DEKALB — Only one of every three 4th-graders in Illinois is a proficient reader, and that puts the state in the middle of the pack.

Reading is not natural. That’s one thing David Paige says a lot of people don’t really understand. He’s a literacy professor and director of the Jerry Johns Literacy Clinic at Northern Illinois University.

Listen to this story here.

“Almost all of us learn to speak naturally. We’re hanging around, we’re exposed to people and speech just naturally emerges,” he said. “Reading does not naturally emerge. Our brains are not naturally wired to read.”

What he’s getting at is that there’s a scientific process to teaching someone how to read. You can’t just plop them in a room full of Dr. Seuss and Charles Dickens books and hope they soak it up.

That might be a silly example, but Paige says that, in many cases, reading curricula have strayed from reading research. And you can see it in test scores. National Association of Education Progress reading scores fell by 3% this year.

“Three points doesn’t sound like much — it is huge. It is a massive, massive drop,” said Paige.

Only one of every three 4th-graders in Illinois is proficient at reading. And Illinois is still in the middle of the pack when you look at the whole country.

It’s bad, but he says it’s not new. Reading scores have been bad for a long time. So, how do we fix it? How should we teach kids to read then?

Paige says it starts with phonics. Phonics lessons teach the relationship between letter combinations and the sounds they make. For example, the word “cat” has a “cuh” sound from the “c” and the “at” sound from the “a” and “t” like in “hat” or “bat.”

It might sound simple, but he says it’s a critical part of the process.

“If you can’t get to where you can pronounce the words fluently, you never really get to much comprehension,” he said. “It’s very difficult because you’re always focusing your attention on ‘Oh, here’s another word, how do I say that word?’”

Unfortunately, Paige says many schools and educators don’t build that phonics foundation strong enough before moving on to other parts of reading like vocabulary knowledge and language structure.

Pam Reilly is an instructional coach at the Plano School District in Kendall County. She and a team of teachers have spent the past few years revamping their reading instruction.

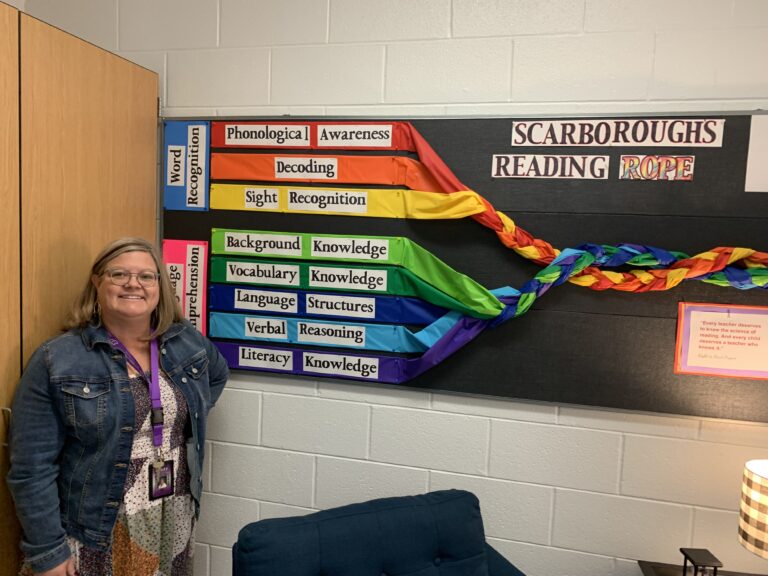

We’re in a classroom at Emily G. Johns elementary school where she’s showing me a colorful illustration of what’s called “Scarborough’s Reading Rope.” There are eight strands that make up the rope, three at the top and five at the bottom. The top side represents word recognition skills like phonics and the bottom, language recognition which gives context to the words and the story they’re reading them in.

“I feel like there is a pendulum swing. 30 years ago, we really focused on phonics, and then we can’t forget about this side of Scarborough’s reading rope, and I think the pendulum swing went more this way, where the focus was not as much on the foundational skills. So, now we’re swinging back,” she said.

The pandemic was a reset button for Reilly. She researched structured literacy and worked with her elementary school teachers for a year on a new program re-learning how to teach phonics. It included 3rd-grade teachers, who weren’t used to teaching it because they had thought kids had it down by then.

They met every week over lunch to pore over data, and Reilly says it’s working.

“We had green across the board for our fall scores for growth,” she said, “so we are headed in the right direction.”

David Paige calls reading instruction a race — from the day a child starts school to until the second or third grade.

“Who decides whether or not a child is a good reader? The child decides that they make that decision,” he said. “And if they’ve decided they’re not a good reader, then it just goes down a very slippery, steep slope.”

They might act out to avoid reading in class, it might make them anxious or ashamed. That’s why Paige says resources and support have to be there for them the minute they step into school.

Pam Reilly says they’re monitoring student progress so they can jump in with support for whichever strand of the reading rope a child might need help with.

But the race is on and Jessica Handy wants to make sure people realize just what’s at stake if we fail students. She’s the policy director at STAND for Children, an educational equity group that advocates for education policy.

“If a student in third grade is unable to read proficiently, they’re four times more likely to drop out of high school,” said Handy, “and if they’re low income that number goes up to six times.”

And she says there are schools of every size and demographic that aren’t teaching reading well. But, in a wealthy district, parents can pay for tutors if their child is struggling to read.

“There are resources there if you can pay for them,” she said. “And it is inexcusable that a kid’s ability to learn how to read is based on whether their parents can afford that or not. It needs to be happening in the schools where the kids are.”

She’s been working on the Right to Read Act — originally introduced in the Illinois legislature this spring but currently being re-written with an aim towards re-introducing it next year.

It could include non-mandatory training modules for teachers and teacher-candidates about evidence-based literacy, tools if districts want to evaluate how well their curriculum works, and short-term grants for schools that want to start a new program but can’t afford it.

Handy says Mississippi is the clearest case study for why statewide literacy policy matters.

“They went from being like 49th or 50th in reading to now they’re middle of the road with us, they’re actually a little bit higher than us,” she said.

But there are other states where comprehensive literacy policies didn’t get those kinds of results. Handy says that’s why they’re trying to take time and include as many stakeholders as they can — like English-language learners — to implement it correctly.

Back in Plano, along with evidence-based methods, they’re trying to promote a genuine love of reading throughout the school.

Every staff member in the building displays their favorite childhood book. Reilly and the 4th grade teachers dressed up as the main character from their book for Halloween. She donned red pajamas and a scarf for her “Miraculous Journey of Edward Tulane” costume. You can even find a customized book vending machine in the hallway where students can earn tokens and cash them in for more books.

It’s kind of fun, maybe even a bit silly, but they’ll tell you that anything that gets kids reading – and wanting to read – is well worth it.