DANVILLE – Brennon Hightower says Black history is lacking in the education her two sons receive at their public school in Danville, a city in east-central Illinois. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Hightower decided to homeschool her sons — aged 10 and 15 — using curricula she found and liked. But even that material included very little about Black history, she says.

Listen to the story here:

“When I went to the U.S. history [section] for both of them, for my ninth grader, there was a little bit about history, not much. And then I saw the 13 colonies. They had nothing about African Americans in there. And then for my youngest son, their person of interest was Harriet Tubman, but not many more,” she says.

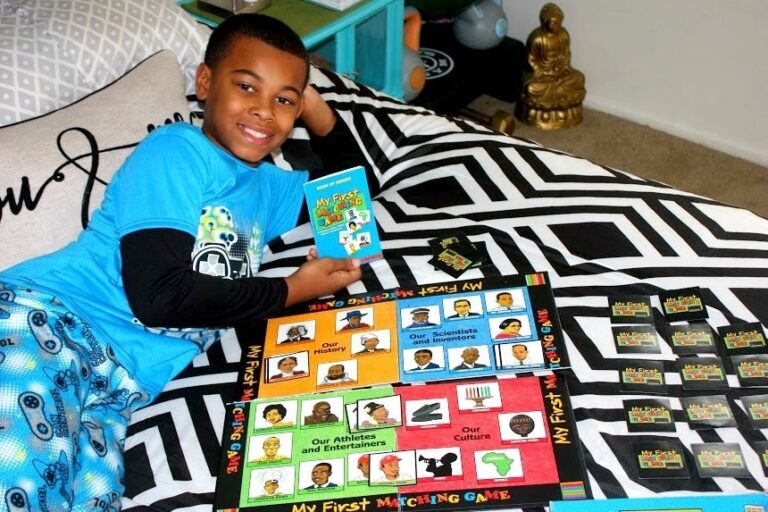

For nearly a decade, Hightower, who is Black, has made it her mission to provide the Black history her sons were not getting in school. She was initially inspired by a game she found in the clearance section of a Walmart while traveling years ago.

“It was a ‘my first matching game.’ It was a memory game about African Americans,” Hightower says. “And so, at that moment, that’s when I realized, like, I needed to be teaching them more at home about Black history.”

Hightower now has a collection of books and movies that her family revisits regularly.

In addition, every February, the family travels somewhere that has Black historical significance; they’ve visited the National Museum of African-American History in Washington, D.C., famed boxer Muhammad Ali’s childhood home — which is now a museum — and the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center in Cincinnati, among many other historical destinations.

“As a parent, I have to be proactive and make sure that they’re getting another perspective as well. Because, if I don’t do it, who’s going to do it?” Hightower says.

Illinois has new landmark legislation that aims to dismantle systemic racism in education. One part of this new law requires expanded Black history lessons in schools. This change is celebrated by Black teachers and parents, but some are concerned about how it will play out in practice.

The Illinois Legislative Black Caucus championed the legislation, which was signed into law by Gov. J.B. Pritzker in March. One part of the new law requires that schools teach an expanded version of Black history. Lessons should include the period that pre-dates enslavement dating back to 3,000 BCE, the reasons for slavery and the American Civil Rights Movement. Previously, Illinois mandated Black history instruction including the African slave trade, slavery in America and the vestiges of slavery in the U.S. — but specified no other time periods.

State Rep. La Shawn K. Ford, a Democrat and member of the Illinois Black Caucus, says he was motivated to pass the legislation because the history taught in schools today is inaccurate and biased toward Eurocentric and white perspectives of historical events. Ford is a former social studies teacher and he represents portions of Chicago’s West Side and western suburbs.

“I believe that when history was written, it was written with only one group at the table: white men. And so I think that this is not an attack on white men. This is just getting it right, realizing that it’s from one lens. And we want to fix that,” Ford says.

He says it was deeply important to him that the legislation mandate instruction about events that took place prior to the African slave trade. Ford says most instruction on Black history begins with slavery, which sends the message to students that Black people have always been oppressed and their contributions to society are limited to the fight to end that oppression.

“But the truth is, we were born in a country where we were kings and queens, where we had communities and culture. And we actually made major contributions to our country. And then we were uprooted, taken away from a culture. And our history was erased,” Ford says.

The new law also requires the creation of a 22-member “Inclusive American History Commission,” that will review available educational resources that reflect racial and ethnic diversity; provide guidance for the new learning standards and help educators ensure their instruction and content is not biased to value specific cultures, time periods and experiences. The commission will also develop guidance and tools to help educators locate and use resources for non-dominant cultural narratives and sources of historical information.

The commission will have members appointed by state politicians and the state superintendent of education. The group will include teachers, history scholars, a librarian, a principal, a superintendent, a school board member, in addition to educators who represent different regions of the state. A member of the Illinois State Board of Education (ISBE) will serve as the commission’s chairperson, and the commission is also required to submit a report about its work by the end of this year to ISBE, the governor and the General Assembly. At that point, the commission will be dissolved.

After updated social science standards are adopted, ISBE says the agency will work with districts to ensure “they are implementing these revised standards with fidelity,” Max Weiss, a spokesperson for the agency wrote via email. Weiss wrote that regional offices of education are responsible for monitoring compliance with state regulations. Teachers, however, are held accountable by their school districts through performance evaluations, Weiss wrote.

Ford says he’s been working on this legislation for years, but the killing of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor and the spotlight on racial inequities created an opportunity to get the bill passed.

Ford says he hasn’t heard any pushback on the new law, on the contrary, he says it’s been praised. He says there’s a growing realization that the history currently taught in schools is not healthy for a democracy.

“If we want to heal Illinois, then people have to know the truth: the good, the bad, and ugly. It’s what history is. History is not supposed to make you feel good. It’s supposed to teach you,” Ford says.

How will it work in the classroom

LaGarrett King, a professor and director of the Carter Center for K-12 Black History Education at the University of Missouri, applauds the expanded Black history legislation in Illinois. But he says the success of this new law will depend on how the instruction is implemented.

He applauds the Illinois legislation for including the experiences and histories of Black people before the slave trade began. But he says best practices for Black history education would also include:

- Moments of Black joy, “that you can still experience joy through notions of oppression without trivializing notions of oppression.”

- The contributions of Black women and Black LGBTQ individuals.

- The concept that Black excellence isn’t exceptional but commonplace.

- Black people who are currently making history and what the future will look like.

- And the notion of “Black historical contention,” which critically examines historical events and figures without glossing over their flaws.

“Sometimes when we present Black history, we overcompensate for the lack of Black history. So what we do is we present Black history as too pristine and too perfect,” King said. “When you present a Black issue that’s too perfect, what you do is you dehumanize those people, you dehumanize [Martin Luther] King, you dehumanize [Malcolm] X, without presenting a clear picture of who these particular people are.”

King also questions who will hold schools and teachers accountable for teaching Black history, and whether schools will receive the resources they need to do the subject justice. The new law does not include any additional funding for curricula or professional development.

“To effectively teach Black history, we have to teach Black history through Black perspective, and not the perspectives of white folk who teach about it, like what they imagine Black people to be and they want Black people to be,” King says.

About 82% of Illinois’ teachers are white, and only about 6% are Black. King says white people can teach Black history, but they need to do some “identity work” first. He says educators need to understand that “white people are just not that historically important.”

“At the end of the day, you can have the best curriculum, but if you have a teacher that still believes that white people are the center of history, then that curriculum means nothing,” King said.

Teaching Black history more accurately

Some schools in Illinois already teach an expanded version of Black history. Traevon Parnell teaches African-American history — an elective course — at Central High School in Champaign.

“I mean, we get an entire semester to really break down exactly why are Black people here? And what was the reason? What was the cause? And what enfranchisement has looked like over the last almost 170 years,” Parnell says.

Parnell, who is Black, says what he teaches students now is vastly different from the history curriculum he received in high school fewer than 10 years ago.

Like King, Parnell is pleased with the new law. But he also worries about how the material will be taught.

“There’s certainly a much more robust way of discussing the serious complexities of structural racism in this story of Black people. And there is really a wrong way to do it. And if you aren’t allocating enough effort, material, funding to it, which some schools might not be able to do, you know, what are you really expecting them to achieve in terms of dismantling the structures of racism and being anti-racist?”

Despite his concerns about how teachers will handle this mandate, Parnell says the law sets a standard for a new normal. And he is hopeful that students who are just entering public education will have a much more accurate understanding of history by the time they leave the K-12 system.

Brennon Hightower, the parent of two young Black boys in Danville, is also happy with the new law, even though she says it’s long overdue. However, she’s going to continue providing Black history education at home.

“Because I don’t know how it’s going to be taught. I don’t know who’s going to be teaching it… and change is not easy for everyone.”

Lee Gaines is a reporter for Illinois Public Media.

Follow Lee Gaines on Twitter: @LeeVGaines