This story is a collaboration between Invisible Institute and IPM News

After fatal police shootings and other deaths at the hands of law enforcement in Illinois, investigating agencies are required to “publicly release a report” if no charges are brought against the officers.

The requirement was instituted as part of a broad police reform package passed in 2015 in the wake of the killing of Michael Brown by a police officer in Ferguson, Mo. The package included new mandates and regulations around chokeholds, stop-and-frisk, and body-worn cameras, the latter of which commanded the most attention at the time.

Around the time of its passage, news outlets also noted that many police killings or in-custody deaths were not publicly reported. Tucked into the 174-page law is a key provision intended to dictate how law enforcement and prosecuting agencies communicate to the public when police kill residents.

The provision states: “If the State’s Attorney, or a designated special prosecutor, determines there is no basis to prosecute the law enforcement officer involved in the officer-involved death, or if the law enforcement officer is not otherwise charged or indicted, the investigators shall publicly release a report.”

But regardless of intent, experts say vague wording in that single paragraph has resulted in a patchwork system across the state, leaving transparency to the discretion of local officials.

In most of Illinois’ largest counties — including Cook, DuPage, Lake, Kane, McHenry, Winnebago, Champaign, Sangamon, Peoria, McLean, Rock Island, and Kendall — prosecutors generally seem to comply with the law, releasing reports when they decide not to charge an officer.

In fact, of the 15 largest counties in Illinois, just three elected prosecutors appear to fail to meet this requirement: Will County State’s Attorney Jim Glasgow, Madison County State’s Attorney Thomas Haine and St. Clair County State’s Attorney James Gomric.

In Will County, in particular, there is little transparency — or consistency.

State’s Attorney Jim Glasgow, who has largely occupied the office since 1992, released letters with his legal conclusions in three recent deaths at the hands of police officers after the law was passed. Since the criminal justice reckoning in 2020, though, Glasgow seems to have shifted the responsibilities for publicly communicating findings about deaths at the hands of law enforcement from his office — run by an elected official — to the Will/Grundy Major Crimes Task Force, an obscure investigative body that only releases information upon request.

Despite being required under the law, Invisible Institute and IPM News could not find any evidence of his office reviewing an in-custody death at the Will County Adult Detention Facility.

The Task Force, made up of officers from agencies throughout Will and Grundy counties, has investigated police shootings since 2016, when the same law requiring a public report also mandated a third-party criminal investigation.

But the Task Force’s responsibility is to conduct a thorough investigation — not come to a legal conclusion about whether an officer violated the law when committing a fatal shooting or being involved in an in-custody death.

At least eight cases that would have received a detailed written legal review in other Illinois counties — if prosecutors did not bring criminal charges — have led to legal claims being filed. In one, the fatal shooting of Matthew Parks during a domestic disturbance response by Sgt. Terry Fenoglio, the Crest Hill City Council approved a $425,000 settlement with Parks’s widow this past February. That investigation did not involve interviewing Sgt. Fenoglio, Joliet Patch reported.

The Task Force’s practices fail to meet the standard of “publicly release[d]” reports, experts who spoke to Invisible Institute said. The only way for journalists and members of the public to obtain the reports is to file records requests, sometimes with multiple agencies. (There are also at least two cases that have been investigated by the Illinois State Police, not the task force — raising further questions after the ISP repeatedly refused to release documents or video footage from one because of the State’s Attorney’s Office’s extended review of the investigation. It’s not clear how decisions are made about when to bring in the ISP.)

Experts like Loren Jones, of the Chicago nonprofit Impact for Equity, say that the lack of transparency makes it unclear whether Will County government is fully complying with the law. She said the clearest path to making sure counties are following the law is to strengthen vague language in state law.

Will County’s inconsistencies are “extremely troubling,” Jones said. At the same time, the lack of clarity in the law, she said, makes it difficult to challenge an agency walking the line of meeting its “bare minimum” requirements.

Either way, the county’s practices end up leaving families of victims of police violence in the dark, said Trista Graves Brown, a Joliet activist and resident whose family friend, Jamal Smith, was killed by Joliet police in 2023. Police often say they can’t share information because of active investigations, she said.

“But how long is the investigation? A year? Two years?

“How long is it that you can never show the truth?” she asked. “How long does a family got to wait?”

Will County’s State’s Attorney, known as a “policeman’s prosecutor,” never charges on-duty police force or explains why

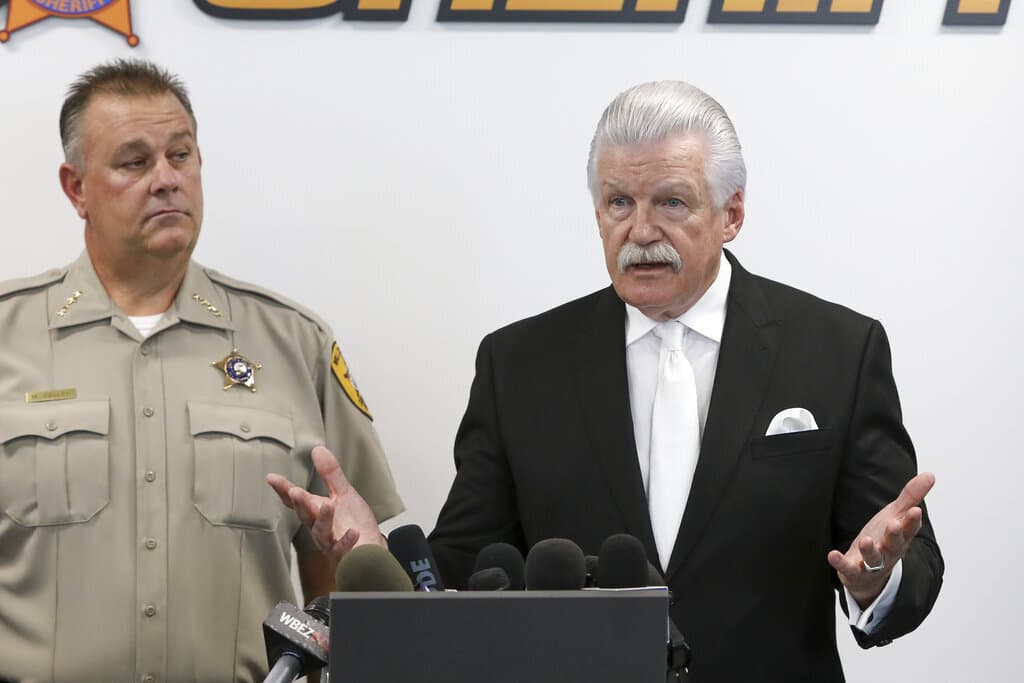

Over his three decades in office, Will County State’s Attorney James Glasgow has established himself as a law-and-order prosecutor — regularly trading on his prosecution of Drew Peterson, the former Bolingbrook police sergeant convicted of murdering one of his wives. (He was even the subject of an attempted hit by Peterson.)

It would be one of the only prosecutions of a police officer Glasgow ever filed; he has never filed charges against an officer in a police shooting or in-custody death.

Glasgow projects a tough image to the world. With a shock of thick white hair and matching mustache, and an endless supply of pinstripe suits with silk handkerchiefs, he looks almost out of central casting for an old-school tough-on-crime prosecutor. He was recently reelected to his seventh term — running unopposed.

“Will County is a very safe county,” he said during a June appearance on Chicago’s Morning Answer, a right-wing radio show. “We’re adjacent to Cook County, but we make certain that violent offenders know that they’re going to be subject to the prosecution that’s appropriate.”

In recent years, Glasgow publicly opposed criminal justice reforms at the state level, leading the charge of prosecutors around the state in unsuccessfully challenging the SAFE-T Act’s bail provisions — a hallmark of Illinois’ recent push for equity in its criminal justice system.

“He [is] a policeman’s prosecutor,” said Illinois Association of Chiefs of Police (ILACP) president Marc Maton, upon awarding Glasgow with the ILACP’s Public Official of the Year award in August. Maton is the chief of police of Lemont, which partially lies in Will County.

Maton added, “He is always on our side.”

Disparities in Public Reporting of Police-Related Deaths in Illinois

A review of the cases subject to the new reporting requirements since the law took effect in 2016 shows the wild variations in the level of information released to the public, and the shifting responsibilities as more scrutiny was directed to law enforcement.

Because no agency officially tracks all police shootings or other deaths at the hands of officers in Illinois, Invisible Institute reporters consulted with several sources to locate these cases: the limited records of the Will County State’s Attorney’s Office and Will/Grundy Major Crimes Task Force, local news reports, and two databases: the SPOTLITE database of police lethal force, maintained by the Cline Center for Advanced Social Research at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, and a dashboard maintained by the Illinois State Police, which is limited to cases involving ISP troopers, or when local agencies call on the ISP to investigate.

When 30-year-old Marcus Mays died at the Will County Adult Detention Facility in November 2018, a week after his arrest for an alleged battery during a psychiatric evaluation, his case became one of the first subject to the new requirements in Will County.

Mays, who had epilepsy, had informed the county’s private medical provider, Wellpath, of his condition when he was booked, according to a lawsuit filed by his estate. But both jail and medical employees failed to ensure that proper medications were on-site or schedule any medical appointments for Mays. On November 8, after a week of being off of his anti-seizure medications, he suffered a massive seizure in his jail cell and died.

By the next meeting of the Will/Grundy Major Crimes Task Force’s executive committee, on December 18, the case appears to have been closed. Buried in the “announcements” section of the meeting’s minutes is an oblique reference: “In-custody Death Investigation at WCADF – Apparent medical issue. No criminal charges.” It was the first reference to any such case in the committee’s minutes.

However, information about what happened to Mays has never been communicated to the public, even as the federal lawsuit brought by Mays’ estate has dragged on. The county has denied wrongdoing, but is taking part in ongoing settlement negotiations, according to filings.

And outside of two sentences in the task force’s meeting minutes, denoting that “no criminal charges” will be brought, there’s no evidence to show for the State’s Attorney’s Office’s review — let alone a publicly released report. Indeed, Torreya Hamilton, the attorney for Mays’s estate, said she was unfamiliar with any review the State’s Attorney’s Office conducted, and in response to a records request from Invisible Institute, the office stated that “no records have been located.”

The first “publicly release[d]” report wouldn’t come until the February 2019 fatal shooting of Bruce Carter Jr. by Joliet Police Detective Aaron Bandy, which resulted in an 11-page letter released 90 days later with Glasgow’s reasoning for not filing charges. Citing a “split-second decision” that Bandy claimed he had to make when Carter moved towards him with a box cutter, Glasgow found that Bandy did not violate state law.

It is the most detailed explanation Glasgow ever released.

Over the course of the three months between the release of his letter about Carter and the next fatal shooting, at least two more in-custody deaths at Will County’s jail — of Aaron Bowers and Jacob Adejola Sr. — would pass without a public ruling from Glasgow. His office said that no documents exist about those cases in response to a records request.

That next shooting occurred when Joliet Officer Ryan Killian killed Nakia Smith during a hostage standoff. However, Glasgow would not release his letter clearing Killian — this time just three full pages — until nearly a full year later.

After protests, Glasgow’s office stops publicly addressing police killings

In the time between Smith’s killing and Glasgow’s findings being released, two tragedies occurred. First, in January 2020, Eric Lurry died in the back seat of a Joliet Police car during a drug arrest.

The complete details of that case would not fully come to light until the second event occurred: the murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police in May 2020.

A month after George Floyd’s murder, the first allegations of misconduct in the Joliet Police’s involvement in Lurry’s death broke when longtime JPD Sgt. Javier Esqueda blew the whistle to the media and leaked dashcam footage to CBS Chicago. The video shows Joliet officers slapped Lurry after he had ingested some baggies of drugs, held his nose closed and put a baton in his mouth.

The day after the video’s publication, Glasgow released his public pronouncement on the case: two paragraphs clearing unnamed Joliet officers and blaming Lurry’s death on the “fatal levels of heroin, fentanyl, and cocaine in his system.” The finding led to protests at Glasgow’s office.

It would be Glasgow’s last public statement on a police killing. Since then, in the cases that have been subject to the requirement that a report be made public — fatal shootings, in-custody deaths, and other officer-involved deaths like those stemming from traffic pursuits — there has been silence from Glasgow and a shift of responsibility for public communication to the Will/Grundy Major Crimes Task Force and local police departments.

The next public communication would come in May 2021, about Joliet Police Officer Brian Lanton’s nonfatal shooting of Cordairel Whitmore, from Will County Sheriff’s Office Deputy Chief Dan Jungles, who ran the task force at the time. (It’s unclear why his office said anything at all; because the shooting was nonfatal, it was not actually subject to the public report requirement.)

Statements released by Jungles and Will County Assistant State’s Attorney Carole Cheney suggested that because charges had been filed against Whitmore and not Lanton, the public should infer that Lanton was cleared. The statements don’t directly address whether Glasgow had come to any legal conclusions about the shooting.

For the next three years, no public statements were made by the State’s Attorney’s Office, Task Force, or local police departments about the findings of any shootings or in-custody deaths. The silence continued until an article appeared in Joliet Patch in February 2024 about the fatal shooting of Victor Harris by Joliet police officers. Again, no report accompanied the story.

That story was published days after Invisible Institute sent questions to the State’s Attorney’s Office about whether it was complying with the legal requirement that reports must be “publicly release[d].”

Even with the release of information about Harris, at least 14 fatal police shootings or in-custody deaths in Will County have gone without any report or explanation about why law enforcement officers were not charged with a crime.

Those include fatal shootings by the Will County Sheriff’s Office and police departments in Joliet, Shorewood, Crest Hill, and Bolingbrook, and at least six deaths at the Will County Adult Detention Facility. The earliest of these cases occurred in April 2019.

When asked for records documentings the office’s findings about every police shooting since Glasgow first took office in 1992, the State’s Attorney’s Office was only able to provide a small handful of incomplete files: the letter clearing Brian Killian for killing Nakia Smith, a brief memo describing the fact that Cordairel Whitmore and not Lanton had been charged, and one-sentence emails to the task force clearing officers in three other cases.

Task Force and prosecutor pass the buck on transparency

Who maintains responsibility over the records of the Task Force —and the findings of the cases it investigates — also appears inconsistent. When Invisible Institute filed a request with the State’s Attorney’s Office for files from a particular 2020 case, the State’s Attorney’s Office released the Task Force’s investigatory reports, but no findings letter.

When asked again for that findings letter and two others in September, the SAO wrote in an email that the attorney who responded to the request “indicated that he had turned over everything he was able to locate.” The Joliet Police Department was also unable to provide any findings letter clearing its officer.

When asked months later whether the absence of the letter meant that the public reporting requirements of the Police and Community Relations Improvement Act were being violated, Assistant State’s Attorney Carole Cheney pointed to the presence of the word “investigators” in the text of the law. She argued this meant that their office was not accountable for the public release. She suggested that this fell under the purview of the Task Force, and directed further requests to the Task Force.

However, the bylaws of the Will/Grundy County Task Force clearly state that “the State’s Attorney’s Office of jurisdiction shall be responsible for FOIA compliance with regard to the task force and the investigation.”

When Commander Kevin McQuaid, the leader of the task force, received the new request after Invisible Institute was referred to the Task Force, he made clear that he did not have ultimate control of the records.

“I have received your email and have forwarded it to the Will County States Attorney’s Office for their review,” he wrote in response.

Five days later, he released the Task Force and SAO’s findings in the cases for the first time. The Task Force reports were each two pages, without legal analysis, and merely summarized aspects of the investigation.

The SAO’s official findings, sent to the Task Force’s commander, each consisted of one nearly identical sentence. “Based on a thorough review of” the case files, an assistant state’s attorney wrote, “there is no basis to prosecute the law enforcement officer in the officer-involved death.”

When asked if releasing records through FOIA complies with the public reporting requirement, neither McQuaid nor Cheney responded.

Jones, of Impact for Equity, said she doubts it. “It’s my understanding that if you are required to do a FOIA request to receive the information, it has not been publicly released,” she said. “It’s a public document, but it’s not publicly available.”

Vague language in Illinois law leaves questions about police reporting

Experts don’t expect much to change about the system in Illinois until the language in the law is clarified. That’s because it’s simply too vague and allows for wildly disparate interpretations of what information must be released and who is responsible, Jones said.

“The act mentions that the investigators are required to release the report. If there are no charges brought against the officers or there’s no indictment, it’s unclear what needs to be included in that report,” she said, adding that there aren’t even any guidelines around when these need to be released.

It’s unclear exactly what legislators meant by “the investigators shall publicly release a report.” The language was inserted in an amendment to an existing bill, and was not discussed during either the House Judiciary-Criminal Committee meeting where legislators approved the amendment or on the Senate floor, according to legislative records.

The plain text implies that the Task Force, and not the State’s Attorney’s Office, is responsible for the public release of the report, said Eileen Prescott, a law professor at Wake Forest University and director of its Accountable Prosecutor Project.

“This strikes me as inefficient,” she wrote in an email, “but the General Assembly may have meant to keep the investigators independent even from the State’s Attorney’s Office.”

Either way, she continued, the records released by the State’s Attorney’s Office and Task Force for cases after 2020 appear to comply with neither the spirit of the law, nor best practices for prosecutors. “As I read the statute, the report needs to provide enough detail to understand the basis for the decision not to prosecute,” she wrote.

“The report might not need to include legal conclusions, but it probably should include reasoning in favor of not taking further action, as well as the facts supporting that reasoning,” she continued.

“For example: How far away was the deceased? Were they armed? What were they doing in the moments before their death? Is there camera footage or other corroborating evidence beyond the accounts of the officers themselves?

“Given this context, I don’t believe that merely releasing an email that says ‘the SAO found no basis to prosecute the officer’ would comply with the report requirement.”

Neither Attorney General Kwame Raoul nor State Sen. Elgie Sims, Jr., who each carried the amendment while serving in the state Senate and House, respectively, responded to multiple requests for comment.

However, at least two other large prosecutor’s offices in Illinois have outlined exactly how they interpret the law. The Cook County State’s Attorney’s Office publishes the official policy of its Law Enforcement Accountability Division on its website. In the section about communications to the public, after discussing the legal limitations placed on public releases of information by various state and federal laws or rules, the State’s Attorney’s Office then outlines:

“At the conclusion of the investigation, if no criminal charges are brought, the Cook County State’s Attorney’s Office will post a memorandum on its website explaining the facts of the case, the legal principles involved, and the reasons for the decision.”

Similarly, the State’s Attorney’s Office in Winnebago County, based in Rockford, published a statement and FAQ document about its role in police shootings and in-custody deaths.

In it, the office writes, “If charges are not approved, the SAO will issue a public statement — a memorandum of decision — providing the facts and legal theories underlying the decision.”

These policies more closely align with national best practices pointed to by Prescott, including a 2019 toolkit from the Institute for Innovation in Prosecution at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice, which calls for prosecutors to publicly discuss their “decision, evidence, and rationale” for not charging an officer.

When presented with Invisible Institute’s findings, Will County Board Member Jacqueline Traynere, who leads the Democrats on the board, said in an interview that “transparency is important for people to see what’s going on,” and called for “a lot of transparency anytime an officer is involved in a shooting.”

The gaps, loopholes, and vague language in the law being utilized by bodies of Will County government point to a need for more legislation, Jones said. She compared the single paragraph about police killings and in-custody deaths to a requirement to report general uses of force that was passed in the 2021 SAFE-T Act. Local and state agencies are not yet fully compliant with the new law, but it provides far more specific benchmarks to hold them accountable.

The new use of force reporting requirements also came with enforcement power; the Illinois Law Enforcement Training and Standards Board can withhold funding if an agency fails to report fully or accurately. While this hasn’t happened yet, there’s still “a function there to spur people to report,” she said. “There is a mechanism in place that can be pulled and advocacy that can be done to change that.”

Without further legislation, she said, there will continue to be no real “parameters” around the true role and responsibility of prosecutors in communicating their decisions to not file charges when Illinoisans are killed by police or die in their custody. That ultimately leaves “sort of a dearth” of information in Will County, she continued — and “a gap for clarity, timeliness and transparency about officer-related deaths for the public.”

The same gaps exist in Madison and St. Clair counties, which border each other in the St. Louis Metro East region. At least six police shootings or other deaths in Madison County, and seven in St. Clair County, have occurred in recent years. Both counties have failed to publish any findings.

The Madison County State’s Attorney’s Office released hundreds of pages of findings letters for police shootings and in-custody deaths since 2019 upon request from Invisible Institute. It does not appear that any of them had been previously published.

By contrast, the St. Clair County State’s Attorney’s Office said it had no written policy for police killings or in-custody deaths and did not have any decisions in any such cases since 2019, when State’s Attorney James Gomric was first appointed in 2019 to replace Brendan Kelly, who was named director of the Illinois State Police by Gov. J.B. Pritzker.

After Invisible Institute asked for records about a particular case from 2021, the office denied the records, claiming they fell under protections for “deliberative” records. When an appeal was filed with the Attorney General’s office, the State’s Attorney’s Office provided a one-page letter clearing officers. An appeal is pending seeking further cases.

Requests for comment sent to both the Madison and St. Clair State’s Attorney’s Offices about whether they consider themselves in compliance with the law requiring “publicly release[d] reports” went unreturned.

If an officer is being cleared for their fatal shooting or involvement in an in-custody death, “they should never have a problem exposing who did it, why they did it, and how they did it — because they did it,” said Trista Graves Brown, the family friend of Jamal Smith, who was killed by Joliet Police last year.

“If you have nothing to hide, you shouldn’t have a problem with that.”

This story was produced in collaboration between Invisible Institute, a nonprofit public accountability journalism organization based in Chicago, and Illinois Public Media News, the NPR/PBS member station based in Champaign-Urbana. It was supported by the Data-Driven Reporting Project, which is funded by the Google News Initiative in partnership with Northwestern University | Medill; and by the University of Vermont Center for Community News.

Sam Stecklow is an investigative journalist and FOIA fellow with Invisible Institute. Follow him on Bluesky at @samstecklow.bsky.social or Twitter at @samstecklow, or email him at sam@invisibleinstitute.com.

Chris Weber is a freelance journalist and graduate student. He reported this story as an investigative reporting intern with Invisible Institute through the Governors State University Center for Community Media.