Across the United States, there’s a push to give new doctors cultural training to work with refugees and other immigrants. And some say it’s the difference between healthy and sick patients.

On a block on Indianapolis’ southside, there are three international grocery stores — Saraga international grocery, Tienda Morelos and Chinland Asian Grocery.

This area once was almost all-white and hostile to minorities, according to a newspaper clipping from 1965. Now, a community of Burmese refugees, along with a growing subset of Congolese and Syrian refugees, call this southside suburb home.

And down the road is the Franciscan Health Family Medicine Center.

“So we have our underserved southside population, and then we also have a significant amount of immigrants and refugees,” says Adam Paarlberg, a family medicine doctor at Franciscan Health.

Paarlberg also trains medical residents who help staff this clinic.

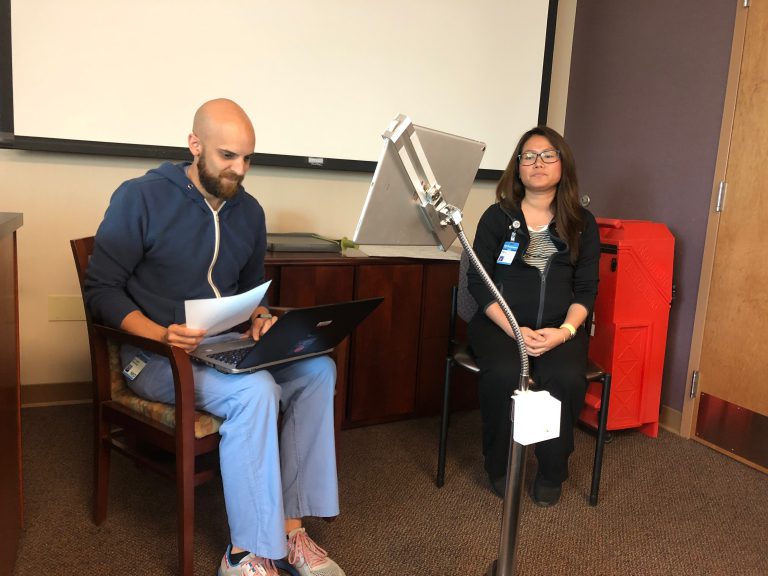

On a late summer day, around two dozen of these residents are watching a demonstration of a translation system call Martti. It looks like an iPad on a rolling stand, and connects doctors with live interpreters for over 250 languages.

At the front of the room, Paarlberg and a medical assistant are staging an exam as part of the training session. The Martti interpreter translates his words into Hakha Chin, a regional dialect in Myanmar.

“If she’s having any headaches, dyspnea, right upper quandrent pain, edema … Probably needs to come to the triage, but we’ll see her next week.”

The residents laugh because Paarlberg intentionally demonstrated some of the don’ts of working with an interpreter. He asked long, rambling questions and used confusing medical jargon.

“”As you can imagine telling the patient to ‘break a leg,’ or you know, ‘this is going to cost you an arm and a leg’ there might not be an equivalent there,” Paarlberg tells the residents.

Second-year resident Michael Padilla says the demonstration made him more aware of the complexity of translations.

“Like one of the things that we learned today that was really cool was is there’s no word for anxiety,” Padilla says. “And how some things get translated like ‘how you got here’ was turned into ‘how did you make this appointment.'”

But this training is about cultural considerations too. Like knowing how to address mental illness — a condition seen as taboo in some cultures.

Paarlberg says patients may complain of physical symptoms instead. “They may come in with a headache or abdominal pain, or dizziness, or something like that.”

This means mental illness can go undiagnosed unless a doctor understands cultural clues. Paarlberg says training residents to be aware of these considerations is more than just being polite.

“If a patient doesn’t feel like that you’re being mindful or understanding or culturally sensitive, meaning you’ve already lost that person,” he says. “That person’s not going to follow your instructions, they’re not going to be compliant with the medical care and follow up.”

David Acosta, Diversity Director with the Association of American Medical Colleges, says more medical schools are offering this type of training.

“This new generation has a large interest in getting these experiences, and so medical schools basically are really pushing hard to try to provide those experiences to them,” Acosta says.

Of the medical schools the association surveys, more than 60 percent now offer training on cultural competency. This is up from just 30 percent several years ago.

Paarlberg says preparing future doctors to work with people from different cultures isn’t just for big cities anymore. Even rural hospitals need it.

This story was produced by Side Effects Public Media, a news collaborative covering public health.