EVANSVILLE, Ind. — Karen Warpenburg is fighting an almost invisible enemy that’s claiming the lives of a growing number of people in her southern Indiana community: the powerful synthetic opioid fentanyl. Ingesting a tiny amount of the drug can be lethal.

Listen to this story here.

But it’s not that people are seeking it out. Dealers have begun mixing it into other drugs, unknown to buyers. It’s a story Warpenburg knows all too well.

“I had a friend overdose last year from fentanyl,” she said. “He had been in recovery and just used, as far as I know, once. And died from it.”

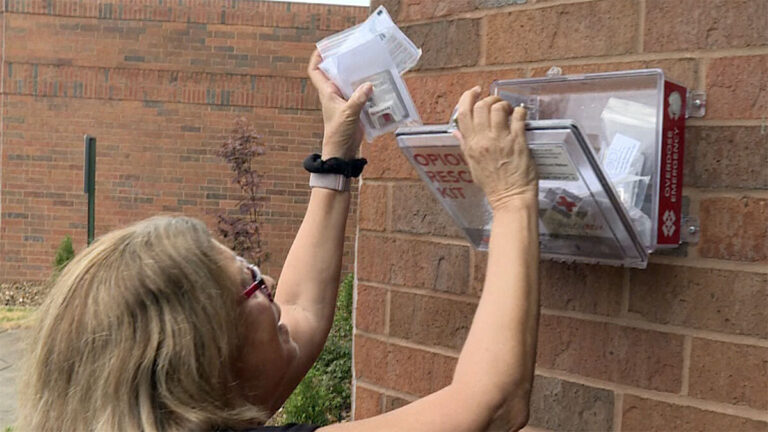

Nearly every day, she checks in on the opioid overdose reversal kits that her nonprofit organization, the Evansville Recovery Alliance, keeps stocked across the city. The kits — small plastic boxes labeled “Opioid Rescue Kit” — are secured to the sides of public buildings and contain doses of naloxone, known by the brand name Narcan. The lifesaving medication can rapidly reverse an opioid overdose.

Nationwide, more than 91,000 people died from drug overdoses in 2020 – a 30 percent rise over the prior year, according to the most recent federal data.

Fentanyl is largely to blame for the historic rise in overdose deaths, said Dr. Debra Houry, the acting principal deputy director of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“A single use can kill,” Houry said at a recent press briefing. “So somebody that may not be used to using drugs, or use them often, we’ve seen the reports of people at a party who do a single pill that’s mixed with fentanyl and die.”

The drug is pervasive. It’s behind the record-high rates of overdose deaths in Indiana as well, and in Vanderburgh County, where Evansville is located. The county of 181,000 people saw a record 106 overdose deaths in 2021, surpassing the previous record of 67 set the year before. Nearly 60 percent of those deaths were attributed to fentanyl.

“It’s in everything,” Warpenburg said. “Pills now, heroin, cocaine.”

Yet she’s finding it difficult to expand her group’s efforts to reduce harm and save lives.

Back and forth on harm reduction

Warpenburg knows how hard it is to overcome a substance use disorder. She became addicted to opioids after being prescribed fentanyl patches following knee surgery in 2005. She’s been in recovery for three years. And for the past five years, she’s been advocating for the expansion of Evansville’s harm reduction services.

Harm reduction is a public health strategy to prevent harmful health consequences of drug use. Interventions include providing injection drug users with sterile syringes to reduce the spread of HIV or hepatitis C.

Some Indiana officials have embraced harm reduction matters in recent years. Intravenous drug use led to a historic HIV outbreak in the southeastern part of the state in 2015. Former Vice President Mike Pence was governor then, and he greenlit Indiana’s first needle exchange.

“I will tell you that I do not support needle exchange as anti-drug policy,” he said during a 2015 visit to southern Indiana’s Scott County, where the HIV outbreak centered. “But this is a public health emergency. And I’m evaluating all of the issues and all of the tools that may be available to local health officials in light of a public health emergency.”

Not long after, health officials started an effort to make Narcan available to the public with overdose reversal kits and Narcan vending machines. Harm reduction advocates touted the effectiveness of Indiana’s efforts, particularly the Scott County needle exchange, which former U.S. Surgeon General and former Indiana State Health Commissioner Dr. Jerome Adams described as the nation’s gold standard.

The Scott County exchange was credited with getting the outbreak under control, bringing new HIV cases from the hundreds to just one in 2020. But county officials said they couldn’t stomach providing needles to people who use drugs, especially with overdoses reaching another record-high in 2021. They voted to close the exchange last year.

‘It’s just not a popular idea’

CDC officials point to the concerning rise in overdose deaths as a clear sign to ramp up harm reduction efforts, including syringe exchange programs.

But Warpenburg worries many in her city, and in Vanderburgh County, don’t understand the effectiveness or availability of local harm reduction services. Some, she said, would prefer not to expand them.

“It’s just not a popular idea for conservative people that just think drug use is bad and people should stop using drugs,” Warpenburg said. “But we need to help those people that are using drugs to get to a place where maybe they want to stop using.”

Vanderburgh County commissioner Cheryl Musgrave said in an email she believes “addiction has corroded the fabric of society and will continue to work with local agencies to combat this problem.”

County officials considered a syringe exchange program in 2016, but decided not to implement one.

“There is debate on whether or not they help reduce substance use by offering people recovery resources when they are exchanging/receiving clean supplies,” Musgrave said in an email. “Given the debate, I would require hard facts that needle exchanges reduce drug use and/or overdoses.”

The CDC cites more than two decades of research showing syringe exchange programs help lower the risk of infections and outbreaks, do not increase drug use, and that those who utilize these programs are more likely to enter treatment for substance use disorder and reduce or stop using drugs.

“I would also ask for facts regarding any other approaches designed to reduce overdoses,” Musgrave said. “Combating this problem is wider than one approach.”

Warpenburg would like to offer syringe exchange services in southeast Indiana, and also add fentanyl test strips to the overdose boxes she helps keep stocked. But under state law, the strips could be considered drug paraphernalia.

According to Warpenburg, the county prosecutor has said he won’t prosecute people for having test strips, but she won’t take any chances without something in writing.

“It’s very frustrating,” she said. “It could be very helpful to someone who’s still using drugs and potentially prevent an overdose.”

Growing concerns from law enforcement

In early July, the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration broke up a multi-state fentanyl ring in Evansville. The group allegedly purchased fentanyl powder in Louisville, Kentucky, to produce counterfeit pills that were sold throughout the region.

Evansville’s location on the southern Indiana border makes it a prime location for drug trafficking, according to Michael Gannon, the DEA agent overseeing the case. Authorities seized over 1,000 fentanyl-laced pills and the presses used to make them.

“We consistently seize thousands of fentanyl pills on a yearly basis and multi-kilogram quantities of fentanyl here in Evansville,” Gannon said.

Gannon said people who deal drugs have been tainting the market with fentanyl for years. The move serves multiple purposes: it helps a dealer stretch a supply and is incredibly powerful, keeping customers coming back for more.

“It’s 50 times more potent than heroin and 100 times more potent than morphine,” Gannon said. “You’re gonna get people addicted.”

But the recent fentanyl bust shows a newer, more concerning development to Gannon: an increasing amount is being produced domestically.

“They’re constantly having significant seizures of fentanyl and methamphetamine here in Evansville,” Gannon said. “We’re talking 50 pounds, 30 pounds, 100- to 150-pound investigations.”

Two milligrams of the drug – the equivalent of a pencil tip – can be lethal.

Ground-level advocates like Warpenburg are key to preventing potential overdoses, he said.

“Law enforcement and the community, we got to come together,” Gannon said. “Because we can’t just arrest our way out of this.”

Warpenburg and the Recovery Alliance scored another victory earlier this summer when they installed the county’s sixth overdose reversal box.

“I think the more that people know and the more work we do, that there’ll be more of a positive outcome,” she said.

Progress is slower than she’d like, but Warpenburg remains optimistic. She said she recently heard from two people who used Narcan her organization provided to save a life.

This story comes from Indiana Public Media, in collaboration with Side Effects Public Media. Follow Mitch on Twitter: @ByMitchLegan.

9(MDM5MjE5NTg1MDE1Mjk1MTM5NjlkMzI1ZQ000))