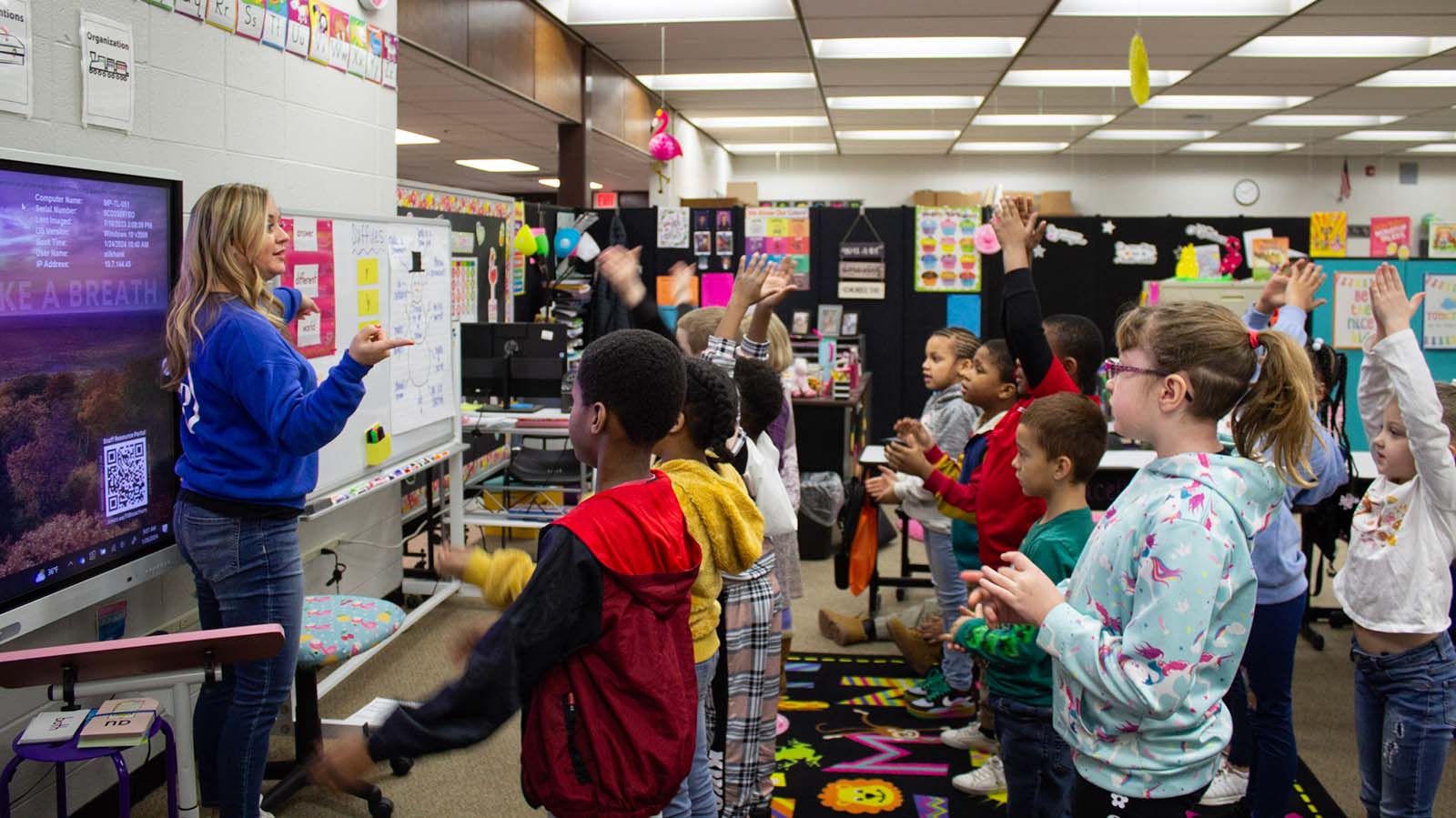

DANVILLE — On a Friday morning at Meade Park Elementary School in Danville, second grader Calvin Cowen is practicing his reading with a teaching assistant.

Calvin hasn’t read the book before, and by chapter two, he tries to convince the assistant teacher that the book is too hard for him. She reassures him that he is reading well.

He does make it to the end of the book – by sounding out the new words.

“Each week, we have a new sound of the week to work on. We practice it and then Fridays we test,” explained his teacher, Kelly Alikhan.

This is called phonics, and it’s one of the teaching strategies emphasized in the new Illinois Comprehensive Literacy Plan.

Why does Illinois need a literacy plan?

Over one in three Illinois students – 38 percent – did not have basic reading skills by fourth grade, according to the 2022 National Assessment of Educational Progress. That’s just above the national average.

Struggling to read in elementary school affects students through high school and beyond. Students who don’t read well by the third grade are more likely to drop out or take longer to graduate, according to the education-focused Annie E. Casey Foundation.

Black and Hispanic children are even less likely to be proficient than white children.

“We have not been serving our Black children well. We need to interrogate why,” said Chicago-based literacy consultant Tinaya York.

York is a member of the Illinois Early Literacy Coalition, which helped push legislative change.

Signed into law in July, Senate Bill 2243 required the Illinois State Board of Education to create a literacy plan. The law emphasizes the plan should help school districts adopt evidence-based teaching strategies, including phonics.

ISBE officially adopted the literacy plan on January 24. Read it here.

Why does phonics matter?

In 2001, Congress commissioned a meta-analysis that found systematically teaching kids to sound out words works better than encouraging students to guess words based on story context.

Encouraging students to guess words is called whole language theory. While whole language theory includes phonics lessons, they are usually as needed and less structured.

But whole language theory has been very influential and many teachers have been trained to de-emphasize phonics.

“You can have classrooms where students are doing a lot of independent reading and time but haven’t really learned how to read the books that they’re doing,” York said.

Journalism about how whole language theory came to be so widespread and why it does not work for all students has pushed a national movement to reintroduce structured phonics lessons into classrooms. Other states have passed similar laws, some with more stringent mandates than others.

Illinois State Board of Education Director of K-12 Standards and Instruction, Erica Thieman, helped write the plan. She said the goal of the plan is to guide districts to more evidence-based practices – not just phonics.

“It is a foundational skill. It’s not the entire focus of the plan. But it’s definitely an important piece of evidence-based literacy instruction,” Thieman said.

Should districts have to update their curricula?

The Illinois Comprehensive Literacy Plan is just a guide for school districts. They don’t have to do anything different under the law.

That’s a concern for York.

“We’re inviting people to try to do the right thing. That’s how [the law] is written. That makes me say it may not have the impact that we would want it to have,” York said.

Thieman said mandating changes would be difficult, because so many administrators and teachers would have to learn so much in a short period of time. And she says mandates are not always as effective.

“If you can get people to critically reflect on their practices, identify that they may need to consider changes and get them to arrive at those conclusions on their own, ownership of that work is on them. They are going to be more engaged and passionate,” Thieman said.

What’s next?

The state has to prepare training courses for administrators and teachers on the literacy plan by January 2025.

According to Meade Park Principal Tanner DeLaurier, phonics has already been a focus in Danville School District 118 since the district adopted a new reading curriculum a few years ago – so very little will change.

“Really just getting every staff member trained with that and being on the same page, so we have a common language across the board. Even though mobility is high across the district and in Meade Park, students will have the same instruction throughout.”

Despite high poverty rates, the school is doing well, according to the Illinois State Report Card. Black students at Meade Park improved faster in reading last year than their peers at almost any other school in east central Illinois.

Emily Hays is a reporter for Illinois Public Media. Follow her on Twitter@amihatt.