CHICAGO – A measure allowing the construction of new commercial nuclear power plants has bipartisan, bicameral support in the state legislature as the body considers its next steps in meeting carbon-free energy goals while maintaining grid reliability.

Its advocates say the measure would open the door for the use of smaller nuclear reactors to serve as a carbon-free power source when the wind doesn’t blow on turbines and the sun doesn’t shine on solar plants.

While proponents are hopeful, the technology behind nuclear power’s potential resurgence hasn’t yet been deployed for power generation anywhere in the United States. A few examples of small next generation reactors exist across the world, but in the U.S. only one of these smaller nuclear reactor designs has been approved by regulators.

Illinois has the potential to be a hub for research into these types of reactors. A team at the University of Illinois is in the process of building a research reactor that would be the first new licensed reactor of any kind in Illinois in decades, pending federal regulatory approval.

The nuclear industry is all for this push. Representatives of Constellation Energy, the state’s nuclear power company, have said they support any legislation to make it easier to build nuclear reactors. The Nuclear Energy Institute, a nationwide nuclear trade group, estimates that new nuclear could save consumers billions of dollars on energy bills.

But some environmentalists and anti-nuclear advocates say allowing new nuclear technologies represents a fundamental risk to the future of the carbon-free movement and the state’s environment.

Nuclear’s role in ‘decarbonization’

In 2021, Gov. JB Pritzker signed the Climate and Equitable Jobs Act, or CEJA, a landmark bill that, among other things, requires all electric power generation to have zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2045.

Nuclear power has been divisive among those pushing to eliminate greenhouse gas emissions in the energy sector. For some it’s a reliable carbon-free alternative to coal and natural gas. For others it’s a dangerous diversion of money away from renewable resources.

Sen. Sue Rezin, R-Morris, introduced a bill that would lift the state’s moratorium on nuclear reactor construction. Rezin said new nuclear reactor designs could alleviate some problems that will come with more reliance on wind and solar power.

“Three other states around the country have lifted their bans as well because they recognize nuclear – not large nuclear but the advanced nuclear reactors – are a potential answer to the reliability and resiliency problem within their energy portfolio,” Rezin said in a committee hearing.

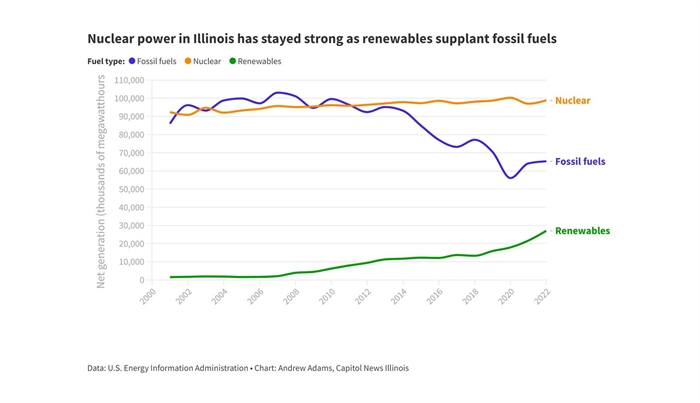

As it stands now, most of Illinois’ electricity production in 2022 came from its nuclear fleet, according to data from the U.S. Energy Information Administration.

The increased prevalence of electric vehicles and the movement toward electric-powered heating and cooling systems – known as electrification – also poses significant challenges to energy providers.

The independent grid operators that serve the state – PJM Interconnection in northern Illinois and Midcontinent Independent System Operator (MISO) for the rest of the state – have identified the need for new power generation due to electrification.

PJM’s most recent load forecast predicts a 21.9 percent increase in their net load over the next 15 years. In a 2021 report, MISO predicted that their system (which covers parts of 15 states) will need drastic amounts of new energy generation over the next 20 years to meet the increased demand from electrification.

Nuclear advocates say that relying solely on renewable energy to meet this demand would be prohibitively expensive. A report commissioned by the Nuclear Energy Institute estimated that aggressive deployment of new nuclear power generation could save customers $449 billion between now and 2050 if the nation meets its carbon-free energy goals.

“Including lots of new nuclear will help make this transition more affordable,” Marcus Nichol, a representative of the Nuclear Energy Institute, told the Senate Energy and Public Utilities committee earlier this month.

Nuclear power’s position as a low-emission method for generating power is well documented. The United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change found that nuclear power generates fewer greenhouse gas emissions over its lifetime than most forms of power generation, including solar power.

Two of the state’s major environmental advocacy groups, the Illinois Environmental Council and the Illinois Chapter of the Sierra Club, oppose lifting the moratorium on nuclear power plant construction.

“We believe that nuclear is not clean energy,” said Jack Darin, the director of the Illinois Chapter of the Sierra Club. “Its full life cycle has very serious impacts.”

After nuclear fuel is used, it continues to emit potentially hazardous radiation for tens of thousands of years. Eventually, this spent fuel should be moved to a long-term disposal facility, although no such facility has ever been designated or built in the U.S. This means waste is often kept on-site at nuclear facilities in pools or in steel cannisters designed to block radiation.

Grundy County has the nation’s only de facto permanent disposal site, and it has been at capacity since 1989. With nowhere to dispose of spent fuel, waste management continues to be an open question for the nuclear industry and the NRC.

Darin also pushed back on some of the concerns about electrification, pointing out that advancements in energy efficiency could reduce the overall load on the electric grid.

“The ideal path for our nuclear fleet is a steady reduction of our reliance on it,” Darin said.

Others who advocate for decarbonizing the energy grid have a positive view of nuclear power. Alan Medsker is a longtime nuclear energy advocate and has worked on campaigns including the Campaign for a Green Nuclear Deal and Generation Atomic.

“We will need to consider existing and new nuclear reactor designs in addition to the other clean energy sources available to us to reach our clean energy goals,” Medsker told lawmakers at a committee hearing on March 9.

A new regulatory landscape?

To facilitate this potential nuclear renaissance, lawmakers are considering two effectively identical proposals to end a moratorium on nuclear plant construction that has been in effect since 1987. The temporary ban was put in place pending the federal government’s designation of a long-term disposal site for nuclear waste.

One bill, House Bill 1079, was introduced by Rep. Mark Walker, D-Arlington Heights, and passed out of committee on Feb. 28 on a 18-3 vote. The second, Senate Bill 76, was introduced by Rezin and passed out of committee on March 9 by a 15-1 vote.

Speaking to his colleagues on the House Energy and Environment Committee, Walker called his proposal “a simple bill with large consequences.”

The bills are part of a nationwide conversation and competition among states to become the next center for nuclear power.

“Some of the states that do not have moratoriums, or those that have recently released their moratoriums such as Wisconsin, are aggressively attracting these new high-tech venture investments,” Rizwan Uddin, the head of the nuclear engineering department at the University of Illinois, told lawmakers. “Despite its long history with nuclear power and its current technical base, Illinois is not even considered an option state due to its moratorium.”

This competition, and the interest in allowing new nuclear construction in Illinois, is being driven by new designs for nuclear reactors that are both physically smaller and that can be deployed at smaller scales.

Small modular reactors, or SMRs, operate at smaller scales than traditional reactors and are prefabricated. While a traditional reactor might produce thousands of megawatts of energy, a small modular reactor would produce a few hundred megawatts of energy or less, depending on its design.

“We’re seeing advancements for nuclear reactor designs that open the doors for industry and business,” Walker told the House committee. “Development of modular and microreactors could power factories, data centers and other industrial facilities that we’ve been working hard to bring here.”

The U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission, or NRC, approved the first of these smaller reactor designs for power generation, a 50 MW concept from NuScale Power, on Jan. 19 of this year. NuScale has active projects where it hopes to eventually implement its new design in Idaho, Wisconsin and Missouri.

Relatively few reactors throughout the world are based on the latest generation of designs, although Russia and China both have active SMRs that were deployed in the past three years.

No commercial SMRs are online in the U.S., meaning their long-term economic benefits (or unforeseen costs) are yet to be seen.

Illinois’ nuclear power stations are all owned by Constellation Energy. The company has no public plans to develop new nuclear reactors in the state, although they support ending the moratorium on nuclear construction.

“Constellation fully supports legislative and policy solutions that eliminate barriers to maintaining and expanding nuclear’s role in delivering reliability, affordability and energy security,” David Snyder, a spokesperson for the company, said in an email to Capitol News Illinois.

Constellation does have an interest in the proliferation of small modular reactors, as it has a partnership with Rolls-Royce to operate a fleet of reactors in the United Kingdom.

Some in the field of nuclear safety aren’t yet convinced about this new generation of designs.

Edwin Lyman is a physicist and director of nuclear power safety with the Union of Concerned Scientists. While he and the UCS took no position on lifting the state moratorium, he likened lifting the policy to “opening Pandora’s box.”

“We have extensively reviewed the safety claims for a range of new nuclear technologies that have been proposed and found that in general they offer few safety benefits compared to current technologies, and in some cases may pose even greater risks from accidents, terrorist attacks or extreme weather events made more probable by climate change,” Lyman said in written testimony to the Senate Energy and Public Utilities Committee.

In a follow-up interview, Lyman said construction moratoriums are one of the few ways states can regulate nuclear safety.

David Kraft is the head of the Nuclear Energy Information Service, an anti-nuclear advocacy group. He said that ending the moratorium could result in the state becoming the dumping ground for spent nuclear fuel.

“This puts a safety and security burden on the state that it didn’t sign up for,” Kraft said.

Kraft said he is particularly worried about ending the moratorium because of lawmakers’ interest in new nuclear models, like microreactors and small modular reactors. He cited the fact that some designs for smaller reactors don’t have safety features required for traditional reactors, like containment buildings.

Illinois as a key state for nuclear research

Beyond the question of regulation, there is the broader matter of Illinois’ position as a place for research and development within the nuclear industry.

Illinois has, historically, been closely tied to nuclear research and nuclear power. The first human-made, self-sustaining fission reaction took place at the University of Chicago in a reactor that its creator, Enrico Fermi, called “a crude pile of black bricks and wooden timbers.”

Despite this, Illinois has no NRC-licensed research reactors active right now.

The University of Illinois is currently working on licensing and building a microreactor much more advanced than Fermi’s, which would be the first of its kind in the U.S. It’s a project that could serve as a case study both for the technology of the next generation of nuclear reactors and the public’s perception of them.

The research reactor is meant to train and educate future nuclear engineers as well as demonstrate the feasibility of using this type of reactor in a power generation grid or industrial setting.

“For advanced nuclear to reach its full potential, we need to demonstrate how these things are deployed,” said Caleb Brooks, an associate professor at U of I’s Nuclear, Plasma and Radiological Engineering Department and head of the microreactor project.

The project is in its pre-application phase with the NRC, meaning that it is filing plans with the regulatory body ahead of its formal application. They hope to be operational by early 2028. The state-level moratorium on nuclear construction does not apply to research reactors, a distinct class of reactors licensed by the NRC.

The project will also demonstrate several technologies that its designers say will ensure safety.

The reactor will be built by Ultra Safe Nuclear Corp. and will use a new design for fuel pellets – fully ceramic microencapsulated fuel, which its manufacturer markets as “meltdown-proof.” Pieces of uranium the size of a grain of sand are wrapped in a hair’s-width thick layer of silicon carbide and densely packed in a pellet that is coated in a much thicker layer of silicon carbide. This should contain the potentially harmful byproducts of the fission reaction.

Potential accidents should also be easier to manage. Smaller reactors, like the one proposed for U of I, will have a level of excess power that can theoretically be dissipated by the material containing the reactor. This is a shift away from the reliance that traditional nuclear reactors have on active, staff-controlled emergency systems like the kind that failed in the 2011 Fukushima disaster.

The microreactor project is also a preview for how the public might react to having smaller reactors closer to population centers. Several residents have publicly voiced opposition, citing safety concerns.

“Those who live, work, and go to school in the Champaign-Urbana-UIUC-Savoy metropolitan area should band together to stop this misguided UIUC nuclear project,” emeritus U of I professor Bruce Hannon wrote in a piece penned for a Champaign-Urbana community magazine.

A complex relationship

Illinois has the most nuclear power reactors of any state, a distinction it was at risk of losing in 2016 and 2021, when Exelon, the then-owner of all the state’s nuclear plants, threatened to close stations for economic reasons. Constellation was created in 2022 when Exelon spun out its nuclear power generation assets into an independent company which now controls the state’s nuclear fleet.

In both 2016 and 2021, the state offered Exelon hundreds of millions of dollars in incentives to keep plants open.

In 2016, after Exelon announced its intention to close its Clinton and Quad Cities power plants, the state legislature passed a law that authorized $235 million in annual ratepayer subsidies over 10 years as part of the “zero-emission standard” program.

In 2020, Exelon announced that it intended to shut down its Dresden and Byron nuclear plants, citing “revenue shortfalls in the hundreds of millions of dollars.” Just over a year later, within weeks of the plants planned closure, Illinois lawmakers struck a deal as part of CEJA to allow $694 million in ratepayer subsidies over five years to keep the plants open.

In a news release after CEJA’s passage, Exelon noted that the law kept Dresden, Byron, Braidwood and LaSalle open through its carbon mitigation credit program. At the time, Exelon CEO Christopher Crane said that the state paying to keep the plants open would help “build a clean-energy economy that works for everyone.”

Now, Constellation appears to be further acknowledging this practice as part of its core business strategy.

In its year-end report to the Securities and Exchange Commission, the company said that “we plan to file applications to extend the licenses of our nuclear fleet to 80 years for the units that receive continued support under federal or state policies or a combination of both.”

That strategy, in conjunction with Constellation’s broader business approach, has literally paid dividends.

“Our strong financial position allows us to return exceptional value to shareholders by doubling our dividend and authorizing a $1 billion share repurchase program,” said Constellation CEO Joseph Dominguez in a news release when the filing was announced.

He further noted that the company has $2 billion in unallocated capital.

Constellation announced in October that it’s applying to extend the life of its Dresden and Clinton plants for 20 more years. If the application is approved, Clinton could operate until 2047 and Dresden could operate until 2051.

Elsewhere in Illinois’ fleet, Constellation announced it will spend $800 million to increase the output of the Braidwood and Byron plants by approximately 135 megawatts, which the company said would be enough to power roughly 100,000 homes each year.

“The units today are in better shape than the day they were commissioned, so we could go a lot longer,” Constellation CEO Joseph Dominguez said at an Aspen Ideas Conference session on March 8.

Nuclear critics have taken issue with the relationship the state has with its nuclear energy provider.

“For decades, the only way you could get renewables built in Illinois was if Exelon got something in exchange. Now it’s gonna be Constellation,” Kraft said. “They’ll come back in a few years for more bailouts. They’ll be complaining even if the small modulars come online because the market is lowering the prices. They’ll come up with excuses.”

Capitol News Illinois is a nonprofit, nonpartisan news service covering state government. It is distributed to more than 400 newspapers statewide, as well as hundreds of radio and TV stations. It is funded primarily by the Illinois Press Foundation and the Robert R. McCormick Foundation.