CUBA — Amber Cannon came out as nonbinary in fifth grade in rural, western Illinois.

Around that time, in 2019, a new Illinois law also came out requiring public schools to teach LGBTQ+ history every year.

Cannon followed the news of the law and saw little change in Cuba’s public school curriculum.

“When our laws were enforced; I didn’t see any changes,” Cannon said. “We never talked about any gay people in history unless I brought them up first, or any LGBTQ writers in English.”

Cannon said they did not learn about LGBTQ+ topics in class until high school.

In a two-part series, Illinois Public Media is diving into rural education on race and sexuality. You can find part one of the series here.

Teacher sees lack of LGBTQ+ history in textbooks

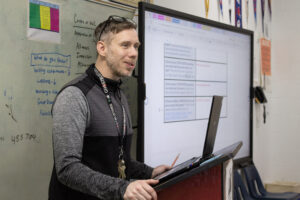

Lewistown High School civics and U.S. history teacher Matthew Peirce incorporates most of the state’s inclusive history mandates. He says textbooks have nothing on LGBTQ+ history, though.

One issue is an absence of LGBTQ+ history in textbooks.

Since 2019, Illinois lawmakers have added the history of Black people before slavery, Asian Americans and Native Americans to the social studies requirements.

In a neighboring town, Lewistown High School civics and U.S. history teacher Matthew Peirce said he included all of this history in his lessons before the law changed.

While he said the laws are great, he was surprised lawmakers thought they were necessary.

“I’m not offended. I’m just kind of surprised. You really don’t think we’re doing this? That’s what I want to ask. Do you really think trained teachers are just skipping over this stuff?” he said.

He said textbooks from companies like McGraw Hill have long included units on everything – except LGBTQ+ history.

“As far as LGBTQ history, there is none,” he said. “So that puts a lot of people in a tough situation. What do I teach for that? That’s very hard.”

Peirce said he covers the Supreme Court’s same-sex marriage decision in his civics class, and he includes the gay rights movement in his civil rights unit.

And he does his own research. He plans to gather material for class during his summer vacation by visiting the Stonewall National Monument in New York City.

Peirce said he would appreciate more state support, like summer history workshops.

New vision for class: no bells, only student questions

Amber Cannon’s social science teacher, Joe Brewer, has found one solution – let students pursue the questions that interest them.

For example, Cannon interviewed an Illinois LGBTQ leader, Libby Lane, the Deputy Director of the Rural Assembly, for Brewer’s history podcast club.

The method is called inquiry-based learning, and it’s been the state gold standard for social studies since 2022.

University of Illinois Curriculum and Instruction Professor Asif Wilson said inquiry-based learning puts students in charge. They ask questions, research their questions, analyze what they have learned and then take action.

Wilson leads the state professional development course on both the inclusive history and inquiry-based standards.

“Maybe we need to explore what is local, what is relevant, what is meaningful to young people during their entire educational process and engagement with us. And that’s hard for teachers,” Wilson said.

He said many teachers are not used to the inquiry-based method or were never trained in it.

Wilson emphasized that educators who encourage students to pursue their interests often encounter roadblocks due to the constraints of a traditional school schedule. Joe Brewer says a student fascinated by Cuba’s mining past faced difficulties arranging meetings with an elderly mining expert during regular class periods.

“The luckiest thing happened; Braxton got hurt in a football game. And he couldn’t go to PE one day. And we were able to get permission to can we go to Mr. Murray’s house during school, so he can ask him these questions,” Wilson said.

Amber Cannon thinks LGBTQ+ education should go beyond individual projects. They especially would like to see more inclusion of LGBTQ-plus perspectives in health class.

“I think if it was talked more about in school, from a younger age, that would be a lot easier for kids to understand. Kids don’t start with biases. They come from parents and the people around them. So if there’s a way to get rid of that bias very early via preschool or kindergarten, that would be a very beneficial thing,” Cannon said.

For their summer break, Cannon is writing a novel, which features a genderfluid main character.

Matt Peirce is attending workshops with Joe Brewer. He also plans to ask his fellow teachers what they do for the LGBTQ+ requirements.

In the fall, the next history requirement kicks in. Public school teachers will have to cover one unit of Native American history, including information on modern, urban populations within the state.

Emily Hays is a reporter for Illinois Public Media.