This story was originally published by Illinois Times

The newly appointed Sangamon County sheriff plans to file records requests to obtain information from public agencies that have employed applicants for jobs as county deputies and correctional officers.

Sheriff Paula Crouch also said she will mandate in-person visits to current and past employers, when possible, as part of a more-thorough background check after the 2023 hiring of former Sangamon County sheriff’s deputy Sean Grayson, who shot and killed Sonya Massey, an unarmed Black woman, in her home July 6.

“My thinking is to have a step-by-step background process,” Crouch told Illinois Times after an Oct. 15 meeting of the Sangamon County Board’s Jail Committee. “I know the sheriff before me did have a background process. I’m just kind of making it more in-depth.”

Crouch said not all of the planned improvements have been finalized, including expanding the role of the Sangamon County Sheriff Merit Commission in vetting candidates. She told the committee she will make a presentation in the next month or two outlining the changes and will consider any suggestions.

County Board and Jail Committee member Marc Ayers, a Springfield Democrat who represents District 12, said he was happy to hear Crouch, a Republican, tell the committee she will voluntarily enact several suggested improvements in the vetting process.

Ayers, several other Democrats on the board and board member Annette Fulgenzi, a Republican, were unsuccessful in convincing the full County Board at its Sept. 18 board meeting to put in place some minimum hiring requirements for the sheriff’s department.

County Board Chairperson Andy Van Meter, a Springfield Republican, used the GOP majority on the 29-member board, along with votes from two Democrats, to table an amendment containing the proposed requirements.

Van Meter said the proposal was “well-intentioned” but not legally enforceable because the County Board has no say over how a sheriff runs the department and makes hires. Supporters of the amendment to a resolution that created the Massey Commission disagreed with Van Meter’s interpretation of state law.

Ayers told Illinois Times after the Jail Committee meeting that he had feared Crouch would wait six months or a year — when the Massey Commission was expected to come up with recommendations for state and local officials on how to restore public trust in law enforcement — before any changes would be made in the hiring process.

“It’s good news,” Ayers said in reaction to the new sheriff’s plans and her pledge to be open to voluntarily adopting more suggestions.

“I’m pleased to hear that we’re addressing this stuff soon, and we’re not waiting for the commission to put forth a final recommendation for this, because … lives are in jeopardy,” Ayers said. “This is stuff that we need to know right now before we hire someone.”

Crouch, a retired veteran of the Springfield Police Department, said she is making some changes immediately and not waiting for recommendations from the Massey Commission or future consideration of changes in state law by the Illinois General Assembly.

That’s because she said her 72-member department needs to begin filling seven vacancies among deputies on the streets and nine vacancies among correctional officers who operate the county jail.

It can take months before these professionals go through required training and are available to work, Crouch said.

“I just don’t want us to get so dangerously low,” the sheriff told the committee. “I feel like we need to start with something.”

Crouch, who is paid $165,373 a year, was appointed by the County Board on Sept. 18 to serve as county government’s top law enforcement officer and serve the final two years of Jack Campbell’s four-year term as the elected sheriff. Campbell, a Republican, retired at age 60 after calls for his resignation for role in the hiring of Grayson, 30.

Grayson is charged with first-degree murder in the death of Massey, 36, who had mental challenges and was shot after Grayson apparently was worried she would douse him with boiling water from a pot on her stove.

Massey, a Black single mother of two, was shot by Grayson, who is white, after she called 911 and summoned police to her home shortly before 1 a.m. July 6 when she thought there was a prowler in her neighborhood.

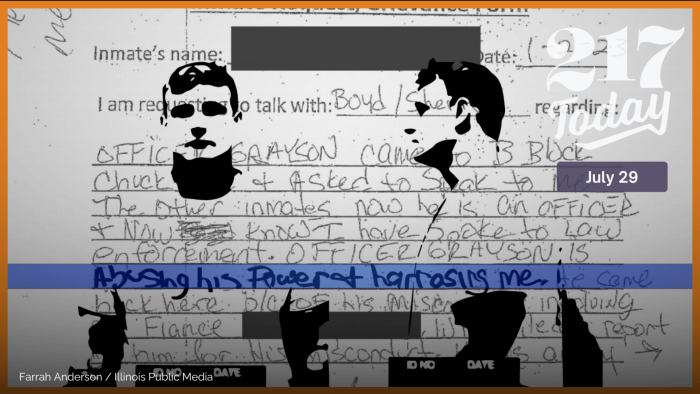

Illinois Freedom of Information Act requests filed by Illinois Times and other news outlets in the weeks after Massey’s death revealed misconduct while Grayson worked as a deputy in 2022 for the Logan County Sheriff’s Office.

There was no mention of that misconduct from Logan County officials in the Sangamon County background check. Campbell later blamed Logan County for failing to provide additional material and implied that Sangamon County asked for background material that ended up not being handed over.

Campbell told Illinois Times before his Aug. 9 retirement announcement that he talked with Logan County Sheriff Mark Landers after Massey’s death. Campbell didn’t say specifically whether Sangamon County asked Landers for a broad range of information from Grayson’s personnel file.

“All I know is that he verified that we didn’t get the information that we had sought,” Campbell said.

Landers has declined comment on Grayson’s time at the Logan County department.

Grayson’s misconduct while employed as an officer with the Kincaid Police Department in Christian County in 2021 — involving the filing of felony drug charges against a man working as a mechanic that later were dropped because of lack of evidence — also didn’t turn up in Sangamon County’s background check.

In fact, documents in Sangamon’s background investigation before Grayson’s hiring included a statement from a coworker of Grayson’s at the Logan County department who said Grayson was a “good deputy but .. needs more extensive training.”

It appeared from the investigation document that no one from Sangamon County talked with Grayson’s supervisors in Logan County.

The background check did include a reference to Scott Butterfield, a retired longtime Sangamon County deputy whose daughter was dating Grayson, in which Butterfield recommended Grayson for employment and described Grayson as a “mellow, non-confrontational person who has good communication skills.”

Details about Grayson’s time with the Kincaid police were reported in a September story by Invisible Institute, a nonprofit public accountability journalism organization based in Chicago; IPM News; and Illinois Times, a weekly newspaper based in Springfield.

Misconduct didn’t result in Grayson being fired from any law-enforcement jobs, and no misconduct complaints about Grayson prior to Massey’s death had been filed with the Illinois Law Enforcement Standards and Training Board despite a 2021 state law that allowed such reports to be considered in decertification proceedings.

Attorneys for Grayson, who has pleaded not guilty and is being held in the Menard County Jail pending trial, have declined comment on his past employment and other aspects of the Massey case.

Crouch said she understands public cynicism surrounding people who are trying to make improvements in hiring and other practices at the sheriff’s department.

“I’m listening to what I’m hearing,” Crouch said. “We have to start moving forward with some changes and try to get it to where it hopefully catches things in people’s backgrounds that we don’t want.

“Some concerns were that people would like the backgrounds to include FOIAs to agencies,” she said. “I have no problem with doing that. That’s an easy thing for us to do.”

It appears that the sheriff’s department under Campbell made a combination of in-person visits and phone calls to current and previous employers of applicants, Crouch said. In-person visits will become the norm in the future, she said, and she is creating a detailed checklist that will make clear which steps were completed, who completed them and when they were completed.

Ayers said he was enthusiastic about Crouch’s attitude, especially when it comes to documenting the filing of FOIAs.

“The more eyes, the better, on this stuff,” Ayers said. “There is a lot of oversight now on who we’re going to be hiring. That reveals loads of information that was never captured in a formal background check or in the personnel file. That makes me a lot more comfortable knowing that.”

The amendment tabled by the County Board included a provision that would have disqualified applicants for deputy, court security or correctional officer positions if they had been convicted more than once of driving under the influence or another Class A misdemeanor within 10 years or convicted of DUI or another Class A misdemeanor once within the past five years.

Grayson had two DUI convictions. He told the Logan sheriff in an email that the first one was in 2015 when he was 21 and on leave from the military following his grandfather’s death. The second one, he wrote, occurred the following year after he was pulled over while driving himself and a friend home from a bar.

State law calls for automatic decertification of police officers if they are convicted of felonies and certain misdemeanors, but not misdemeanor DUI.

Sheriffs have discretion not to hire officers based on their backgrounds, including DUI convictions. When asked whether she would consider DUI convictions disqualifying for applicants, Crouch said, “I think you have to look at each situation.”

Getting the merit commission more involved in the vetting process would help her make final hiring decisions in those situations, she said. “Then it’s not only the sheriff’s decision,” she said.

Crouch said she also is interested in how the Jail Committee and Massey Commission may make recommendations on how to weigh DUI convictions and make other improvements in the hiring process.

“Maybe there’s something we’re not thinking about that’s important,” she said. “I think it’s good to get some insight from people that look at it differently than law enforcement is looking at it.”

Dean Olsen is a senior staff writer for Illinois Times. He can be reached at dolsen@illinoistimes.com, 217-679-7810 or @DeanOlsenIT.