The Illinois Department of Corrections has revised its publication review policy to include a centralized appeal process for incarcerated people who feel they’ve been unfairly denied access to certain reading materials.

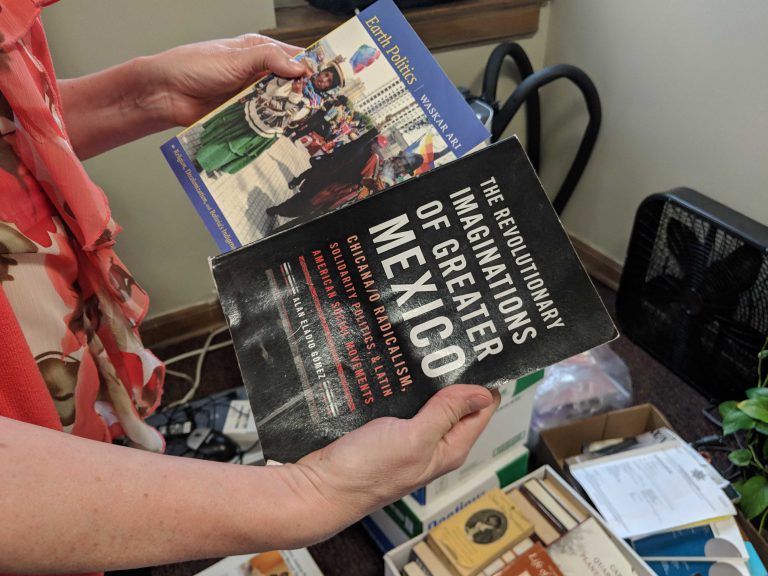

The policy change comes after Illinois Newsroom reported the removal of more than 200 books, most about race, from a college-in-prison program’s library inside the Danville Correctional Center earlier this year. State lawmakers held a legislative hearing in July to discuss the issue. During that hearing, the new director of IDOC, Rob Jeffreys, promised to overhaul the department’s existing publication review policy.

The revisions include a more detailed description of the types of content that should be barred from entering a prison. The revised policy, which is dated Nov. 1, also notes that content which “blatantly” encourages violence, hatred or group disruption, or “overtly” advocates for such, may be barred from prisons. The previous iteration of the policy did not include the words “blatantly” and “overtly.” The new policy also expressly prohibits materials that describe how to use or make weapons and drugs, as well as anything that might help a prisoner escape, including detailed maps of the areas that surround Illinois state prisons.

The revision explicitly breaks down who within the prison is responsible for reviewing materials sent to inmates, as well as religious texts and publications used in educational programming. Additionally, the new policy requires the establishment of a centralized publication review committee — made up of at least four individuals within the correctional system — which has the final say on whether a publication should or should not be allowed inside.

Ban on photocopies and downloaded material

The policy also includes a new exclusion: photocopied and downloaded material. The policy states that “photocopies or material downloaded and printed from a computer, are prohibited and shall not be accepted for assessment or review.”

The policy provides an exception for legal documents, “newspaper clippings” and materials for educational programs. Lindsey Hess, a spokesperson for IDOC, said articles from digital-only media outlets would fall under the category of “newspaper clippings,” and therefore be allowed inside state prisons.

[perfectpullquote align=”left” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]”This is going exactly in a backwards direction.”-Rebecca Ginsburg, director of the Education Justice Project[/perfectpullquote] Rebecca Ginsburg, director of the Education Justice Project, the college-in-prison program that was subject to a mass book removal conducted by Danville prison staff earlier this year, said the new ban on photocopied materials poses a problem for incarcerated people.

“We’re relieved it doesn’t apply to us, but concerned it applies to everybody else,” she said. “People get articles sent in from family members and loved ones all the time that are photocopied.”

Ginsburg said photocopies are one of the primary vehicles for distributing knowledge in a prison setting. She said she knows incarcerated people who have had family members send them photocopies of books because it’s cheaper.

“This is a new thing… this is going exactly in a backwards direction,” Ginsburg said.

Hess did not respond to a question asking why the department instituted a ban on photocopied and downloaded material.

Alan Mills, an attorney with the Chicago firm, Uptown People’s Law Center, said the ban on such material is “absurd.” Mills sued the department on behalf of multiple publishers and one author who allege that IDOC violated their constitutional rights by improperly censoring material they sent to incarcerated people. He said several lawsuits are ongoing while two are in settlement discussions.

While the new policy requires that prison staff notify the intended recipient of the reading material as well as the publisher — if it was sent directly from the publisher — Mills said they should also be required to notify every sender, as well as the author.

He said he hears frequently from parents of prisoners who try to send their loved ones reading material that is ultimately rejected.

[perfectpullquote align=”right” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]”Somebody spends a lot of money buying a book, sending it in, and then they just get it back with no notice as to what they did wrong.” –Alan Mills, attorney with Uptown People’s Law Center[/perfectpullquote]“That’s why I’m particularly concerned about the sender getting notified. Because there’s no way the parent knows why it got rejected. That’s very confusing. Somebody spends a lot of money buying a book, sending it in, and then they just get it back with no notice as to what they did wrong.”

Mills said he’d like to see the policy changed to require notification all of senders, as well as authors of any material that’s censored by prison staff.

Appeals process

The policy lays out an appeals process for prisoners who receive publications through the mail, but Ginsburg said it’s unclear whether that process applies to educational programs like EJP.

“I feel that this (policy) does not protect programs like EJP. I don’t feel that this puts in place anything to prevent other programs and other facilities from having books removed,” she said.

Hess, the spokesperson for IDOC, said staff at prisons will no longer have the authority to censor books brought in by educational programs. If a prison’s educational facility administrator or publication review officers believes something brought in by the program is questionable, Hess said IDOC’s central publication review committee would step in to make a final determination.

Both Ginsburg and Mills worry the new policy is still too broad in its definitions of material that may pose a threat inside. Ginsburg points to the phrase in the policy that states that a publication may be disapproved if it is “detrimental to the security or good order of the facility.”

“So at any point somebody… can say, we don’t want this kind of talk in here or this is going to stir up things,” she said. “I believe it gives them an out.”

Mills said the phrase “it encourages or instructs in the commission of criminal activity” could be interpreted to bar inmates from receiving historical publications, particularly those that cover the civil rights era.

Ginsburg said IDOC staff have expressed a willingness to consider feedback on the policy.

“I don’t feel as though this is over at all,” Ginsburg said. “I was really encouraged to learn that the department is going to continue to accept suggestions about how to improve this directive, and make it more responsive to the needs of universities, like the University of Illinois program, the Education Justice Project, and the educational needs of people who are in prison.”

Follow Lee Gaines on Twitter: @LeeVGaines