CHAMPAIGN — Stephanie Zarate is both transgender and formerly incarcerated. Zarate says being transgender makes it difficult to find resources after incarceration — especially housing.

“Unlike cisgender, straight people, it’s difficult for us because we don’t have the support that they have,” she said.

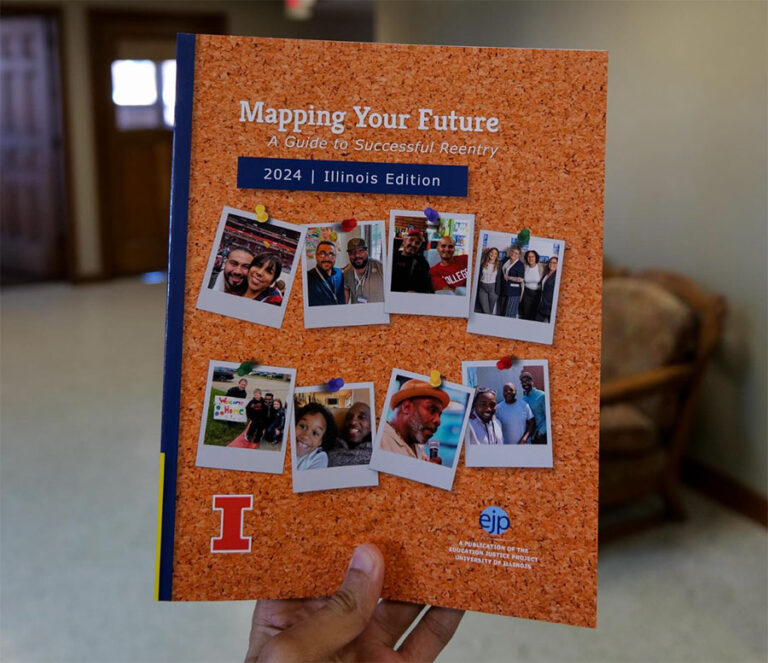

That’s why the latest re-entry guide from the Education Justice Project includes information on how to get involved in community organizations after incarceration and other resources for LGBTQ+ people.

Lee Ragsdale, the director of the re-entry guide, said EJP received input from Pushing Envelopes, a Chicago re-entry group for LGBTQ+ people returning from incarceration.

“They said, you know what, why don’t you have a chapter on this?” Ragsdale said. “And we said, that’s a great question. You know, that’s, frankly, been an oversight.”

The new LGBTQ+ chapter includes resources for housing, employment, healthcare and substance use — tailored to transgender, gender-nonconforming and queer people.

Lesbian, gay and bisexual people are incarcerated at a rate three times higher than the general population, according to the Prison Policy Initiative.

It’s often harder for transgender people to find housing because halfway houses are usually sorted by gender and LGBTQ+ people often can’t rely on family or religious charities because of their identities, Zarate said.

Zarate added that even when resources are specifically made for LGBTQ+ people, restrictions often exist that limit access for certain individuals, like those with a criminal record or who are HIV-positive.

Lydia Vision, a transgender woman, fought for years to receive gender-affirming care and hormone therapy while incarcerated in Illinois Department of Corrections facilities.

When Vision got out, Pushing Envelopes made sure she could continue her treatment — which is a challenge for many transgender people coming out of incarceration.

“Within three days, they helped me with getting medical insurance and making sure I was covered because I’m on hormone replacement therapy,” Vision said. “They don’t sell it over the counter. So I had to get it together.”

Connecting formerly incarcerated people to resources like housing is especially important, Vision said, because, without it, getting parole and leaving prison isn’t an option.

“If you don’t have a place to go from prison, you don’t get to leave,” Vision said. “They will hold you until your parole time’s up. So essentially, due to lack of a house and place to go, I may have had to stay in prison for almost three more years.”

The new re-entry guide is currently being distributed through prisons throughout the state.

Ragsdale said each year the guides get more inclusive and accessible to more formerly incarcerated people throughout Illinois.

“One of our alumni said, ‘This guide was our internet,’” Ragsdale said. “That just shows you how comprehensive, useful, and we hope, empowering, the guide is, that somebody can come to it and get information on any re-entry-related topics.”

Farrah Anderson is a journalist and student at the University of Illinois. Follow her on Twitter @farrahsoa.