On a recent Monday morning, a group of preschoolers filed into the gymnasium at Hillside School in the west Chicago suburbs. These 4- and 5-year olds were the first of more than 200 students to get tested for the coronavirus that day — and every Monday — for the foreseeable future.

At the front of the line, a girl in a unicorn headband and sparkly pink skirt clutched a plastic zip-top bag with her name on it. She pulled out a plastic tube with a small funnel attached, and was then led by Hillside superintendent Kevin Suchinski to a spot marked off with red tape.

Suchinski had her sit down while he coached her how to carefully release — but not “spit,” which could get messy — about a half teaspoon’s worth of saliva into the tube.

“You wait a second, you build up your saliva,” he told her. “You don’t talk, you think about pizza, hamburgers, french fries, ice cream. And you drop it right in there, okay?”

The results will come back within 24 hours. Any students who test positive are instructed to isolate, and the school nurse and administrative staff carry out contact tracing.

Hillside was among the first in Illinois to start regular testing. Now, almost half of Illinois’ two million K-through-12 students attend schools rolling out similar programs. It’s all supported by federal funding that’s being channeled through the state health department.

Schools in other states — like Massachusetts, Maryland, New York and Colorado — are also offering regular testing; Los Angeles public schools have gone further by making it mandatory.

These efforts stand in pretty sharp contrast to states where people are still fighting about basic things like wearing masks in the classroom. Schools without mask mandates have experienced outbreaks and even teacher deaths.

Within a few weeks of schools reopening, tens of thousands of students across the U.S. were sent home to quarantine. It’s a concern because options for K-12 students in quarantine are all over the map — with some schools offering virtual instruction and others providing little or no at-home options.

Suchinski hopes this investment in testing prevents Hillside school from spreading the virus — and keeps kids learning.

“What we say to ourselves is: If we don’t do this program, we could be losing instruction because we’ve had to close down the school,” he says.

Avoiding Zoom school at all costs

So far, the parents and guardians of two-thirds of all Hillside students have consented to testing. Suchinski says the school is working hard to get the remaining families on board by educating them about the importance — and benefit — of regular testing.

Every school that can manage it should consider testing students weekly — even twice a week, if possible, says Becky Smith. She’s an epidemiologist at the University of Illinois in Urbana-Champaign, which invented the saliva test Hillside and other Illinois schools are using.

Smith points to several studies — including both peer-reviewed and preliminary research — that suggest rigorous testing and contact tracing are key to keeping the virus at bay in K-12 schools.

“If you’re lucky, you can get away without doing testing, [if] nobody comes to school with a raging infection and takes their mask off at lunchtime and infects everybody sitting at the table with them,” Smith says. “But relying on luck isn’t what we like to do.”

Julian Hernandez, a Hillside seventh grader, says he feels safer knowing that classmates infected with the virus will be prevented from spreading it to others.

“One of my friends — he got it a couple months ago while we was in school,” Hernandez recalls. “[He] and his brother had to go back home… They were okay. They only had mild symptoms.”

Brandon Muñoz, who’s in the fifth grade, says he’s glad to get tested because he’s too young for the vaccine — and he really doesn’t want to go back to Zoom school.

“Because I wanna really meet more people and friends and just not stay on the computer for too long,” Muñoz explains.

Suchinski, the superintendent, says Hillside also improved ventilation throughout the building, installing a new HVAC system and windows with screens in the cafeteria to bring more fresh air in the building.

Regular testing is an added layer of protection, though not the only thing Hillside is relying on: About 90% of Hillside staff are vaccinated, Suchinski says, and students and staff also wear masks.

Setting up testing with outside advice — and funding

Setting up a regular mass testing program inside a K-12 school takes a good amount of coordination, which Suchinski can vouch for.

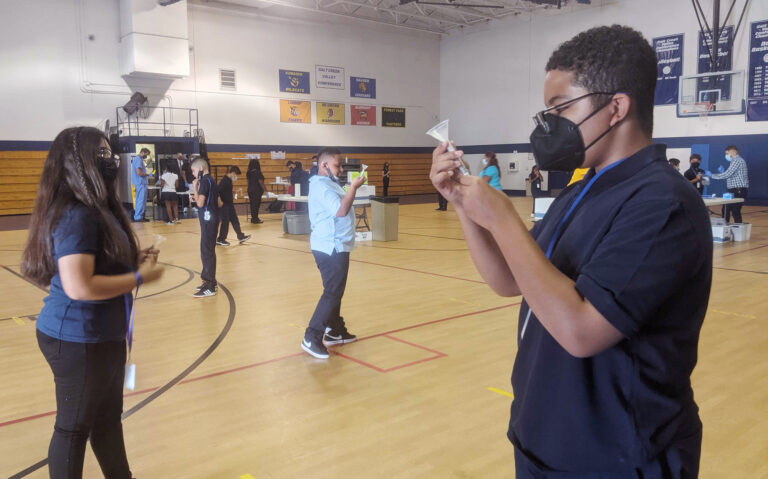

Last school year, Hillside school administrators facilitated all the saliva sample collection without outside help. This year, the school tapped funding earmarked for K-12 coronavirus testing to hire COVID testers — who coordinate all the logistics of collecting, transporting and processing samples, and reporting results.

A couple Hillside administrators help oversee the process on Mondays, and also facilitate testing for staff, plus a twice-a-week testing other days for a limited group of students. Athletes and children in band and extracurriculars test twice a week because they face greater risks of exposure to the virus from these activities.

Compared to a year ago, COVID testing is now both more affordable and much less invasive, says Mara Aspinall, who studies biomedical testing at Arizona State University. There’s also more help to cover costs.

“The Biden administration has allocated $11 billion to different programs for testing,” Aspinall says. “There should be no school — public, private or charter — that can’t access that money for testing.”

Creating a mass testing program from scratch is a big lift. But more than half of all states have announced programs to help schools access the money and handle the logistics.

If every school tested every student once a week, the $11 billion earmarked for testing would likely run out in a couple months. (This assumes $20 to buy and process each test, a cost estimate approved by Aspinall.)

Put another way, if a quarter of all U.S. schools tested students weekly, the funds could last the rest of the school year, Aspinall says.

Schools must weigh the benefits and costs of testing

While rapid antigen tests can cost less than PCR tests and provide results faster, they’re less reliable for people who are not showing symptoms, says epidemiologist Becky Smith.

Highly sensitive saliva-based PCR tests can help identify people before they become infectious. But the person might not get results until the next day. So Smith says she advises schools to use a combination of the two.

For example, schools implementing “test to stay” protocols — in which students who’ve been exposed to the coronavirus at school are allowed to continue with in-person learning as long as they receive a negative test result every other day for a full week after exposure — can alternate between rapid tests and PCR tests.

In its guidance to K-12 schools, updated on Aug. 5, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention does not make a firm recommendation for this surveillance testing.

Instead, the CDC advises schools that choose to offer testing to work with public health officials to determine a suitable approach, given rates of community transmission and other factors.

Administrators are advised to choose tests that provide results within 24 hours. If testing cannot be conducted in schools safely — and meet other criteria outlined in the guidelines — the agency recommends schools refer students and staff to community-based testing sites.

“The benefits of school-based testing need to be weighed against the costs, inconvenience, and feasibility of such programs to both schools and families,” the current guidance states.

The agency previously recommended screening testing at least once a week in all areas experiencing moderate to high levels of community transmission. As of Sept. 15, that included 98% of U.S. counties.

For school leaders looking to explore their options, Aspinall suggests a resource she helped write, which is cited within the CDC guidance to schools: the Rockefeller Foundation’s National Testing Action Plan.

The document includes a detailed summary of successful K-12 COVID testing programs across the U.S. — and a checklist for school administrators evaluating proposals from testing vendors.

If a school is weak in one area — like mask-wearing or keeping students in small groups or pods — school leaders should consider strengthening other areas, Smith says.

Vaccines are particularly important, as high levels of protection among adults and older children can help protect kids under 12 who are not yet eligible for the vaccine.

“On the other hand, at this point schools are already open,” she says. “And it’s a lot faster to get a testing protocol in place than to get everybody fully vaccinated.”

Taking action and hoping for the best

This spring — when Hillside was operating at about half capacity and before the more contagious Delta variant took over — the school identified 13 positive cases among students and staff via its weekly testing program.

The overall positivity rate of about half a percent made some wonder if all that testing was necessary.

But Suchinski says that by identifying the 13 positive cases, the school perhaps avoided more than a dozen potential outbreaks. Some of the positive cases were among people who weren’t showing symptoms but still could’ve spread the virus.

“Some [other superintendents] are worried that if they do the testing, they would catch asymptomatic kids,” he says. “And what I said is: ‘So what? That’s what we want to do, right?’ We want to keep it out.”

A couple weeks into the new school year at Hillside, operating at full capacity, Suchinski says the excitement is palpable.

Nowadays, he says he’s balancing feelings of optimism with caution.

“It is great to hear kids laughing. It’s great to see kids on playgrounds,” Suchinski says.

“At the same time,” he adds, “we know that we’re still fighting against the Delta variant and we have to keep our guard up.”

This story comes from NPR’s health reporting partnership with Illinois Public Media, Side Effects Public Media, and Kaiser Health News (KHN).