DEKALB — Joseph Rupnick’s mother was a toddler when federal agents took her away from her parents and sent her to a Catholic boarding school out of state.

After that, she never spoke her first language again.

“She didn’t speak much about it. Most of what we were told was that the nuns weren’t very nice to those that spoke Indian,” Rupnick said.

President Joe Biden publicly apologized Friday for the federal policy that forcibly separated Native American children from their parents between 1819 and 1969. The U.S. government sent them to boarding schools, where they endured abuse and some even died.

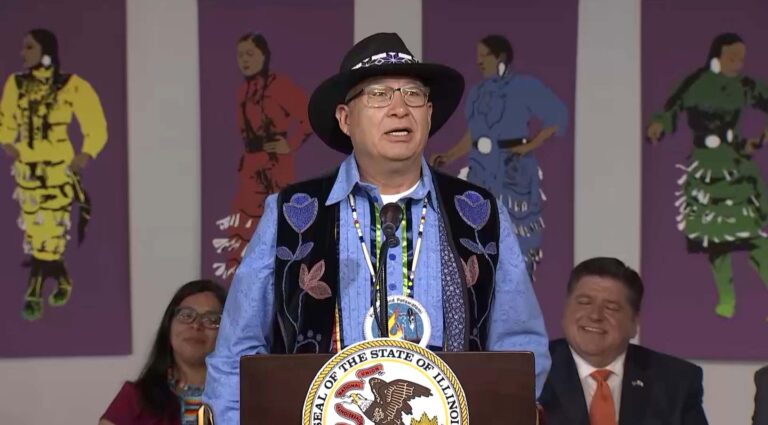

Rupnick is chairperson of Illinois’ only federally recognized tribe, the Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation.

He told IPM’s Emily Hays that after generations of children were sent to boarding schools, only five of the 4,500 members of the band speak Potawatomi as their first language.

HAYS: What has been the experience of people in your nation with boarding schools?

RUPNICK: I’ll start off with my mom, who was three years old when she was first taken to attend boarding school and they shipped her to Marty, South Dakota. So when the agents came down, my grandparents tried to say she’s not old enough. They said, “No, she’s plenty old,” and they took her to South Dakota. Of course, our reservation is in Kansas.

HAYS: Can you tell more about how the boarding schools affected your mom?

RUPNICK: She never talked Indian again. I remember when I was a little kid, my grandparents were talking Indian to us, and then she got mad at them. Part of that was because, she said, “I don’t want these kids to grow up with broken English and having somebody abuse them like I was.” That was a piece of us that was taken away, that we’ll never be able to get back.

HAYS: What do you think would be a true apology, then, for the U.S. government doing the boarding schools?

RUPNICK: While apologies are good, that does not really translate into action, and right now, tribes have to compete against each other for grant dollars for language revitalization. If the government truly wanted to make that first step, then the ultimate goal should be that no tribe should ever have to pay for language revitalization. That should be an amount that Congress sets aside that is directly paid to the tribe for those language programs.

HAYS: So do you have any language revitalization programs right now?

RUPNICK: Yes, we do.

HAYS: What does that look like?

RUPNICK: They’re doing a really good job. They’re starting to teach a lot of the youth. They also partner with our local school district, where they’re able to go in and teach the language in school. It’s open to anybody.

On top of that, we’re working towards making our language instructors certified so that those kids that do participate in that language program in school can use that as credits for secondary education.

HAYS: What would you say is your next step in language revitalization?

RUPNICK: Same as it has been since I’ve been in office. Of course, we fund our language program, try to get as many folks involved in it as we can. As a government, we’re making sure that it’s there, it’s available, and that they have the necessary funds to continue the program.

Emily Hays is a reporter for Illinois Public Media.