An interstellar comet is currently traveling through our solar system at 200 times the speed of sound. Astronomers around the world, including in Champaign-Urbana, are eager to see what the fast-moving space rock can teach us about the universe — and ourselves.

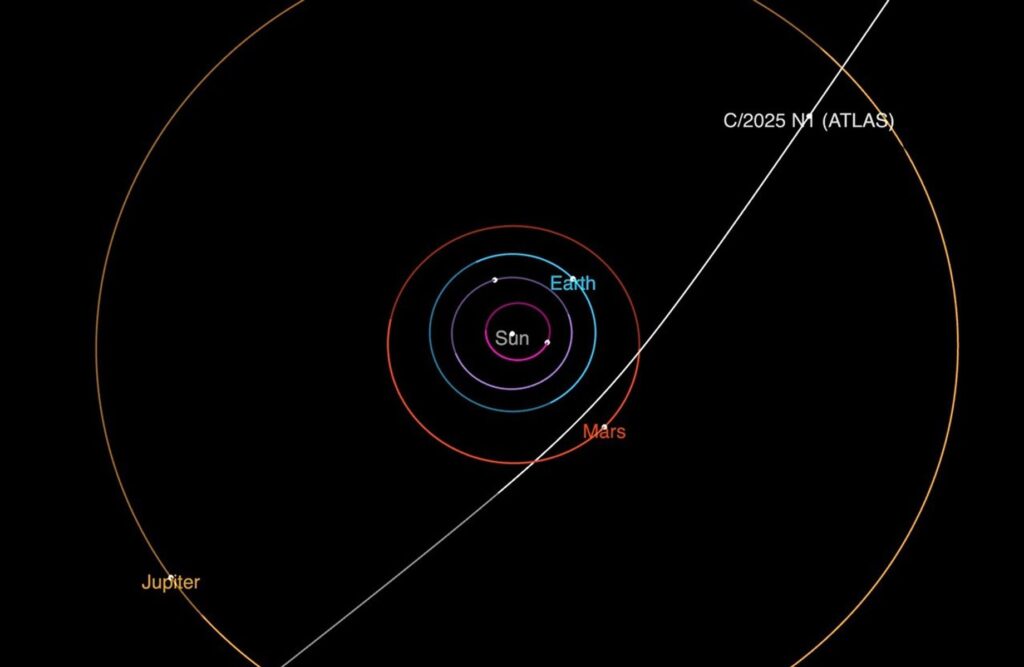

3I/ATLAS, the third observed interstellar object, will pass the Sun at the end of October, marking the start of the comet’s grand exit from the solar system.

Interstellar objects have hyperbolic trajectories, meaning they do not have a closed orbit around the Sun. It’s a limited-run show, soaking up the attention of space agencies and amateur astronomers alike before disappearing forever.

There’s a lot to be learned from this fast-moving space rock, said Aidan Berres, a fourth-year Ph.D. student in astronomy at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. He’s a data scientist interested in astronomical surveys — huge pictures of the sky that track an enormous amount of objects in space.

“Where is it coming from, where do we think it was made, or how old could it be?” he said. “These are all things that are pretty important when trying to figure out not only the origins of our solar system, but the origins of this kind of rock carbon material in the universe.”

Interstellar comets are free samples from beyond the solar system, delivered to us at remarkable speeds. They offer an opportunity to study the chemistry and geology of a place no one alive today will ever see.

This can provide insight into how our galaxy formed: How did gas and dust come together to form stars and planets? Do rocks form differently outside of our solar system?

“How does this impact the origins of us?” Berres said. “How did Earth form? How did our solar system form? If we can see that in other places, that is very impactful to find how did we get here.”

3I/ATLAS is moving even faster than the two interstellar objects that came before it: 1I/’Oumuamua in 2017 and 2I/Borisov in 2019. The Sun’s gravity increases this speed, so it will reach its maximum speed in our solar system in the last days of October, when it is closest to the Sun — a position known as perihelion.

At that point, the comet will be travelling at 42 miles per second relative to the Sun. For comparison, a car on a highway moves about 0.02 miles per second, and the speed of sound is about 0.21 miles per second.

Astronomers are interested in getting a closer look at interstellar comets, but their high speeds can be a challenge. Atsuhiro Yaginuma, an astronomy student at Michigan State University, who worked on one of the initial discovery papers for the comet, wrote a recent paper discussing the feasibility of sending spacecraft to do a fly-by with 3I/ATLAS.

“It was possible,” Yaginuma said in an interview. “Right now, it’s probably not.”

There was not enough time to prepare such a mission for 3I/ATLAS, which was first discovered in July. Current technology would not have allowed for spacecraft launched from Earth to reach the comet in time.

Yaginuma’s team’s calculations found a launch from Mars might have been feasible even after the initial discovery, if a mission had been ready to go.

But that doesn’t mean Yaginuma’s work was for nothing. He said the findings can be applied to future interstellar objects, as long as space agencies prepare further in advance.

He said details like the surface structure, spinning rate and tail of the comet could provide useful insight and would be easier to see by flying spacecraft close to the object.

“Hopefully in the future,” Yaginuma said.

Fortunately, more interstellar objects should reveal themselves soon enough.

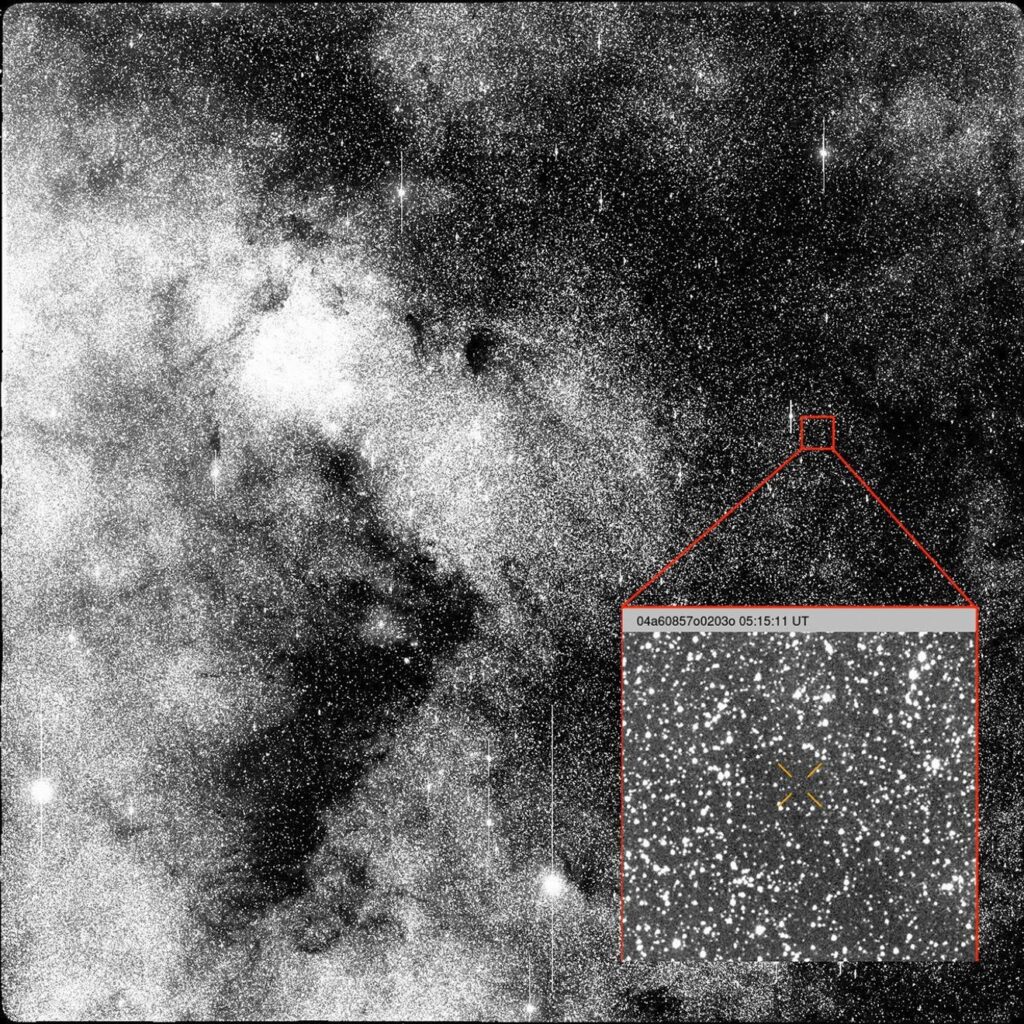

Berres said the Vera C. Rubin Observatory’s Legacy Survey of Space and Time is an example of modern observational technology improving scientists’ abilities to detect and study countless celestial objects. He has personal experience working with LSST data, studying the millions of asteroids the LSST tracks.

The LSST “is going to be scanning large portions of the sky periodically … for 10 years,” Berres said. “You’re definitely going to discover these new sources.”

Nowadays, with the massive quantities of data brought in by these large surveys, the initial detections are done by computers.

“This could never be done by a person or a team of people,” Berres said. “You have this automated pipeline that says, ‘These are new sources,’ and then those new sources, that table, gets given to interested scientists.”

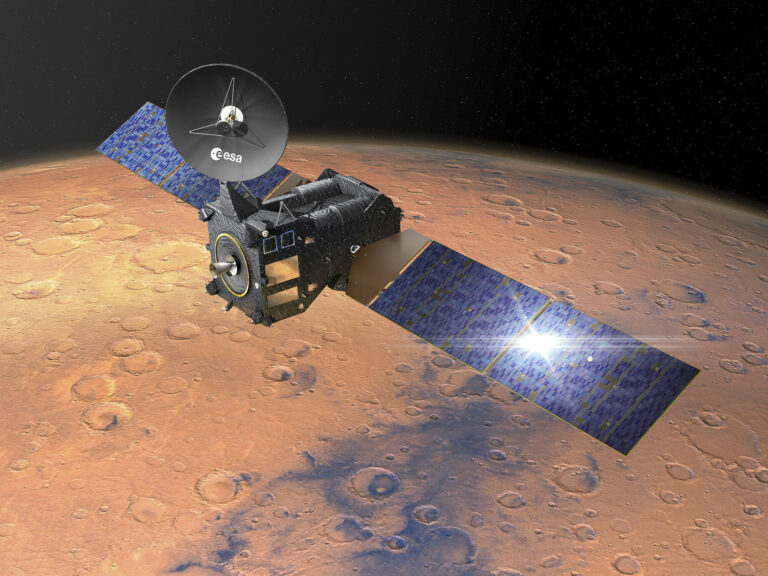

The European Space Agency is currently planning a Comet Interceptor mission that will stand at the ready for interstellar comets or comets from the outer solar system.

Once there’s a comet for the Comet Interceptor to target, it will move to an optimal position, deploy two probes and observe the comet from multiple angles as it passes.

The Comet Interceptor’s launch is planned for 2029. In the meantime, space agencies are working with what they have available.

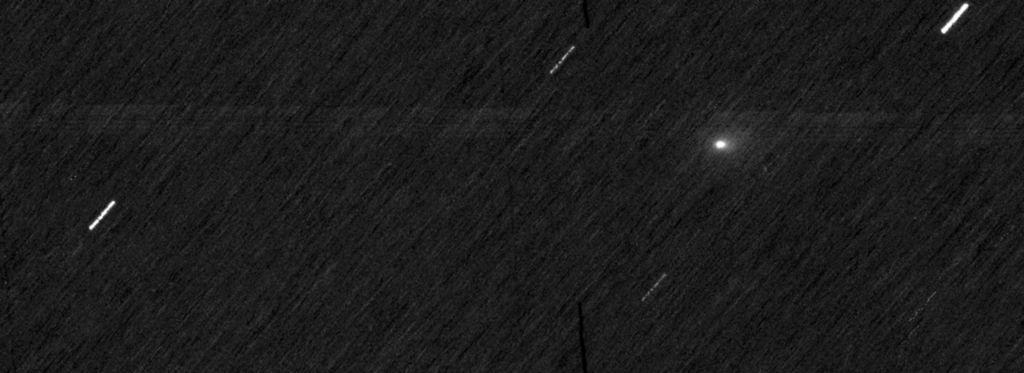

When 3I/ATLAS passed Mars in early October, the European Space Agency’s ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter and Mars Express observed it from about 18.6 million miles away. This distance is too far to make out the different parts of the comet, and the comet is much fainter than what the cameras are designed to capture. The ESA compared it to “seeing a mobile phone on the Moon from Earth.”

NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter and Perseverance rover were also expected to observe 3I/ATLAS. Whether that happened remains unknown, since the U.S. government shutdown has halted NASA’s communications. NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, which manages the orbiter and rover, did not respond to questions.

The ESA will continue to collect data on 3I/ATLAS as it continues its journey. NASA’s plans before the government shutdown was to do the same with over a dozen different assets, including the Europa Clipper launched last year.

Though the Sun blocks our view of the comet currently, it will be visible from Earth again by early December and will pass Jupiter in March. By next July, it will be passing Saturn, at which point it will be far too faint to see.