When International Prep Academy in Champaign sent students home in March 2020, 10-year-old Ana Hernandez and her mom started what they called the “Hernandez Homeschool.”

Ana’s mom, Genevieve Kirk, looked up different teaching resources and curriculum to keep Ana on track, she said.

This process, she said, connected her with both of her children—Ana and Ana’s 12-year-old brother Mateo — in an entirely new way.

“I actually felt more in tune with my kids’ learning during that time than I ever had before because it was right in front of me,” Kirk said.

Although Ana did relatively well with online learning, Kirk said, she had a harder time learning without face-to-face interaction.

This struggle has been true for many dual-language students since that in-person connection was lost during COVID, local language educators said.

Because of the interactive nature of language learning face-to-face, they said, is crucial.

A loss of second-language skills

Ana, a fifth-grader, moved back to in-person classes at International Prep Academy in August. She said she can tell that her Spanish got worse during online learning.

“I didn’t really speak any Spanish, and no one else really did,” she said. “When we came back in person, they were kind of forced to speak because you have to answer the questions.”

Ana hasn’t been alone in her struggles.

In the 2020-2021 school year, students in grades three through eight learned at a lower rate than the previous school year, according to research by the educational-assessment group NWEA.

In dual-language schools like International Prep Academy, teachers said that students faced the challenge of a lack of in-person practice and coaching of their target language.

These challenges have been felt both by native English speakers and children learning English as a second language, they said.

Among those struggling was Ana’s classmate, Ismael Lopez, who was born in Peru.

His native language is English, he said, but sometimes he speaks Spanish at home with his parents, whose native languages are both Spanish

But, Isamel said he’d rather speak English.

“I’m more comfortable speaking English,” he said. “It’s much simpler for me to speak because, [with] Spanish, I have to have a lot of corrections.”

Ismael said he tries to speak Spanish with his mom, who is working toward her college degree and learning English.

Even though he occasionally speaks Spanish at home, Ismael said it was still difficult to learn Spanish online because Zoom would often lag or log teachers out.

“They were telling me, ‘How did you get it wrong?’ and I say, ‘You haven’t helped me with this’ and they said, ‘Yes, I did’ and I said, ‘Well you were glitching at that time,” Ismael said.

The transition back to in-person classes wasn’t much easier, he said. He had to get used to being in a typical classroom setting again and to the new COVID-related rules, like social distancing and wearing masks.

Teachers notice the gap in learning

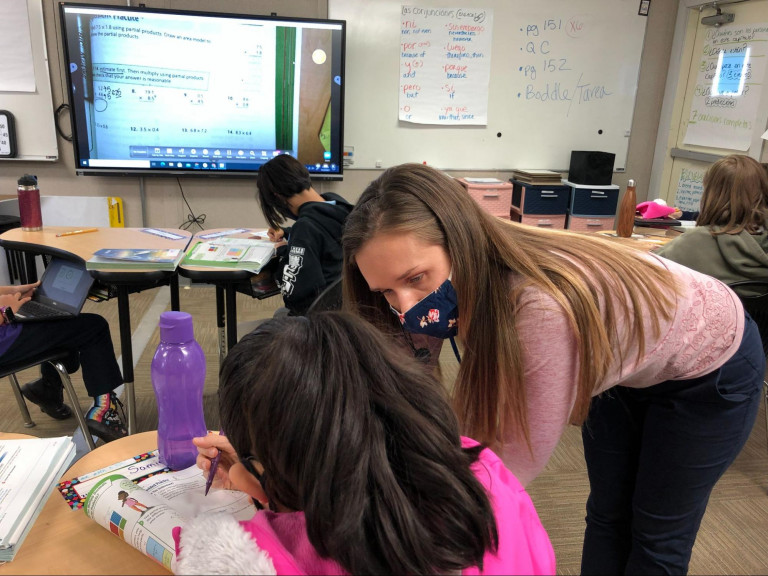

The learning gap caused by COVID-19 quickly became apparent early on this school year, said Katlyn Zabala, Ana and Ismael’s fifth-grade teacher.

“I have seen the biggest gap in their ability to produce Spanish because they weren’t in classrooms speaking with each other in Spanish or writing in Spanish,” she said.

The most frustrating part of the semester, she said, has been adjusting her lessons as she identifies gaps in her students’ knowledge and abilities.

“I don’t know what they don’t know until I come to that moment,” Zabala said. “At any given moment, there’s a gap that I did not foresee.

“So many lessons I have with one purpose, but in the middle of the lesson, I have to change the purpose because I realized there’s a gap.”

The difficulty for students learning a language virtually, Zabala said, was creating a meaningful connection with others, which she said is the whole point of learning a new language.

“Humans need humans, and without humans, there’s no relationship,” Zabala said. “The purpose of a language is to create and maintain a relationship.”

She compared learning Spanish to learning math, which, when broken down to the basics, doesn’t hold much meaning, she said.

“Without being in person, keeping up with your Spanish just becomes another task to do,” Zabala said.”There’s actually nothing magical about it just like four times four is 16.

“Well ‘hablar’ in the present tense in the ‘yo’ form is just ‘hablo.’ It’s just a task.”

Administrators at International Prep Academy know how difficult the transition back to in-person classes has been, said Jonathan Kosovski, International Prep Academy’s principal.

But students are also happy to be back in school, and teachers’ main focus right now is making up for some of the learning lost from COVID, he said.

“That’s kind of where we’re at now is trying to fill those holes and see how we can fill the holes, both based on language, and then also based on content and academic abilities, too,” Kosovski said.

The educators at International Prep Academy aren’t the only ones who’ve said they’re working to close COVID-related gaps.

Teachers at Leal Elementary School in Urbana are facing many of the same challenges, said Gabriel Nardie, a third-grade dual-language teacher at the school.

He said he knows the level of Spanish students are supposed to be at but that many of his students aren’t there.

“It’s just lower now, dramatically lower in some cases, because they’ve missed hundreds and hundreds of hours of exposure to the language,” Nardie said.

The best thing he and other teachers can do right now, he said, is meet students where they are.

Reconnecting with students

Teachers need to be patient with the students so that they, as educators, can provide education that students can grow from, Nardie said.

Often, he said, that means he has to re-teach certain lessons or things that students might have known if they were in the classroom last year.

“Every teacher is going to do their best to help these kids grow from where they are right now and build them up with praise and confidence so that they continue to grow just like you normally would,” Nardie said.

This is exactly the type of mindset that teachers should have, according to researchers.

There should be some more grace for teachers to work with students to address their needs, said Margaret Marcus, a visiting professor at the University of Maryland and a dual-language researcher.

Now, she said, we should be thinking about some of the mental health impacts of COVID on young students.

“Another part of that is this whole social-emotional part, right?” she said. “And how kids are doing being in school, whether they’ve experienced a loss from COVID or another traumatic event.”

COVID-19 has also emphasized the importance of enrolling kids in dual-language education and keeping them enrolled, said Patricia Lozano, executive director of Early Edge California, an advocacy organization.

Part of this involves urging government leaders to fund dual-language programs, she said.

“We need to really prioritize enrollment of dual-language learners,” she said. “And at the state and the federal level, keep advocating for funds for professional development, because though those adults in the classroom need the resources.”

Even though Ana and Ismael said they’re looking forward to life after COVID, they said they’re enjoying school so far and think Zabala has been doing a pretty good job teaching.

“Most of the time? Yeah, it’s pretty fun,” Ismael said.

Ana shares similar sentiments.

“She’s really fun,” Ana said about Zabala. “It’s really fun when you get called because then you can go up and if you get it wrong, she just explains it to you, and then you know how to do it.”