This is the second in a series of stories. Read the first story here.

CHARLESTON, Ill. – Brice Fritz was naked, strapped down to a chair in a jail cell when a staff member monitoring her via video delivered 80,000 volts of electricity through the stun cuff on her leg.

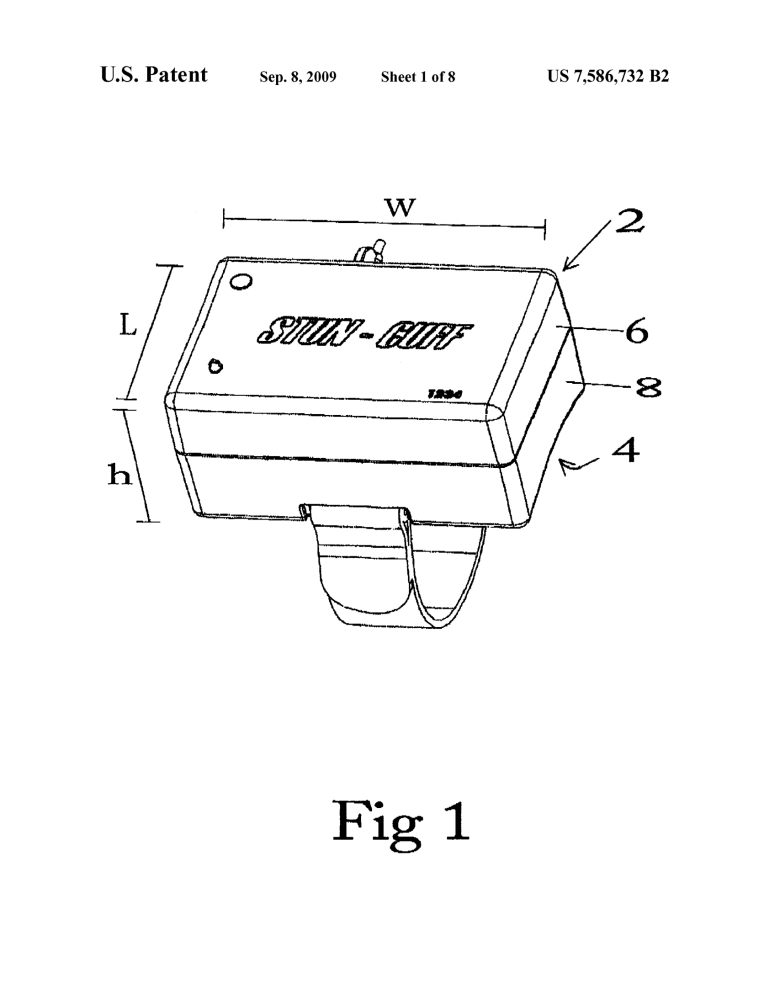

“I felt like I was being electrocuted,” Fritz told the Illinois Answers Project, recalling the incident at Coles County Jail in 2021. The cuff is a sort of shock collar for humans that the manufacturer describes as a wireless device to control detainees, typically used during court or transport.

Fritz, then 25, had been arrested on heroin and meth charges. She said she was in withdrawal that day, her period had started, she was bleeding, and jail staff did not allow her to shower.

She was on suicide watch, hitting her head repeatedly onto the ground, when staff put her in the chair with the cuff and stunned her, records show. She said the shock – which lasts five seconds and can leave burn marks – took her breath away and caused her to urinate on herself.

“When they stunned me, I felt like it lasted forever,” Fritz said. A standard police Taser, by comparison, issues 50,000 volts, and dog collars just a fraction of that. “I felt exposed and violated.”

Fritz is not alone. Other people endured similar treatment in the jail that year in this small eastern Illinois county.

A recent Illinois Answers Project investigation into the use of restraint chairs statewide found county jails used the devices more than a thousand times per year from 2019 to 2023. The investigation also identified a number of extreme incidents at Coles County Jail, which restrained people in chairs more than 200 times during that period and continues to use the device.

In multiple incidents, staff shocked someone with a stun cuff right before restraining them or right after releasing them. In others, staff kept a cuff on a restrained person but did not activate it. At least one other person was shocked with a cuff while restrained, one was stunned with a Taser while restrained, and one was stunned with a Taser while partially restrained.

In 2020, the jail restrained a man in a chair for the better part of 30 hours, until his hands and feet swelled, went cold and turned purple.

What’s more, Illinois Answers found Coles County failed to report some uses of a restraint chair to the state unit charged with overseeing jails.

The current sheriff, Kent Martin, attributes the issues to a vacuum of leadership under former Sheriff James Rankin, who resigned unexpectedly in early 2022 after eight years. Martin also points to the lack of medical and mental health resources both in and outside the jail.

At least two advocacy groups received complaints about Coles County Jail in 2020 and 2021 and issued reports finding the jail violated its own policies on restraint chairs and endangered people with disabilities. One warned the jail that its actions were unconstitutional.

In response, under Rankin’s leadership, the jail stopped using stun cuffs and pledged reform. Years later, Martin says he’s committed to those reforms. But an Illinois Answers investigation found that the jail has yet to live up to those promises.

“Without continued oversight, there just hasn’t been ongoing attention to these issues,” said Amanda Antholt, a managing attorney with Equip for Equality, a Chicago-based nonprofit watchdog.

Report found ‘grossly improper’ use of stun cuffs

In 2021, Equip for Equality investigated a complaint about Coles County Jail and concluded that staff responded to mental and behavioral health crises with excessive force and used restraint and seclusion as punishments in ways that posed “significant risk of harm,” according to a previously unpublished report obtained by Illinois Answers.

The nonprofit, which litigates civil rights cases, is mandated under federal law to monitor for abuse and neglect at Illinois facilities where there are people with disabilities, including mental illness. The group declined to say who filed the complaint, which is not public.

The group’s report – which included a site visit, interviews and a review of records – identified “routine uses of the restraint chairs as a control and punishment technique.” Due in part to the high ratio of detainees to officers, staff regularly used the chair in non-emergency situations, such as when inmates talked back, yelled or banged on a door, the report found.

“Detainees are restrained for periods in excess of therapeutic or security needs,” the report found. “That detainees are no longer a threat to themselves or others is evidenced by the detainee being able to leave the restraint chair to go to the toilet or being partially released to eat or drink.”

Daniel Lee Parks, 31, filed a federal civil rights lawsuit against Coles County officials in 2019, alleging he was restrained in a chair for three days. Parks, who has diagnosed mental illness and now receives treatment, said he was not properly medicated at the time.

“Instead of them trying to assist me, they would place me into a restraint chair,” Parks said, adding, “That would typically just get me more angrier.”

Parks settled his lawsuit for $1,000 after he couldn’t find an attorney, records show. Staff also placed a stun cuff on Parks at least once and shocked him with a Taser while trying to restrain him two other times, records show.

That fit a pattern. Equip for Equality found staff often deployed a Taser while forcing someone into a chair, attached a stun cuff “as an additional means of control or punishment,” and then “threatened” or “violently shocked” them with the cuff while restrained. The group received reports of detainees urinating, losing consciousness or having a seizure after being stunned.

Stun cuff policies posted online by the manufacturer advise staff to “use extreme caution and avoid standing near the suspect during its activation” and to take pictures of any subsequent burns.

From 2014 to 2021, the jail – with an average daily population of 100 detainees in that time – activated the devices more than 1,200 times, according to log entries generated each time a cuff is deployed, obtained by Illinois Answers. It is unclear how many of those incidents happened while someone was restrained.

Jail staff told Equip for Equality they used the devices on people in chairs when detainees attempted to loosen or remove straps, flip the chair or hit their head on the wall or furniture. “All these reasons indicate that the restraint chair is being used for inappropriate purposes and further mental health interventions are required,” the report concluded.

The group noted that being “deliberately indifferent to a substantial risk of serious harm” violates the detainee’s constitutional rights; and, restraining a person with mental illness, rather than finding appropriate treatment, may violate the Americans with Disabilities Act.

In Fritz’s case, staff placed the stun cuff on her left calf “in light of her continued attempts to free herself” from the chair, a county incident report states. Staff shocked her once, the report says.

More than an hour-and-a-half later, staff released Fritz from the chair and then removed the cuff, records show. She said she had marks from the electrodes on her leg for months. In its required report to the state, the jail detailed use of the chair but did not mention the stun cuff.

A month later, staff restrained a man in his 40s who had been hitting his head on the wall, and they placed a stun cuff on his leg. The man was rocking the chair back and forth and screaming “help me” when staff shocked him, records show. He was released an hour-and-a-half later.

Civil rights advocates, informed of the incidents by Illinois Answers, described the practice as torture. Daniel Sheline, president of the Illinois Correctional Association, the local chapter of the national trade association and accrediting body, called it “punishment.”

While a “large percentage” of the jail’s population had uncontrolled and worsening symptoms of mental illness and were experiencing drug and alcohol withdrawal, the jail had a “near-complete lack of psychiatric care” and no treatment for people in withdrawal, the Equip for Equality report found.

At the time, the jail contracted with Advanced Correctional Healthcare to provide a mental health professional for six hours per week. The report found the mental health professional did not routinely screen detainees for mental illness at booking, and even those with prior mental health treatment history at the jail were not identified for follow-up.

One person who disclosed their diagnoses of serious psychiatric conditions was not seen for over a month, and no psychiatric medications were prescribed for over two months even though the individual was “experiencing active delusions,” the report found.

Jessica Young, president and CEO of Advanced Correctional Healthcare, said she disagreed with some of the report’s findings. She said detainees are not required to be screened by a mental health provider during intake and that medical providers can use their discretion in issuing medications and determining next steps.

“The situation in Coles County has changed significantly since 2021 and numerous changes and improvements have been made,” she said.

The report also found jail staff routinely denied detainees access to previously prescribed medications for anxiety, sleep, and substance abuse disorders. Jail staff placed people in observation cells “for days to weeks at a time” where they had no access to water and “nowhere to relieve themselves except to urinate or defecate on the floor,” the report found.

Cory Barnes, 47, was restrained for more than seven-and-a-half hours in 2020 after he was arrested on charges of driving on a revoked license and possession of meth. Barnes said he’s struggled with mental illness since he was a boy and has long grappled with addiction. He has diagnosed bipolar disorder and a history of self-harm.

He refused to cooperate when officers were trying to move him from one cell to another, so they Tased him and put him in the chair. He said he sat for hours in his own urine, experienced cramps and screamed in pain.

“It’s a special kind of hell,” he said.

Restrained 30 hours, man’s hands and feet go cold

In 2020, Coles County Jail restrained a man for nearly 30 hours, records show.

That March, deputies from a neighboring county brought him in on suspicion of disorderly conduct, resisting and obstructing an officer, and attempting to disarm an officer, according to records. He stared at the wall for three hours before banging his head on it, leaving a bloodstain, records show. That’s when staff restrained him in the chair.

One of the officers texted the jail administrator and nurse to let them know what had happened, according to the reports. When officers tried to release the man later, he began hitting his head again, and the officers again restrained him, the reports said.

Staff attempted to remove him from the chair several times over the course of the next day, but he gave staff conflicting messages, saying he wished to be restrained and released. He rocked the chair back and forth and displayed “odd behavior,” the officers wrote.

When correctional officers checked on him the following morning, one observed that his “hands and feet were swollen and a purplish color.” Another said his hands “did not feel as warm as they should.” Jail staff then called the neighboring county to pick him up, and officers took the man to a nearby jail.

Dr. Marc Stern, who helped author guidelines for correctional healthcare and has monitored correctional facilities for the DOJ, said body tissues without circulation can be permanently damaged in approximately two hours and can die in four to six. If someone completely loses circulation for a few hours, he said, “the risk is losing your hands and feet.”

Following the incident, the Human Rights Authority of the Illinois Guardianship and Advocacy Commission, a state agency that advocates for people with disabilities, received a complaint alleging Coles County Jail staff do not follow policies on the use of restraints and do not notify medical staff when a patient is restrained.

It’s unclear who filed the complaint. The HRA denied a public records request for a copy of the complaint, and the man who was restrained and his family told Illinois Answers they did not file it.

The HRA interviewed jail employees, reviewed practices and policies and determined the jail violated state standards for county jails. Investigators reviewed the logs that staff use to document when they check on restrained people and allow them to stretch. The HRA found numerous gaps in the logs – up to six hours.

The unit charged with monitoring jails’ compliance – the Jail and Detention Standards Unit within the Illinois Department of Corrections – referenced the 30-hour incident in its annual inspection report, concluding jail staff are “relying on their own assessment of a detainee’s medical and mental health needs without seeking the review of a physician or mental health professional.”

The man who was restrained initially spoke with Illinois Answers but ultimately declined to be named for this story. His family, meanwhile, remains upset.

“He didn’t deserve that,” said his mother, who Illinois Answers is not identifying to protect her son’s identity. “Who do we hold responsible?”

Stun cuffs in storage after reforms recommended

Following the investigations, the advocacy groups recommended reforms to Coles County Jail.

The Human Rights Authority recommended Coles County re-train staff on the use of restraint chairs and how to check on restrained people; develop a policy on how to observe potentially suicidal inmates; and, date any new or updated polices to track changes.

Teresa Parks, director of the HRA, said the agency was “satisfied” with the response and negotiations with the jail following its investigation, so it did not refer the matter to the Jail and Detention Standards Unit for enforcement.

The jail declined to make its response public, which is allowed, Parks said. She did not detail the county’s response.

The following year, in 2021, Equip for Equality recommended the jail prohibit the use of stun cuffs, increase mental health staff, revise health screening protocols, curtail use of restraint chairs and limit their use to the shortest duration possible, among other reforms. The report said many of the jail’s challenges appear linked to “insufficient staffing levels – clinical and correctional – and deficiencies in the physical space.”

Antholt, of Equip for Equality, said the sheriff’s department took “really quick action on important steps,” such as stopping the use of stun cuffs, which the sheriff says are now in storage.

The jail pledged to retrain staff and improve mental health care, she said. Staff showed investigators architectural plans for a medical observation area in the facility, and, in initial follow-ups, reported a decline in use of force.

“That’s what they reported back to us, and those were all really, really good steps, I think, if they were followed through on,” Antholt said.

Equip for Equality has not returned to Coles County Jail since mid-2022.

Some action, but little progress

Since then, the jail has taken action on some recommendations but failed to make progress on others amid a change in leadership, Illinois Answers found.

Many of the most extreme incidents took place under the tenure of former Sheriff Rankin, who was elected in 2014 and resigned in early 2022, months before his term ended. At least nine other employees also left the department that year.

Martin was elected and took office in late 2022. He said he was unaware of the advocacy groups’ reports when first questioned by Illinois Answers.

Martin said that Rankin was frequently absent, so staff stopped soliciting his input and took matters into their own hands.

“There was kind of a void there in leadership,” Martin said, adding, “There wasn’t necessarily as much oversight as there should have been.”

Rankin did not respond to numerous requests for comment by phone, email and mail.

Martin said Coles County Jail staff may have been re-trained on the use of restraint chairs after the reports, but his office could provide no documentation.

In response to the HRA’s recommendation from late 2020, the jail created a policy specifically focused on how to observe possibly suicidal detainees, records show. But that didn’t happen until this past April. Previously, the jail had a general policy on inmate medical care that mentioned “suicide risk screening.”

The department has also added questions about mental health to intake and medical screening and plans to adopt a policy requiring mental health screening within two weeks of admission, he said. Sheline, of the Illinois Correctional Association, said it’s best practice for inmates to receive an initial mental health and medical screening upon admission.

Meanwhile, there’s been no new construction in the jail, and plans for a remodel are ongoing, which Antholt called “disappointing.” The remodel would include 10 double-occupancy medical cells, a shower area, a nurses exam area, and an area for corrections officers, Martin said.

The jail’s initial plans for a remodel were estimated at $792,000, records show. But bids for the project came in much higher, Martin said, so he has narrowed the plan, put out a new call for bids, and is looking for more money to “start the project.”

In the meantime, he said the jail has been using previously existing cells as “medical observation areas that are equipped with a toilet, in-cell camera, sink, and shower.”

In an April interview, Martin said the jail still only had a mental health professional for six hours per week, although he recently budgeted to bump that up to 12 hours.

“When they are here, they’re overburdened,” he said, adding that one inmate’s crisis can eat up most of the professional’s time.

The jail used to have a padded cell where staff would put someone in crisis, but the padding degraded and became unusable, he said. Martin said he is researching options on converting an existing cell into a padded cell and hopes to include a request for one in the next fiscal year budget.

“Without having a cash cow or a staffing explosion, I’m not sure what the best way is to handle that, frankly,” Martin said. “I think a padded cell may be helpful, so we could at least have a way to keep them from slamming their head into the concrete wall or the steel door, which really the only way we have right now for that is that chair.”

Reports missing as restraints continue

Even under new leadership, jail staff failed to report some restraint chair incidents to the Jail and Detention Standards Unit – the group within the Illinois Department of Corrections that monitors jails’ compliance with state standards.

Illinois Answers reviewed all reports submitted to the state but found no evidence showing that Coles County Jail staff submitted reports to the unit for more than a quarter of all incidents from 2019 through 2023, as required by administrative code.

Martin said he believes his staff submitted the reports to the state but may have misfiled them.

While the jail’s reporting to the state improved during the five-year period, there was still no evidence that multiple incidents last year were reported.

When the state did receive reports from the county, it’s unclear if anyone contacted the jail for follow-up or was aware of the improper use of restraint chairs and stun cuffs.

The IDOC said in an email that the state unit “makes every effort to ensure reports are reviewed individually and handled dependent on its content” and suggests improvements.

Brief mentions in the state’s annual inspection reports in 2020 and 2021 indicate the unit knew of the 30-hour incident and that the jail stopped using stun cuffs.

These same reports, along with the 2022 report, also cited the jail for not complying with state standards, finding insufficient staffing, officers not regularly checking on detainees, and problems with cell conditions and admission procedures. In 2023, the jail got a clean review.

Meanwhile, staff continued to restrain people in chairs dozens of times a year even after the advocacy groups’ reports. Staff used a chair at least 40 times in 2022 and 33 times in 2023, according to an Illinois Answers review of county records.

“For that small of a population to have that number of usages, it’s really concerning,” Antholt said.

Records show one person was restrained for half a day in late 2022, and, the following year, one person was restrained for more than six hours and another for nearly 11 hours.

A way forward for Coles County

Martin said he’s trying to professionalize and modernize the department and promote transparency.

He said he has emphasized with staff the importance of documentation and record-keeping. He implemented new software to electronically track cell checks and policy revisions, and he plans to send “daily training bulletins” to quiz his staff.

The department has also established a mentorship program with people from religious groups and a recovery program with a treatment center to address substance abuse issues.

In response to questions from Illinois Answers, Martin said that the department added restraint training to all quarterly training dates. Previously, restraint chair training “wasn’t as structured,” he said.

So far in 2024, jail staff have used the restraint chair at least 13 times and restrained one person at least four times, Martin said. That’s fewer instances at this point in the year than in prior years.

Asked why, Martin suggested that the state law eliminating cash bail beginning last September reduced the jail population and made it more manageable.

In 2021, the jail had 20 correctional officers and an average daily population of approximately 100 detainees, according to the county. Now, the jail has 21 correctional officers and a population closer to 78, the county said.

Martin said his jail and community face steep challenges. Part of the problem, he said, is that Coles County, a rural region in Central Illinois with a high poverty rate, generally lacks access to health care.

“It’s frustrating that we’re trying to do the best we can with what we have,” Martin said, “But the system or the state can do better.”

The Illinois Answers Project is interested in hearing from people who have been restrained in chairs. Reach out to reporter Grace Hauck at ghauck@illinoisanswers.org. Interested in localizing this story? Contact Mumina Mohamud at mmohamud@bettergov.org.

Edited by Rachel Aretakis and Casey Toner. Contributing: Cam Rodriguez and Laura Stewart, Illinois Answers Project. Database fact checking by Audrey Azzo, Doris Alvarez and John Volk.

Note on the methodology: There’s no clear definition of what constitutes a separate versus ongoing restraint chair “incident” in Illinois, where people are typically restrained in repeated two-hour blocks. For the purposes of this data collection and analysis, Illinois Answers considered an incident to be ongoing if someone was held continuously in a chair, or if they were only given brief and periodic breaks over a long period of restraint. In these cases, county jails often identified the case with a unique incident number, kept an ongoing observation log, and submitted a single, all-encompassing report to the state. Illinois Answers considered an incident as separate if someone was released from a chair for a prolonged period of time before being restrained again. In these cases, county jails often designated separate incident numbers, logs, and reports.

This story was made possible by a grant from The Richard H. Driehaus Foundation to the Illinois Answers Project.