If you or someone you know is struggling with suicidal thoughts, help is available. Contact the National Suicide Prevention Hotline at 800-273-8255 or the Crisis Text Line by texting HOME to 741741.

HOUSTON — Jennifer Battle is open to just about anything to find people to answer the phones at her Houston-area crisis line.

“It’s like we need to have some kind of dating app, except for crisis work. Like, swipe here if you want to work in the middle of the night and talk to people in need,” joked Battle, director of access at the Harris Center, Texas’ largest public mental health agency.

Listen to this story here.

Battle has been trying for the last 18 months to hire 25 counselors to answer 988, the country’s new mental health crisis line. Her center is one of more than 200 agencies that currently answer the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline and will begin answering 988 on July 16.

A 2020 law converted the 10-digit Lifeline number down to three and expanded the line’s mandate to encompass all mental health care needs, including suicide, addiction and severe mental illness.

Some have described 988 as “911 for mental health,” and lawmakers hope the three-digit number will make it easier for the 50 million Americans with a mental illness to get help. Today, fewer than half get treatment.

As many as 12 million people could reach out to 988 in its first year, according to federal officials, quadruple the number the Lifeline served in 2020.

The people setting up 988 agree the counselors answering these calls, chats and texts will be critical to the new line achieving its goals. But with just six weeks before it goes live, hundreds of positions remain unfilled — putting those looking to the line for help at risk. It also makes it more likely that those who have been hired will end up overworked.

In her 20 years running crisis lines, Battle said this is the most trouble she’s had hiring.

“There’s always been this core pocket of people who are right for us. And now it feels like that pocket of people, I don’t know where they’re going,” she said.

911 as a cautionary tale

As 988 creeps closer to launching without sufficient staffing, some experts worry that workers for the new crisis line could face the same challenges as their cousins at 911.

Understaffing has long plagued 911 call centers, and it intensified during the pandemic. 911 call-takers earn $47,000 a year, on average, and research shows more than half are obese, with many workers reporting high levels of physical pain from sitting through tense shifts, sometimes for eight to 12 hours. One-quarter of 911 professionals have symptoms of depression and post-traumatic stress disorder, on par with rates among police officers and firefighters.

“Whether you want to admit to it or not, it affects you,” said Rita Salazar, who’s been answering 911 calls near Seattle for more than 20 years. Salazar was diagnosed with PTSD last year after a traumatic call nearly forced her to quit her job.

There’s no direct evidence linking 911 call-takers’ health to their job performance, but Northern Illinois University psychology professor Michelle Lilly, a leading 911 researcher, said a large body of evidence from other fields shows, “when you have PTSD and depression, it affects your decision-making, your concentration, your attention, your sleep. And all of these things are critical in being able to perform successfully, particularly under pressure.”

Rebecca Neusteter, the executive director of the Health Lab, a health care and criminal justice research group at the University of Chicago, worries the efforts to form the 988 workforce are being built on the same swampy foundation as 911.

The Biden administration has committed about $400 million to scaling up 988, but like 911, there is no new sustained federal funding. Instead, both lines primarily rely on state and local funding, and neither has uniform national training standards.

“If we’re not attending to the staff, ultimately that has huge detrimental impacts on communities,” Neusteter said. “People won’t call anymore, which could leave people in crisis with even fewer resources to seek help.”

Learning from 911’s mistakes

988 leaders are taking concrete steps to build up a robust workforce.

To avoid overworking and burning out staff, many 988 centers are raising starting salaries by as much as 30 percent and offering remote work options to attract more applicants. At least one center in Washington state has hired counselors based in Virginia.

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, or SAMHSA, the federal agency that oversees 988, is trying to drum up interest in the work with a new website that links to the open positions. A spokesman said they plan to post on social media and talk up the job to college students and administrators. In a nod to how much work remains, the agency has pushed back its public campaign to promote the line until 2023, the year after the three-digit number goes live.

There are also efforts to standardize the training 988 call-takers receive, with the first-ever mandatory training program set to roll out this fall. Historically, the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline has recommended evidence-based trainings, but each center has been in charge of its own training program.

One of the greatest areas of focus is supporting the mental health of 988 counselors.

Unlike 911, where some have questioned whether call-takers can even suffer ill-effects from the work, 988 leaders say staff mental health has and will continue to be a top priority. But they know that with low staffing levels, more calls and the high-pressure nature of those calls, they will need to do more to ensure their staff don’t face similarly high levels of depression and PTSD.

“I was first and foremost afraid that the counselors’ mental health would suffer, that they would experience higher levels of burnout,” said Courtney Colwell, the 988 program manager for Volunteers of America Western Washington.

In response, Colwell has added more managers to help staff handle tough calls and jump in if someone needs a break. She also established a staff advisory committee to get call-taker feedback and give them a voice in policy decisions.

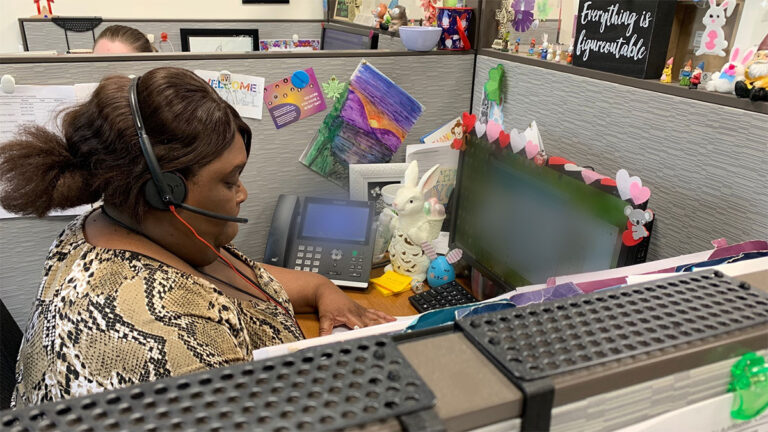

In Houston, Jennifer Battle says her supervisors hold regular debriefings with call-takers and write four to five personalized thank you notes to them each week.

Like many call center leaders, Battle does not expect to be fully staffed when 988 goes live on July 16. She is confident she will get there eventually, but what’s impossible to know is how long that will take and how many people in crisis will suffer until it does.

This story comes from the health policy podcast Tradeoffs, a partner of Side Effects Public Media. Dan Gorenstein is Tradeoffs’ executive editor, and Ryan Levi is a reporter/producer for the show, which ran a version of this story on June 2. This episode is part of a series on 988 supported, in part, by the Sozosei Foundation.

9(MDM5MjE5NTg1MDE1Mjk1MTM5NjlkMzI1ZQ000))