A $73 million state-funded project in Lake County aims to stabilize the last undeveloped Lake Michigan shoreline in Illinois and help protect native endangered species.

Illinois Beach State Park in Zion on the state’s northern border contains about 10 percent of Illinois’ Lake Michigan shoreline, with 6.5 miles. But the undeveloped shoreline can erode up to 100 feet per year, according to the state’s Capital Development Board, which is partially overseeing the stabilization project.

To mitigate the erosion, the Illinois Beach State Park Shoreline Stabilization Project seeks to build 22 breakwater structures along 2.2 miles of shoreline. The breakwaters will protect the beach, maintaining it for human and animal use while providing natural habitats for local wildlife.

CDB spokesperson Lauren Grenlund said without intervention the beach “would continue to slowly migrate and erode.” The project, she said, “renourishes the existing sandy beach and shelters it from incoming wave energy.”

Its funding source is the state’s Rebuild Illinois capital program, a $45 billion six-year infrastructure plan originally approved by the General Assembly in 2019. Construction at Illinois Beach began in 2023, and earlier this year the stabilization plan received recognition from New York-based water infrastructure advocacy group The Waterfront Alliance.

Illinois Beach State Park is the first freshwater project and first in the Midwest to receive verification under the organization’s Waterfront Edge Design Guidelines, or WEDG. The Waterfront Alliance launched the WEDG program in 2015 and has since certified 13 other projects, mostly in New York City and the surrounding area, though it opened up to other parts of the country in 2019.

Grenlund said the state decided to submit the Illinois Beach State Park project for WEDG certification – at a cost of $12,500 to cover the application fee – as the project is the “highest standard of waterfront design.”

“By achieving WEDG Verification, the Illinois Beach State Park project stands out amongst other waterfront projects as a leader that goes above and beyond standard environmental and regulatory requirements and provides a broad community benefit,” Grenlund said.

The shoreline stabilization plan received a perfect score in the WEDG program’s category of “innovation.”

“Where this one really stood out is that ecological features that they built into the breakwater,” Joseph Sutkowi, Waterfront Alliance’s chief waterfront design officer, said in an interview. “That’s what kind of took this one beyond just a typical breakwaters project, which is often not that environmentally beneficial.”

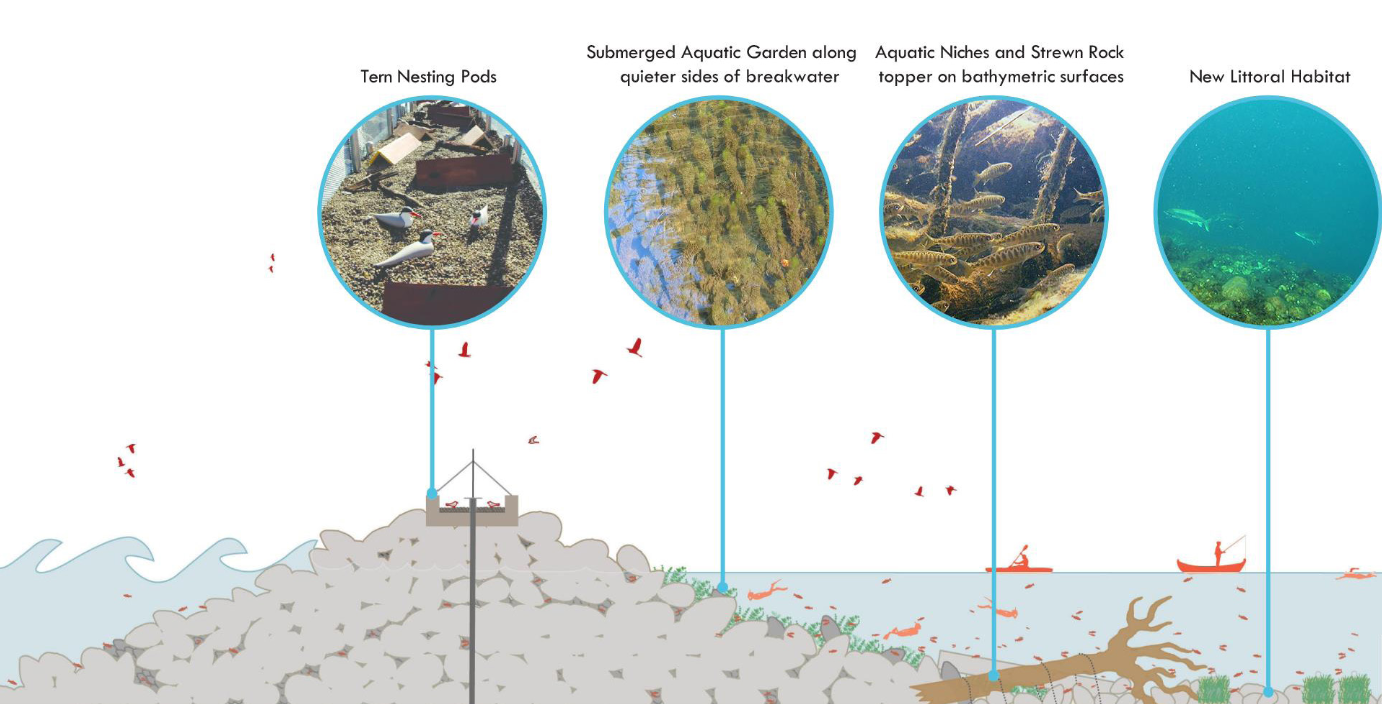

Sutkowi said the ecological features central to the project work to create habitat spaces on the calm, shoreside of the breakwater structures. The top of one of the structures will have 10 built-in nests for migratory shorebirds like the Caspian tern and endangered common tern. Stabilizing the shore and protecting habitats will help protect animals who make their home on the beach, including the endangered piping plover, another migratory bird species.

Under the lake’s surface, reclaimed concrete blocks from the site and native plants will be used to foster aqua gardens and create habitat spaces for species such as mudpuppies and yellow perch.

To protect the new habitats while balancing human use and access of the site, a natural “soft” barrier will be constructed between the breakwater structures and the beach using driftwood and sunken trees. Views from the beach should not be impacted as the structures are mostly submerged and are spaced out, according to IDNR and the Waterfront Alliance.

Maintaining public access has been a factor throughout the process, Sutkowi said. Grenlund said construction around the main swimming beach and conference center only took place in off-season months. Construction at the park’s northern and southern ends is “substantially complete,” leaving the natural beach area in the middle of the park as the only remaining location of further construction this summer, which is expected to be completed in August.

Sutkowi said that beyond recognition, WEDG verification creates a level of accountability as the project is built.

“It’s a tool for the design team,” Sutkowi said. “But it’s also a way for advocates and others to help hold projects accountable for actually creating great sites, because now there’s a standard out there.”

To receive WEDG verification a project must meet 130 out of a possible 200 points. The Illinois Beach State Park Shoreline Stabilization Project scored 146 points. It was designed by the infrastructure firm Moffatt & Nichol. Other companies involved include SmithGroup, Edgewater Resources, Michels Construction Incorporated, and Collins Engineering.