Legal battles have waged for years to force drug companies to pay for their role in America’s opioid epidemic. Finally, in landmark settlements over the last year, thousands of states, counties and local governments have won more than $50 billion from opioid makers, prescription drug distributors and pharmacies.

But now these 3,000 state and local governments face another daunting task: how to figure out the best way to use those dollars to blunt an epidemic of drug addiction that has killed more than half a million people.

Listen to this story here.

States are just starting to receive the funds and begin the process of answering that question.

Some of those states have turned to Sara Whaley for help. Whaley is an opioid policy researcher at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. Her big concern is that local officials won’t invest the money in methods, like harm reduction or treatment, that have proved to save lives.

“It’s not as easy as just putting the money towards evidence-based programs,” she said. “There’s this unfortunate layer to it that some of this stuff is political and personal.”

In other words, all that money is forcing officials to reckon with long-held beliefs and judgements about addiction. Is addiction a crime or is addiction an illness? Will officials look to build jails and hire more police, or will they look to treatment models and care?

Some lawmakers push funds toward treatment, not punishment

Some states, including Rhode Island and Minnesota, have set up statewide councils of elected officials and experts who are holding public meetings to decide where some dollars should go. A chunk of the settlement money in each of those states is also going to local governments and Native American tribes.

Minnesota established its Opioid Epidemic Response Advisory Council in 2019 to distribute about $15 million in state fees imposed on opioid manufacturers and distributors. Council members will also distribute a portion of the forthcoming settlement monies.

Dave Baker is chair of the council and a state representative. Baker’s view on addiction shifted after his 25-year-old son Dan died of an overdose in 2011. Dan had struggled with addiction after getting prescribed opioids for a back injury.

“He was a great kid. He was a good student. He was a good athlete,” Baker said. “When this pill hit him, it changed everything in his brain.”

Shortly after Dan’s death, Baker came to better understand addiction, and the scientific information he learned as part of the opioid response council helped him recognize how to best help people like his son.

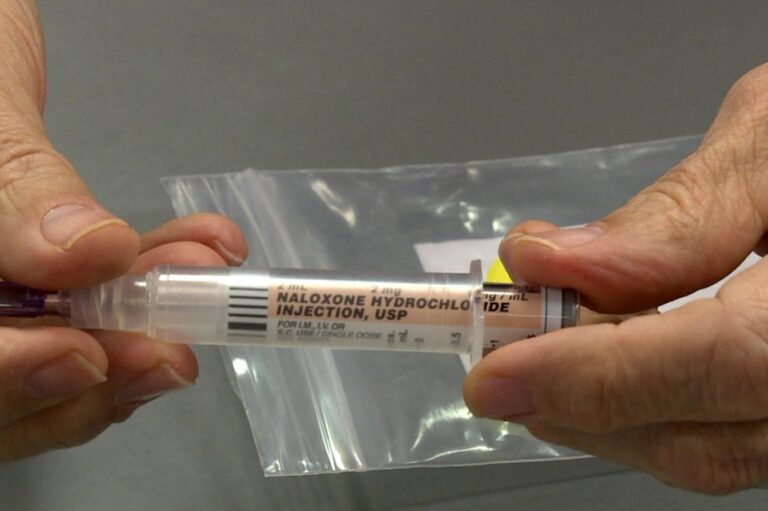

He learned from harm reduction experts that distribution of naloxone, a drug that can reverse opioid overdoses, is an important investment.

Over the three years the council has been running, it’s awarded more than half of its $5.7 million in grants to groups that distribute or train people how to use naloxone, how to distribute clean needles or offer medication-assisted treatment.

Three quarters of the $300 million in Minnesota’s opioid settlement funds will go to counties and local governments. Baker worries some might blow the dollars on jails or other law enforcement efforts because they think about addiction the way he used to think about addiction.

Settlement spending has some restrictions

The opioid settlement money does come with some spending guardrails. For example, the biggest opioid settlement is between 46 states and Johnson & Johnson, and three prescription drug distributors – AmerisourceBergen, Cardinal Health and McKesson – for $26 billion. The settlement has limits, requiring that at least 85 percent of funds go to programs that help prevent opioid abuse or help those struggling with addiction.

States and local governments are supposed to report to attorneys if they aren’t meeting that threshold.

But that limited accountability brings back fears of what happened with the $246 billion tobacco settlement that started to flow to states in 1998 because of harm the tobacco industry had done to public health.

Those dollars flowed into the state’s general funds, and much of it ended up not targeting tobacco smoking. Instead many of the settlement dollars plugged general state budget holes and built roads. In North Carolina, some cash even went to subsidize tobacco farmers.

The Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids estimates less than 3 percent of the money earmarked to solve this problem has been spent on prevention and programs to help people quit.

Baker worries about a repetition of that grim outcome.

“My biggest fear is we’re going to end up like the tobacco settlement,” said Baker. “We’re just going to blow our money on things that don’t do anything about helping people in recovery.”

Local governments have to report to the council how they spend the funds, but ultimately can allocate dollars how they want.

Part of Baker’s role on the statewide council is to share what he’s learned about addiction and treatment with officials across the state charged with allocating the money. It’s a big reason he’s so vocal about what happened to his son. He hopes to speed up the learning curve.

“It took me and thousands of other families to have a loss like this to get it. And that was wrong,” Baker said.

This story comes from the health policy podcast Tradeoffs, a partner of Side Effects Public Media. Dan Gorenstein is Tradeoffs’ executive editor, and Alex Olgin is a reporter/producer for the show, which ran this story on Nov. 17, 2022.