Deli meats, carrots and fast food onions are some of the products that were recently recalled across the U.S. Experts say improved detection strategies means regulators are able to catch more health risks.

Millions of pounds of food have been pulled off of shelves across the country in recent months due to health concerns.

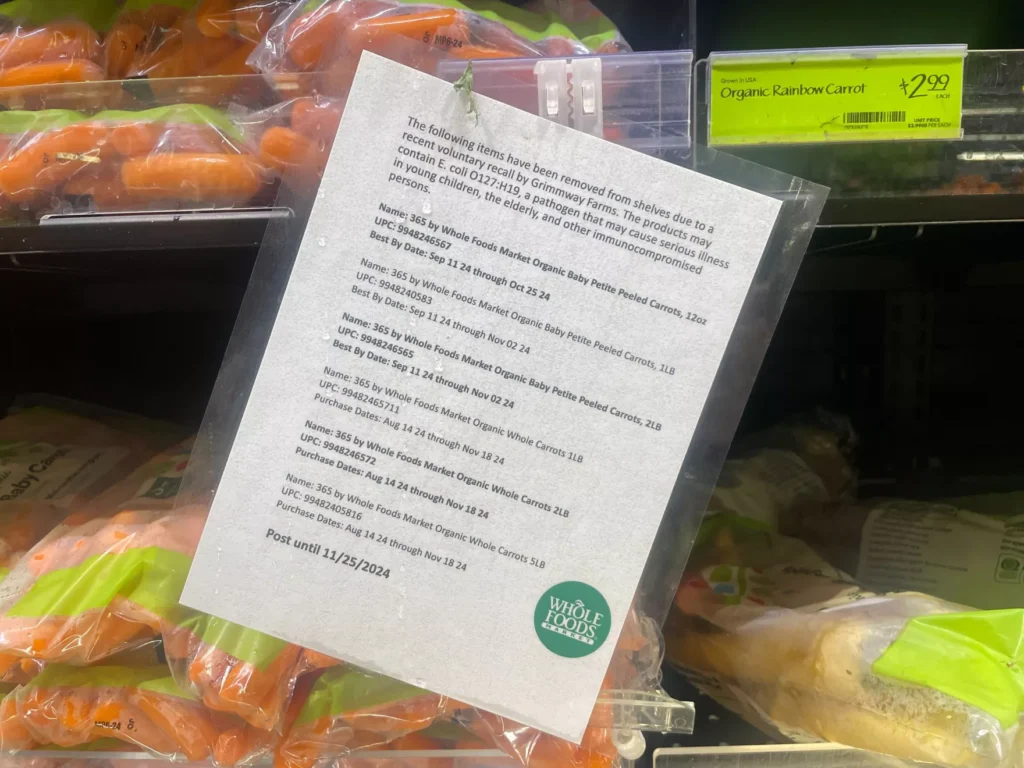

The recalls include E. coli tied to specific produce and listeria connected to different meat products.

In October, Oregon-based company BrucePac, recalled about 11.7 million pounds of ready-to-eat meat and poultry products from its Oklahoma facility because they might be infected with listeria. No confirmed reports of adverse reactions have been reported, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture Food Safety Inspection Service (FSIS).

Earlier this year, Boar’s Head recalled 71 products over listeria concerns. On Thursday, health officials announced the Listeria outbreak tied to the recall is over. Ten people died and 61 people got sick in 19 states, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

There have also been several brands of bagged carrots removed from shelves due to E. coli in an ongoing recall, and the company that produces the slivered onions for McDonald’s Quarter Pounders issued a recall in October. There is at least one death reported for each of these cases.

Food is pulled for reasons that could cause illness or injury, like when it’s contaminated or mislabeled. To prevent recalls, there are multiple safeguards in place that span from growers in the field to government regulators.

Abby Snyder, a professor of microbial food safety at Cornell University, said these recent large recalls do not reflect a change in the overall safety of the food supply. Over the past 20 years, U.S. food agencies have gotten better at detecting bacteria in food, she said.

“That’s why we’re able to recognize even relatively small outbreaks now due to the improvements on the disease surveillance side,” Snyder said.

She said large recalls happen occasionally, largely because of unintended food safety failures – and sometimes that means several recalls.

“We’re just in a period where several seem to have happened in a relatively short succession in the past few months,” Snyder said.

How does this year compare?

The two main entities overseeing food safety in the U.S. are the Department of Agriculture, which regulates certain meat, poultry and egg products, and the Food and Drug Administration, which manages all other foods.

From October 2023 to September 2024, the FDA issued 179 recalls for food and cosmetic products under its highest classification, which it defines as the possibility of “serious adverse health consequences or death.” This is up from the 145 cases a year before, but down from the 185 recalls with the same classification during fiscal year 2022.

So far in October and November of this year, there have been 18 high-risk recalls, according to the data.

An FDA spokesperson said in a statement that the nation’s food supply “remains one of the safest in the world.”

Meanwhile, the USDA Food Safety Inspection Service has issued about half the number of product recalls so far this year compared to last year, according to a spokesperson. There have been 30 recalls this year as of Nov. 12 compared to 65 recalls last year, according to a statement.

Those recalls are mainly voluntary, unless a company refuses to recall “adulterated or misbranded product,” according to its website.

“FSIS remains committed to reviewing all its food safety policies to continue protecting public health through science-based inspection methods and policies,” the spokesperson wrote.

Preventing health risks

Byron Chaves, a professor and food safety extension specialist at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, said food safety is complicated because the food supply is complicated.

“So, when it comes to safeguarding and protecting the food supply, there’s many different facets, right?” Chaves said.

In the food safety puzzle, Chaves said everyone – the federal government, state governments, processing companies, growers, retailers and consumers – has a piece. The prime tools are inspection and enforcement from the federal government and microbial interventions and supply control on the industry side, he said.

Snyder said modern food safety programs do not rely primarily on testing because to find 100% of contaminated food, 100% of food produced would have to be sampled. Instead, the programs also include preventive measures.

Most contaminated food does not make it to the store, but it does happen, Chaves said. He said the industry practices in place typically work.

“And so because they work, and there is statistically sound and robust sampling plans that many or the majority of facilities actually apply, then they are able to catch contamination in a product or on a food contact surface before that product leaves the facility, right?” Chaves said. “If that weren’t the case, we would be seeing hundreds and hundreds of more recalls.”

Pulling products

Large-scale recalls can happen when a lot of products get contaminated in a single event, Chaves said. For instance, a contaminated ingredient ends up in multiple products, or there is a contaminated food contact surface that multiple products go through.

“At the end of the day, microbes and chemicals are just microbes and chemicals, they are not intentional about what they do, right?” Chaves said. “So that is where food regulations and food safety education, food safety awareness becomes so important.”

Recent changes have helped to make the food system safer, said Jaydee Hanson, policy director at the Center for Food Safety. For instance, the Food Modernization Act signed in 2011 gave the FDA authority to take products off the market.

“What this has done is encourage the companies to, as soon as they know that there’s a problem, to take stuff off the market,” Hanson said. “Because they don’t want to be seen as a company that the FDA shuts down because they’re selling unsafe food.”

Still, Hanson said he would like to see improvements such as more distance separating vegetable operations and meat operations. But that might be hard as water is getting more scarce and producers experience extreme weather like drought, he said.

Hanson also said faster speeds on the production line can cause problems in food safety and health of line workers.

“You know, when you have a whole half of a cow go by somebody every couple of seconds, that’s not much time to visually inspect them,” Hanson said.

When certain recalls do happen, Synder said agencies will list the time frame for when a product is produced. She said that the time frame is based on when a product is made, distributed, sold, eaten and when cases of illnesses start.

“And if it’s, for example, contaminated with a pathogen, there’s a certain amount of time until the symptoms emerge, and then the person has to seek medical treatment,” Snyder said. “The case has to be recognized, the pathogen identified, entered into the surveillance system and then FDA has to, for example, conduct its investigation.”

Even though contaminated food is not everywhere, Hanson said people should listen for warnings about the food they eat.

Hand washing, using a meat thermometer, avoiding cross contamination and returning recalled products, are steps consumers can take, Snyder said. But there are limitations, she said, and she emphasized the important role food agencies play in detecting outbreaks, conducting investigations and getting products out of the market quickly.