You may know White because his name is on your driver’s license or you’ve seen his tumblers at parades. But there’s a lot more to White’s legendary political career as it comes to an end.

CHICAGO — Democrat Jesse White is leaving office next month as Illinois’ longest-serving and first African American secretary of state.

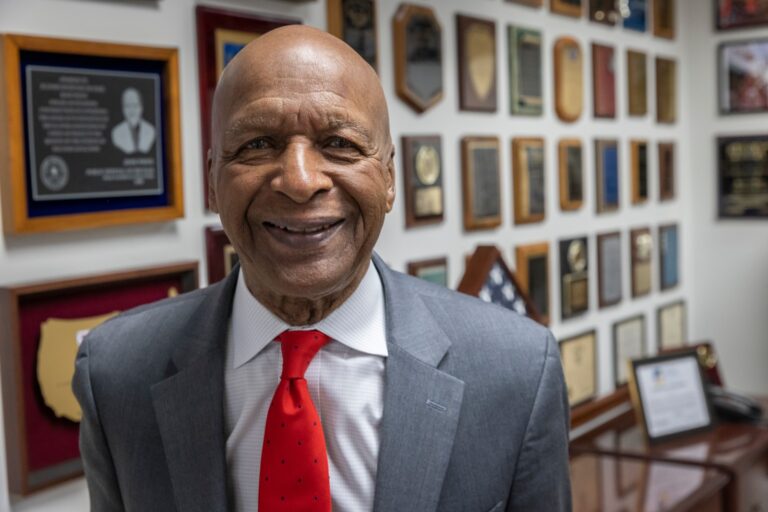

His office filled with a lifetime of trinkets and mementos, White is one of the few remaining holdouts at the James R. Thompson Center as the building’s makeover into a downtown tech hub for Google intensifies.

Listen to this story here.

Just as state government’s longtime Loop headquarters is a relic from another political era, so too is White, who first came to Springfield when Gerald Ford was president and, at 88, looks and acts as hale as he did during his first statewide run in 1998.

He may be soon ending his political career, but the fire that propelled him into power is still as intense as ever.

“When it comes to Jesse White, when you say I cannot achieve, my response is, ‘Watch me,’ ” he said during an interview in his Chicago office.

A portrait of his political mentor, former Cook County Board President George Dunne, hangs over the table where he is seated. Dunne, a onetime North Side political powerhouse, first got White involved in politics.

As a statewide office holder and former Illinois lawmaker, White has long outlived Dunne and served under every Illinois governor between Democrats Dan Walker in the mid-1970s and JB Pritzker today. White has been in state or county office ever since Chicago’s mayor was Richard J. Daley.

White’s name is on every driver’s license. But politically, that name has held a golden patina during his six statewide elections as secretary of state.

White’s legacy extends well beyond his government and political exploits. He’s in his 63rd year heading the tumbling team that bears his name, and he came within an eyelash of being a Chicago Cub.

His life has been shaped immeasurably by his race and by the racism of others.

The racism that followed White throughout his life

As a college student at Alabama State in the 1950s, White was a witness to one of the watershed moments in America’s civil rights movement.

He attended Martin Luther King Jr’s church in Montgomery, Ala., and got to know King before he became a nationally known civil rights leader. King was a regular at White’s college basketball games and slipped him money after each contest because he knew White came from a poor Chicago family.

At church one day, King announced plans to desegregate Montgomery’s bus system through a nonviolent boycott, a concept that seemed foreign to a headstrong and youthful White.

“I raised my hand. He said, ‘Jesse White, what can I do for you?’ I said, ‘Dr. King, you know me and you know me well, and you know I’m from Chicago and we don’t operate like that,’ ” White recalled. “He said, ‘If you just follow the script, you’ll find out we’ll do quite well.’ ”

After a year of protests, King’s movement prevailed in Montgomery with White ‘following the script’ and playing a small, supporting role.

But despite the blow to racism King, Rosa Parks and so many others delivered in Alabama, racism persisted, and it followed White as he moved around 1950s and 1960s America.

White used his athleticism to become a semi-professional baseball player who played seven years in the minor leagues, including within the Chicago Cubs’ farm system.

White was heckled by fans for the color of his skin in Texas. And in Minnesota, he got in a fistfight while defending himself against a white man unhappy he was eating with other teammates in a restaurant.

In 1963, White was playing for the Cubs’ AAA affiliate in Salt Lake City. He put up respectable numbers that year: a .285 batting average, 35 stolen bases, seven triples.

After White had hit his first and only home run that season, a female reporter with the local newspaper asked to have lunch with him to talk about his budding professional career and the work he was doing in Chicago’s inner city, White recalled. He’d formed his tumbling team four years earlier.

White accepted the invitation, the two grabbed a booth at a local diner, and in walked an influential coach for the Cubs organization, who spotted the two together and later confronted White when the meal was over, he recalled.

“He said, ‘You were having lunch with a white woman,’ ” White remembered. “I said, ‘That was a reporter.

‘No, don’t BS me. No, that was your girlfriend,’ ” he recalled the coach telling him.

Then, the hammer dropped. The coach told White he had been on a shortlist to be called up to the Cubs. But after seeing the two together, that wasn’t going to happen.

It was a decision White said dripped of bigotry.

“As it turned out, I never had a chance to make the majors,” White said, with a hint of regret in his voice as he retells the story six decades later.

White played third base and the outfield, had a career minor-league batting average just under .300 and had a knack for stealing bases. Had he made it to Wrigley Field, he might have been the one to fill the glaring weakness on the Cubs team that agonizingly lost the pennant to the 1969 Miracle Mets: centerfield.

Tom Ricketts, the current Cubs owner, told WBEZ he’d never heard that “poignant story of racism” from White.

“It makes me admire him even more,” Ricketts said. “It saddens me that the Cubs, the team Jesse and I love, were involved in this incident. Though it happened decades ago, it clearly must feel like yesterday to him.”

Last year, the team honored White with a one-day major league contract.

“As far as the Cubs are concerned, he retires as a Cub for life,” Ricketts said.

“I don’t dislike anyone because of how they came to this world”

Fast forward to White’s time as secretary of state, White and his tumbling team were pelted by debris from racist revelers at the South Side Irish Parade, prompting him never to partake in the St. Patrick’s Day event again.

And in 2018, during the midst of a heated gubernatorial campaign, secret government recordings of former Gov. Rod Blagojevich and Pritzker surfaced from 2008. The two were discussing names of potential African Americans whom Blagojevich could appoint to fill the U.S. Senate vacancy being left by Barack Obama when he won the presidency.

In the call, Pritzker described White as “the least offensive” choice among other potential African American nominees, igniting a racial firestorm four years ago. But Pritzker and White, together, snuffed out the controversy.

“That fell on deaf ears because I know where his heart is,” White said of Pritzker. “I know what a fine gentleman he is. I know about his family.”

For his part, Pritzker today said White deserves honor and represents “a tremendous example for all of us in public service.”

And yet, despite all of the racial indignities White has endured through his life, he said he never has felt anger or distrust for white people.

“I don’t dislike anyone because of how they came to this world,” White said.

It’s a philosophy that helped make him one of Illinois’ most popular and enduring political figures.

White’s enduring popularity at the polls

Four times, he was the leading vote-getter on the ballot as a statewide candidate. Once, he won all 102 of Illinois’ counties, even some downstate where it’s not unusual to spot someone flying a Confederate flag. That clean sweep is something no governor has done in at least 100 years. Nor did Obama do it during his runs for the Senate and presidency.

Democratic Sen. Dick Durbin shared the statewide ballot twice with White and both times had fewer votes. The state’s senior senator calls White a “legend in Illinois politics” and honored him in a floor speech in the U.S. Senate earlier this month.

“To carry all 102 counties is a political feat,” Durbin told WBEZ. “It says something about who he is and what he represents. The ‘who’ part of it is an amazing life story….He certainly came up the hard way in a tough period of American history, became a public figure and used his public stardom and his own determination to help so many people.

“You have to wonder in this time of political division how one man can be so universally loved and respected as Jesse White is,” Durbin said.

But in 1998, the year he first ran for secretary of state, White didn’t initially get that “love and respect” he now has.

In fact, White says then-powerful House Speaker Michael Madigan double-crossed him.

White, then Cook County’s recorder of deeds, sought an audience with Madigan to seek his support for a secretary of state bid. But Whites says the ex-speaker told him he wanted a downstate Democrat to be secretary of state — not someone from Cook County — in order to enhance geographic balance on that year’s Democratic ticket.

White left the meeting only to learn later that Madigan, in fact, was helping then-Orland Park Police Chief Tim McCarthy mount a bid for secretary of state. McCarthy, a former U.S. Secret Service agent, was regarded as a national hero more than a decade earlier for taking a bullet intended for former President Ronald Reagan in 1981.

White recalls later confronting Madigan.

“I said, ‘Speaker, when I spoke with you a few months ago, I indicated I had a desire to run for secretary of state, and you said that you weren’t going to support anyone from Cook County.’ I said, ‘Tim McCarthy’s from Cook County, plus he’s a Republican.’ [Madigan] says, ‘Let me say this to you: ‘I believe Tim McCarthy will bring more to the party than you.’ ”

White proved Madigan, who could not be reached for comment on this incident, wrong. White wound up thrashing McCarthy in the primary and moved on to defeat Republican Al Salvi that fall by a similar spread.

Salvi remembers how difficult it was to attack White because of his charitable work with his tumbling team.

White also refrained from attacking GOP gubernatorial nominee George Ryan for a corruption scandal inside Ryan’s secretary of state’s office that ultimately exploded and sent Ryan to federal prison after his governorship.

But Salvi did attack Ryan in the campaign. And it helped White as mainstream Republicans aligned with Ryan bailed on Salvi.

Today, Salvi considers White a friend and says he’s been a good secretary of state.

“He is a superstar. There’s just something about him. He’s very likable. Usually, political opponents…end up hating each other, frankly, in almost every case. He and I were friends at the end of the day after the election was over,” Salvi said.

“I just wish there were more Jesse Whites, in a way, in both parties. Everything is getting so divisive, and not just in Illinois, but nationally. I think Jesse White is sort of a model of what both parties should aspire to,” he said.

White’s legacy lives on in driving policies and influencing Chicago’s youth

As secretary of state, White helped tighten seat-belt and anti-drunk-driving laws, secured more stringent licensing requirements for teen drivers and promoted organ donations. Using a cell phone and texting while driving is illegal now because of him.

As significantly, after inheriting an office Ryan had led corruptly, White served without scandal. Arguably, that’s an accomplishment in itself given the state’s infamous history, as Ryan’s example demonstrates, as a breeding ground for corrupt public officeholders who wind up in federal prison.

But White’s reach has extended beyond all of that.

More than 18,000 kids came up through his Jesse White Tumbling Team during the past 63 years, sometimes coming from impoverished or single-parent homes.

Angela Spears is one of them.

She was raised by her mom in the southwest suburbs and joined the tumblers in the early 2000s. She’s now a lawyer and views White as a father figure whose mantra —–- “doing something good for someone everyday” — shaped her life.

“As an attorney, it is something I really have instilled in my own practice, and it’s how I live my life,” Spears said.

White said he still intends to remain active in public life and with his tumbling team.

But after all he’s accomplished and endured, he said he wants to be remembered as someone who helped people, believed in ethical and efficient government and lived up to his word.

“I was determined to always obey the rules of good government. It’s also based on how I run my life,” he said. “I was raised to be honest, to be fair, and to not only take on a job but the responsibility that goes with it — and that always my word be paramount.”