Legislation and programs in states like Missouri and Nebraska are paving the way to welcome large livestock operations by limiting local control over the facilities. Some rural residents worry about the potential pollution and decreased quality of life that will bring.

CLARKSBURG, Mo. — In Cooper County, Missouri, CAFOs are a controversial topic.

Susan Williams asked to meet in a small local library to talk about it, hoping that there wouldn’t be anyone around. Even in this quiet atmosphere, she’s nervous about people overhearing the conversation.

“I just don’t want the whole town to hear me,” she said.

Listen to this story here.

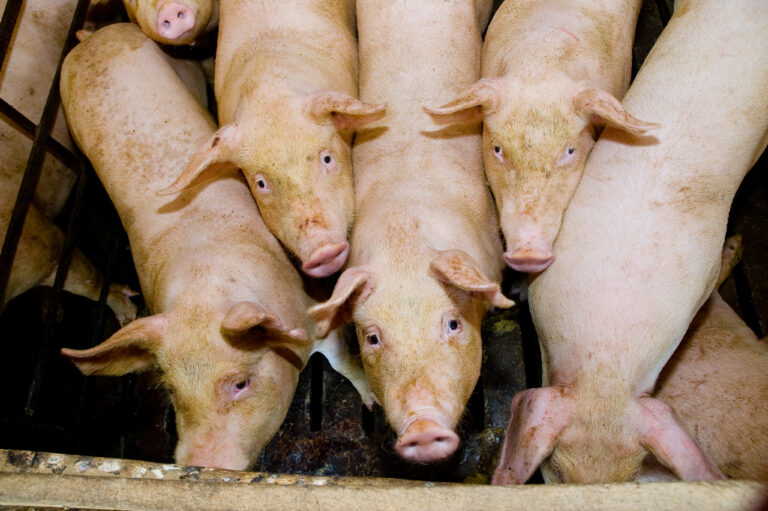

Concentrated animal feed operations, commonly called CAFOs, are large animal facilities that hold thousands of head of livestock. Iowa leads the Midwest in the number of CAFOs with about 4,000 of them. However, in recent years, laws and programs have paved the way for CAFOs to operate in other Midwestern states, including Missouri and Nebraska.

That’s worrying residents like Williams, a retired elementary school principal and a farmland owner from Clarksburg, Missouri. Back in 2018, a large hog operation called Tipton East planned on moving in less than a mile away from her house. The size of the operation, about 8,000 hogs, concerned her, especially since she grew up with a small hog farm.

“Just the smell and the waste that you had was tremendous with that,” she said. “And I couldn’t imagine what it would be like with that many hogs.”

Williams and some other residents brought their concerns — including what the operation would do to air and water quality — to the Cooper County Public Health Center. They were especially concerned about the waste the CAFO was going to produce, which was estimated in the facility’s application to be about 3.5 million gallons a year, and how it would be disposed of.

The company that owns Tipton East, PVC Management II, LLC did not respond to requests for comment.

Cooper County residents questioned whether the topography of the region would lead the waste to seep into the groundwater, since the manure would be spread on nearby fields. In response, the county health center created an ordinance to regulate emissions and the spread of manure from CAFOs.

But the next year, the Missouri Senate passed legislation preventing counties from enacting rules on CAFOs stricter than the state’s. Cooper County and Cedar County sued over the law and a subsequent house bill that tightened the language. A circuit court ruled in the state’s favor, so the counties appealed bringing the case straight to the Missouri Supreme Court, which has yet to issue a ruling.

Preventing local opposition

Laws that prevent local opposition to farm operations are common, said Loka Ashwood, a rural sociologist at the University of Kentucky.

“We see that across the country,” she said.

In 2022, the Iowa Supreme Court reversed a 2004 decision making it harder for landowners to sue CAFOs for damages. A small town in Wisconsin is currently being sued for passing an ordinance limiting pollution from CAFOs.

Every state also has some version of a “right-to-farm” law, which prevent individuals from filing nuisance suits against agricultural operations. Researching these laws, Ashwood and her colleagues found the most right-to-farm litigation is happening in the Midwest, and CAFOs are the most likely to win these lawsuits.

“In the Midwest, that's where people are fighting the hardest to try to defend their property rights, but they're also losing the most,” she said.

Welcoming agriculture

Some farm groups argue CAFOs can be an economic boon for rural communities and for the state.

Missouri Farmers Care, a group that wants to see agriculture grow in the state, has a program that designates counties with the title “agri-ready.” In order to receive that title, counties have to agree to a set of requirements that will make them more welcoming to farm businesses. Those requirements often include preventing or limiting additional restrictions on agricultural operations.

Mike Deering, who sits on the board of Missouri Farmers Care and is also the vice president of Missouri Cattlemen’s Association, said that CAFOs are a net-positive for the state.

“It's food security,” he said. “It's the food supply chain and to make sure that we are keeping that local and not having to import, import, import. And so we have to encourage growth.”

Ashlen Busick, a regional representative for the Socially Responsible Agriculture Project says programs like Missouri’s “agri-ready” designation are a way to deter counties from being able to implement health ordinances on CAFOS.

“One of the most important benefits of local control over CAFOs for the community is the ability for a community to determine its own practices that they would like the CAFO adhere to, to make sure they’re being protective of their community members,” she said.

In Nebraska, the state Department of Agriculture oversees a designation that is similar to agri-ready called “Livestock Friendly Counties.” The department will work with a county to develop zoning laws and permitting that makes it more accommodating to livestock production.

But according to Busick, welcoming CAFOs hurts small livestock producers.

“When the county is accommodating for the big ag industry, guess who continues to get pushed out of the market?” said Busick. “And guess who can hardly stand to live on their farms anymore because of the stench of the CAFOs just across the fence?”

Attracting operations

Recent studies done at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln have found livestock friendly counties don't have more livestock than other counties. Yet, one study found counties continue to join the livestock ready program.

Livestock friendly counties are more attractive for companies looking for places to build new CAFOs, according to the Nebraska Department of Agriculture.

“Companies looking to expand, or locate within Nebraska look for communities that would be welcoming to the project,” the department said in a statement.

Dodge County, Nebraska has the designation. Costco opened Lincoln Premium Poultry, a poultry plant there back in 2019. Jessica Kolterman, the plant’s director of administration, said Costco chose Nebraska in part because of the warm reception, in addition to the grain, water and workforce that the area provided.

“The other thing that they were really impressed with was the welcome they received from the state and the local government and also from the business leaders in the area,” she said.

‘The fight’s not ever going to be over’

Tipton East, the CAFO farm owner Susan Williams worried would move in, has been approved by the Missouri Department of Natural Resources but has yet to be built. While Williams waits for the CAFO and the Missouri Supreme Court to rule on whether local governments can regulate such operations, she has turned her attention to other methods of regulation.

She was among hundreds of residents and activists to give input into Missouri DNR’s new general permits for CAFOs. Missouri DNR held three public meetings in 2022 regarding the permits, and over 200 comments were sent in during the comment period. The new general permits now require CAFOs in Missouri to report where waste is exported, which will help both DNR and concerned residents address nutrient pollution.

Some environmental groups are also turning their attention toward the Environmental Protection Agency. In 2022 some organizations filed a lawsuit against the EPA for failing to respond to a 2017 petition asking it to revise the Clean Water Act’s regulations for CAFOs.

“We're trying to get some national fixes that would compel states like Iowa, Missouri and Nebraska that have demonstrated a lack of political will to regulate this industry to start doing so,” said Tarah Heinzen, the legal director of Iowa Food and Water Watch, one of the groups that filed the lawsuit.

With more attention surrounding CAFOs, Susan Williams holds onto a sense of optimism, as well as an understanding that the operations aren't going away anytime soon.

“The fight's not ever going to be over,” Williams said. “I think the public is always going to have to be vigilant to make sure that the public’s interests are taken into account just as much as any industry.”

Eva Tesfaye covers agriculture, food systems and rural issues for KCUR and Harvest Public Media and is a Report For America corps member. This story was produced in partnership with Harvest Public Media, a collaboration of public media newsrooms in the Midwest. It reports on food systems, agriculture and rural issues.