Leak in monitoring well being addressed by company, regulators

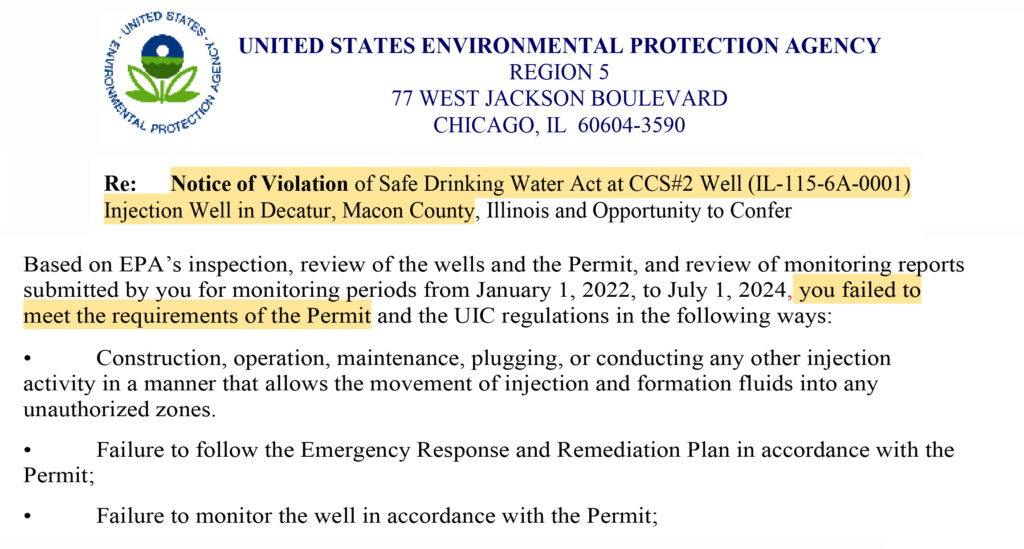

DECATUR – Agribusiness giant ADM violated federal regulations, a federal permit and the Safe Drinking Water Act earlier this year when a monitoring well at their carbon sequestration site in Decatur leaked liquified carbon dioxide into “unauthorized zones,” according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

In an August notice, the federal regulatory agency also alleged the company failed to follow proper emergency response and remediation plans after it identified the leak.

ADM’s carbon injection facility is the first and only project of its kind in the country. It stores more than 4.5 million tons of carbon dioxide generated from industrial processes at a company facility in Decatur more than a mile underground. The project began operation in 2011.

The leak was first detected in March, according to an Aug. 22 letter to the EPA from the company, although the company had known about corrosion in tubing at the well since October 2023.

In the original notice of violation, EPA’s director of enforcement and compliance for the region, Michael Harris, told ADM that the issue could be grounds for an “enforcement action, including administrative and civil judicial penalties” and that ADM’s permit for the project could be terminated.

ADM spokesperson Jackie Anderson said the company is now working with the EPA to address the issue.

“That monitoring well was plugged, is not in use, and none of the other wells were impacted,” the company said in a Friday statement. “At no time was there any impact to the surface or groundwater sources or any threat to public health.”

Roughly 8,000 metric tons of liquid carbon dioxide and other ground fluid was leaked. This is equivalent to about three days’ worth of injection, according to Anderson.

The leaked carbon dioxide stayed about 5,000 feet below ground, well below groundwater in the area, which is about 200 feet beneath the surface, according to a company document.

The Illinois Clean Jobs Coalition, a group of labor organizations and environmental advocates, were quick to criticize the company on Friday for failing to notify the public of the problem.

“There are significant risks at every step of the CCS (carbon capture and sequestration) process, and it’s not a matter of if carbon sequestration facilities leak, but rather when,” the coalition said in a statement. “Neither ADM nor the USEPA have released any details about the nature of the leak or its impacts on the local community, groundwater, or the environment, and we are anxious to learn more.”

The coalition also characterized the lack of public disclosure as “unacceptable and dangerous.”

Anderson noted that the company reported the situation to the EPA “in accordance with our permit requirements when there is no potential endangerment to an underground source of drinking water, which was the situation here.”

Other critics of the technology said the risks of carbon capture outweigh the potential benefits.

“This leak is a wake-up call. It’s a stark reminder that carbon capture is not the climate solution it’s sold as, but a dangerous gamble with our drinking water,” Pam Richart, co-director of Eco-Justice Collaborative, said in a statement.

Earlier this week, Rep. Carol Ammons, D-Urbana, filed a bill that would prevent other carbon sequestration projects from being built in areas where the sole source of drinking water is an underground aquifer.

This legislation follows a law passed earlier this year that lays out a state-level regulatory framework for CCS projects. Despite being praised by its proponents as a nation-leading piece of legislation, the law passed earlier this year does not contain any specific protections for large sources of drinking water.

ADM’s project is not subject to the new requirements outlined in that bill, and the company supported it when it was being considered by the General Assembly.

This was the subject of heated legislative debate as several lawmakers called for more protections for the Mahomet Aquifer, which serves areas around Rantoul, Champaign, Clinton, rural Tazewell County, Mason County and more.

“The Mahomet Aquifer, which sustains nearly a million people in Central Illinois, cannot afford to be put at risk by experimental technologies like carbon capture and storage,” Richart, who supports Ammons’ legislation, said.

That legislation, House Bill 5874, could be considered when lawmakers return to Springfield this November for their fall veto session.