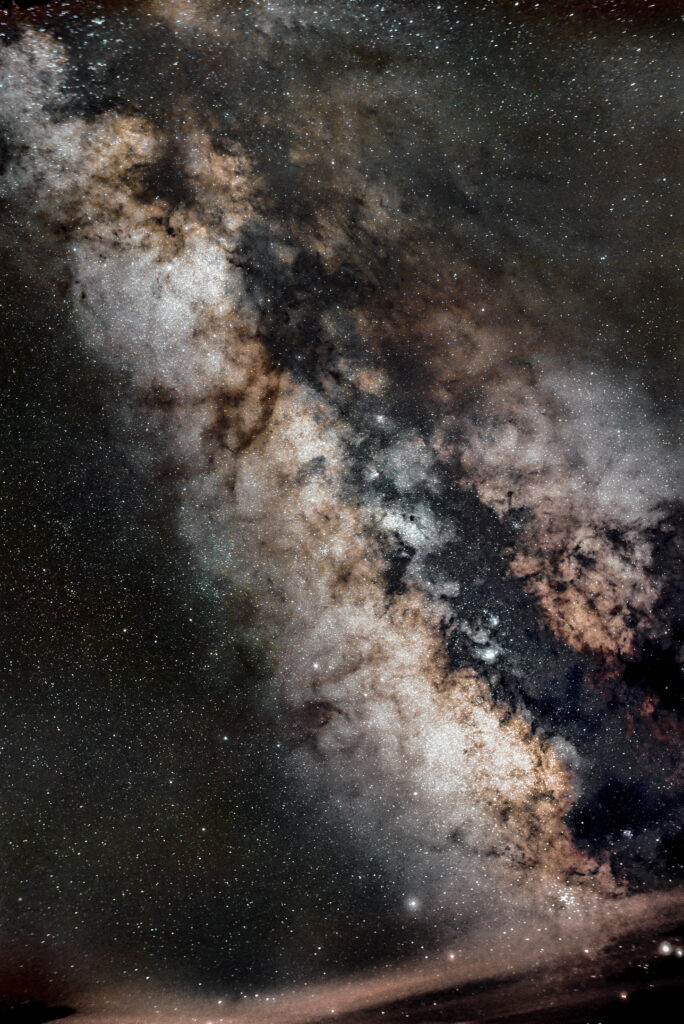

URBANA — Somewhere thousands of light years away, colorful clouds paint space with blotches and swirls of light and color. It’s a scene that would snatch the attention of any photographer, but it’s too faint to see with the naked eye.

Fortunately, there are cameras that can capture images of these faint and distant space objects. The branch of photography dedicated to capturing objects in space is known as astrophotography.

On the Discord server of the Astronomical Society at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, members share stunning images of the cosmos. One of them is U of I sophomore Pierson Lipschultz, who got into astrophotography by pure coincidence around two years ago.

“I was with my parents, and we drove into a campground where an astronomy club was setting up,” he said. “They invited us to come over the next night and actually look through everything.”

Though Lipschultz had always been interested in astronomy, he was often underwhelmed by views from telescopes because he needed to take his glasses off to look through the scope.

“I take my glasses off and I look through and I’m like, ‘Wow, that’s blurry. There’s nothing there,’” he said.

But after he noticed a group of astrophotographers, Lipschultz said he was immediately amazed.

“They were just out there looking at a tablet, seeing these pictures of nebulae just come in, and I was like, ‘I want to do that,’” he said.

The unique challenges of astrophotography

On a recent fall day, Lipschultz, seated on his couch with two laptops open in front of him, pulled up some photos of a nebula on one screen. The other laptop is connected to his telescope setup: 30 pounds of assorted gadgets and gizmos standing in the middle of the room.

“It’s an absolute Frankenstein’s monster,” Lipschultz said. “No single piece on that is from the same company.”

He said he bought the parts used, since astrophotography equipment doesn’t usually come cheap. Fortunately, he said his friends in the astrophotography community gave him good deals. He also designed and 3D-printed the mounting system.

Every piece has an important purpose, from the router to the scope, to address the unique challenges astrophotographers face compared to regular photographers.

One major difference is exposure time, or how long a camera takes in light. The duration depends on how much light the scene has. With most standard photography, exposure time is a fraction of a second, but it needs more time in darker settings to collect enough light to make the scene visible. That is why the night mode on your phone camera takes a few seconds to take a picture.

In order for a camera to collect enough light to see that dim gas and dust cloud 6,000 light years away, Lipschultz said he uses 20 hours of exposure.

“That’s 20 hours of three-minute long exposures,” he said. “And what you do is you then take all of those and you stack them.”

Stacking all of the exposures brings out the target object and drowns out the noise.

Since the Earth rotates, astrophotographers cannot just set up their scope and leave it; the whole sky would shift in their frame. To account for this, scope mounts are designed to slowly spin, counteracting this motion and keeping the target object in view, unblurred.

This movement is automated, controlled by apps on Lipschultz’s laptop and phone. Another problem solved — but there’s more.

“Over the course of the night, it’s going to get colder, and as it gets colder, your telescope is going to contract,” Lipschultz said. “So your focus point is going to move.”

The solution: a motor responsible for adjusting the focus.

Once an image is finally captured, astrophotographers move to the post-production stage, which includes decisions about color. Many astrophotographers use false color in their images, meaning the color shown in the photo is not the same as it would look to human eyes.

False color in astrophotography can represent the presence of different elements. For example, the Hubble palette uses red for sulfur, green for hydrogen and blue for oxygen. Specialized filters isolate the proper wavelengths, and the data for those three elements go into the RGB values of the image.

There are numerous palettes to choose from. Lipschultz said that’s where astrophotographers can get creative.

“You can put a scope pretty much anywhere in the world, pointing in the same spot, and it’s going to look the same,” he said. “A lot of the freedom comes out in the processing — what colors you choose to stress and stuff like that.”

With the amount of time and money he’s poured into his astrophotography setup, Lipschultz sometimes jokingly calls it his kid.

In contrast to Lipschultz’s “Frankenstein monster” setup, U of I graduate student Aniket Pant’s rig fits into a single container the size of a briefcase.

The sleek, compact device, called a Seestar, is like an all-in-one astrophotography device, known by some as a “smart telescope.”

“This is a pretty cool, nifty little kind of small-scale revolution in the astrophotography world lately,” Pant said.

It’s also cheaper compared to other astrophotography setups: hundreds of dollars, versus thousands.

Fortunately, Pant said U of I has everything students need to give astrophotography a try.

What makes central Illinois great for astrophotography

For students who are interested in astrophotography but not able to invest in the necessary equipment, the U of I library is a “very accessible” resource, Pant said.

On his blog, Pant has published photos of dazzling, star-filled skies — some of which he captured with equipment borrowed from the U of I library.

Though the cameras available through campus may not be capable of photographing dimmer, more distant objects, they can capture constellations, the Moon, the Milky Way and some brighter nebulae, as long as the light pollution is low enough.

Pant came to U of I for graduate school after completing his undergrad in Atlanta, where the stars are harder to see against the city lights.

“Coming to UIUC, it was a really different experience because you can see so much more here,” he said. “The sky is a lot darker, so your opportunity to do astrophotography here is just so great.”

It’s an opportunity both Lipschultz and Pant recommend anyone interested take. There are plenty of astronomy and astrophotography communities in east-central Illinois, beyond the U of I campus.

East-central Illinois is also home to Middle Fork River Forest Preserve, which is the first and only designated International Dark Sky Park in Illinois.

Pointing to an image of a nebula on his laptop, Lipschultz explained what makes astrophotography so awe-inspiring.

“This nebula is three-and-a-half thousand light years away, which means that the photon that came off of this nebula traveled through space for three-and-a-half thousand light years and then came through the atmosphere and then went through my scope,” he said. “It’s sort of absurd to think of how big of a journey that is to just hit an image sensor and turn into a picture.”