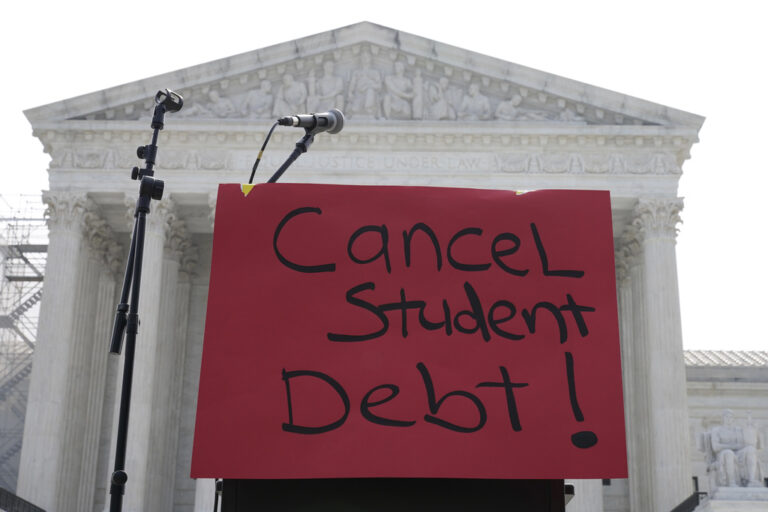

URBANA — Americans owe more than a trillion dollars in student debt. But those hoping for relief from President Biden’s student loan forgiveness plan are out of luck after the plan was struck down by the Supreme Court.

According to the Institute of Education Sciences, the average cost of college has nearly doubled in the last 30 years, going from about $15,000 a year to $29,000. Students are having to take out more loans to keep up.

Because student debt is one of the few kinds of debt that won’t be discharged in bankruptcy proceedings, it’s causing many to take it into consideration when choosing their careers, said Jennifer Delaney, an associate professor in education policy at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

According to Delaney, fields like education and public defense are getting hit hard as more students choose to pursue more lucrative career fields like tech and medicine, even if they might have a passion for something else.

“If it gets too hard and if student debt itself is playing a role in individuals, say, not becoming teachers, long term, we’re losing talent,” Delaney said.

Molly McLay, a licensed clinical social worker who lives in Urbana, finished her masters degree in social work in 2011. She worked in public service as a social worker for more than 7 years, paying down her student debts with the hope of having the remainder forgiven under the Public Service Loan Forgiveness program (PSLF).

The program isn’t enough to make up for the lack of compensation in these very valuable fields, she said.

“It’s really disheartening to know that those of us who have chosen to go into fields where we can help people and make the world a better place, because we happen to be in fields that don’t pay as well, that we are going to have this debt that we’re just going to be trying to pay off but barely making a dent in it, because of the interest rates,” McLay said.

McLay had started getting her doctorate with hopes of becoming a professor of social work but had to take a medical leave after being diagnosed with a connective tissue disorder. She said this made her question whether she would ever be able to work full-time again. And full-time employment is a requirement to qualify for the PSLF. So after she heard about the the Biden administration’s student loan forgiveness plan last August, she said she felt like she finally had some hope.

“When this plan was announced, I felt like there was a lifeline,” McLay said.

Now, with debt forgiveness off the table in the short-term and because she doesn’t qualify for deferment while on her medical leave, McLay said she’s having to consider trying to return to work full-time, even though she feels physically unable to work the hours she used to.

Under the Biden Administration’s plan, borrowers who had received federal loans could have had up to $10,000 of debt forgiven, and borrowers who had also received Pell Grants to attend school could have had up to $20,000 forgiven.

The Biden administration says it’s started the process to open up a different path for forgiving debt. But according to Prof. Delaney, this pathway is likely to take much longer than the previous plan.

The first plan involved the 2003 Higher Education Relief Opportunities For Students (HEROES) Act, which gives the Secretary of Education the power to offer relief and grant waivers “in connection with a war or other military operation or national emergency” to people who have received student financial aid. Though the Biden Administration argued that this statute gave them the authority to forgive some student loans, given the COVID-19 pandemic, the Supreme Court disagreed, declaring that the Administration had overstepped its authority.

After the Court’s ruling, the White House released a statement in which they promised to pursue loan forgiveness through the Higher Education Act, which would require them to go through a process called “negotiated rulemaking” and would likely not take effect until sometime in the fall, Delaney said.

Some borrowers say they’re not holding their breath while they wait.

Bryan Goode, who lives in Urbana and works as a technical recruiter, graduated college in 2013. Now, 10 years later, he said he’s only just starting to be able to tackle his loans.

While he said any amount of loan forgiveness would be great, Goode isn’t very confident it will happen.

“It’s difficult to get excited,” he said. “I think that it’s very tenuous and sort of difficult to keep that optimism up — that something like that is coming around the corner.”

After years of pandemic-era pauses to payments, the White House statement also said the Administration is instituting a year-long grace period for missed payments, extending from this October until the end of September 2024.

The Administration also announced an update to an existing income-driven repayment plan, called the Saving on a Valuable Education (SAVE) plan. Under the revisions, borrowers who sign up would have payments cut from 10% of their income to five percent, see the amount of income considered to be non-discretionary — and therefore protected when calculating loan payments — raised to the annual equivalent of a $15 minimum wage, and have loan balances forgiven after 10 years of payments instead of 20 years for borrowers with original loan balances of $12,000 or less. Borrowers can learn more and sign up on the Federal Student Aid office’s website.

Though all borrowers are eligible for this plan, for Delaney, this revamp is just a start.

“Revising this program is great,” she said. “But people need to know about it, and they need to opt in.”

The re-entry is going to be tough for many borrowers who have gotten out of the habit of making monthly payments for the last three years, Delaney said.

She advised borrowers to make sure they have their account information, check who their loan servicer is and start budgeting for payments now, while the payment pauses are still in effect.

“Ultimately, they are going to restart, and it’s probably going to be messy.”