Ron Kirk was the U.S. Trade Representative for the Obama administration from 2009 to 2013. He said he’s hopeful that Trump’s approach will work, but added group efforts have been shown to be more effective, using allies to pressure China instead of taking the country on alone.

“It is easier for China to comply with a mandate from the World Trade Organization than to say, ‘Oh, the United States came over again and is telling us how to run our economy,’” Kirk said.

Friedberg also said working with allies would help give the U.S. a better chance at forcing China to make significant changes.

“Whatever our complaints about the trade policies of the (European Union) or Japan or South Korea, they pale in comparison to the legitimate complaints we have against China,” he said.

Agriculture’s role

When the Trump administration made the decision to act unilaterally — taking on China without other countries — China retaliated with tariffs on U.S. steel, aluminum and agriculture, targeting Trump’s political base, rural America.

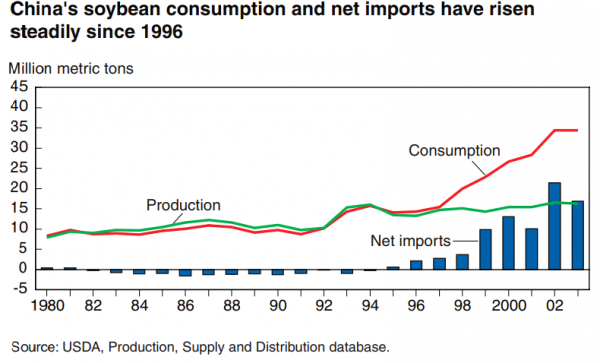

China hasn’t been making major purchases of American agricultural products for very long. Its middle class began to markedly grow in the 1990s, and that drove a greater demand for meat. More meat means more livestock and a need for more animal feed like soybeans.

By the mid-1990s, Chinese imports of soybeans and soybean consumption spiked, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture. And China only emerged as one of the top few buyer of U.S. ag goods in the early 2000’s, according to Dave Salmonsen, senior director for congressional relations at the American Farm Bureau.

But as the current trade war has gone on, the AFB and other farm groups across the U.S. have voiced concerns and encouraged the president to find at least some short-term relief for trade as U.S. and China hash out the major issues over intellectual property theft.

Salmonsen believes, though, a larger agreement is necessary. Some ag companies have been subject to possible Chinese cyberattacks and in one case, a Chinese national was convicted of stealing Monsanto and DuPont Pioneer seeds in Iowa.

There are signs the trade war is loosening ahead of an all-important March 1 deadline. China recently agreed to buy 5 million metric tons of soybeans, which is a win for agriculture groups and farmers. However, that’s a modest amount compared to the 30-35 million metric tons China’s been good for in recent years.

Princeton’s Friedberg is concerned Trump may declare complete victory with these ag wins without changing China’s overall approach to getting U.S. intellectual property. And a larger, Chinese-centric market could create fissures in international trade as certain countries start trading in blocs, leading to goods becoming more expensive for U.S. consumers.

That’s “not the end of the world,” Friedberg said. “That’s a little bit more what the world looked like during the Cold War. We’d prefer not to go back to that, but that may be the direction we’re going.”

Follow Madelyn on Twitter: @MadelynBeck8

9(MDM5MjE5NTg1MDE1Mjk1MTM5NjlkMzI1ZQ000))