SPRINGFIELD – In the months after the COVID-19 pandemic forced schools in Illinois to be closed, calls to the state’s child abuse and neglect hotline dropped significantly.

The Illinois Department of Children and Family Services said in a statement June 1 that calls to report suspected abuse and neglect are down by 57% compared to the same time last year.

Child advocates believe this is not a signal that fewer children are being harmed, but instead suggests children who are at risk have become more invisible to the public and to school employees, who make the majority of calls to Illinois’ hotline.

Child protection expert Betsy Goulet says that due to the close relationships they develop with children throughout the school year, school teachers and social workers are often the most likely to identify a change in behavior signalling a child may be in danger, or learn about abuse when a child discloses.

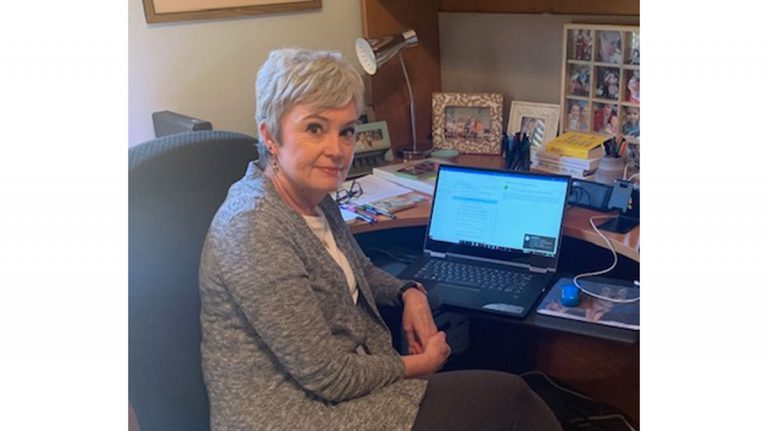

Goulet is a clinical assistant professor in the Department of Public Administration at the University of Illinois Springfield, and co-author of a recent report from the U of I Institute of Government and Public Affairs titled, “Children at Risk: Ensuring Child Safety During the Pandemic.”

She says DCFS is working on getting the message out to children that if they or someone they know is in danger, they can reach out for help directly.

The state is working with pediatricians’ offices to put information about child abuse and the help that’s available on posters hung at children’s eye level. Goulet says they’re also discussing creating a number children can text if they need help.

Goulet says she and her colleagues have been speaking with legislators about how schools need support as they prepare for a possible surge in reports that may come once they reopen.

“What are the teachers and the school social workers going to hear?” Goulet says. “How do we prepare them if over the course of these next two months, children do come back to the classroom and they have things they need to report?”

She says the state will likely need more child welfare investigators ready to respond to those reports.

“Better to think through the what-ifs right now than get caught in late August or early September with too few people to respond,” Goulet says.

She says anyone who suspects a child may be at risk should contact DCFS’ Child Abuse and Neglect Hotline at 1-800-25-ABUSE (252-2873).

Goulet spoke with Illinois Newsroom about how teachers have gotten creative about reaching out to families, and why she remains concerned by the drop in hotline calls.

This interview has been lightly edited and condensed for length and clarity.

Christine Herman: What kinds of efforts have teachers been making to stay in touch with kids who may be at risk right now?

Betsy Goulet: Teachers were making drive-bys, doing visits on porches and driveways, and that was significant. But there were students who probably weren’t coming out on the porch or the driveway. And the teachers that we’ve talked to have said that’s what unnerved them — the lack of contact (from some families).

People don’t have their support systems in place. Even if they were getting services — like mental health services, perhaps they were in some kind of support group, those kinds of things — they’re all suspended.

It’s just being really conscious of the way that this has impacted fragile families, the way that the economy has continued to create hardships, and with those hardships, sometimes that’s the environment where we see maltreatment, we see depression, and we see some families who withdraw further and further. It becomes harder for them to deal with these changes.

CH: How do you know when it’s abuse and neglect versus simply a lack of access to food or a need for other supports or services? When does it warrant a call to the hotline?

BG: That is the question that we’re constantly training mandated reporters to know; that it’s not for them to do an investigation, it’s for them to report a suspicion and to allow DCFS and the trained investigators to sort through all of the information, all the facts that would then point them to that decision that something is happening.

It’s not always clear cut. And we also know that children don’t necessarily disclose in big chunks of information, and sometimes it is something that’s a hint of a larger problem. All we ask of our mandated reporters is to make a report if they have a suspicion that a child might be even at risk of harm.

And as you pointed out, you know, is the food issue an insecurity with food? Is it something that’s happening because of neglect, or because of a lack of funds in the home? We don’t consider poverty to be abuse or neglect. It’s a condition that can create harm for kids, but it’s also a condition that we can correct with services.

CH: What about for people who don’t trust the system, for whatever reason?

BG: Absolutely. There are all kinds of perceptions about DCFS — I call them urban legends — that even exist within other systems, about DCFS. Law enforcement perceptions, or the school or the medical community. I’ve heard them all. I was a DCFS investigator, and so a lot of what I talk about, and my perception of the importance and the value of mandated reporting, comes from having done that job, and knowing how critically important it is.

We have to support those people. We have to give them the training to understand how to do the job well.

But they can only do their jobs if, as a community, we understand that children are harmed. There are people who do things to kids that need to be reported. And right now, we’re all feeling a little overwhelmed by what’s happening, and the fear that there is more of this going on and fewer people in the know.

The state’s Child Abuse and Neglect Hotline at 1-800-25-ABUSE (252-2873).

Christine Herman is a reporter for Illinois Newsroom. Follow her on Twitter: @CTHerman