In highly politicized times such as these, teachers are often warned to remain neutral in the classroom. But at a public primary school in Kewanee, Illinois, one art teacher is showing kids it’s their duty to speak out about injustices.

Kewanee is in Henry County, about a two-and-a-half-hour drive west of Chicago. According to the US Census Bureau, the town has about 12,500 residents, about 85 percent of which are white, over 10 percent are Latino and about five percent are black.

The art room at the town’s Central Elementary School sits at the end of the hall, past the front entrance. It’s about the size of a basketball court, though much more colorful, and it feels like the hub of the school, with students popping in and out in between classes.

Marc Nelson, the 38-year-old art teacher, has a casual teaching style. On a recent Wednesday, he gave an introduction for the day’s objective and then let the kids work collaboratively and discuss amongst each other.

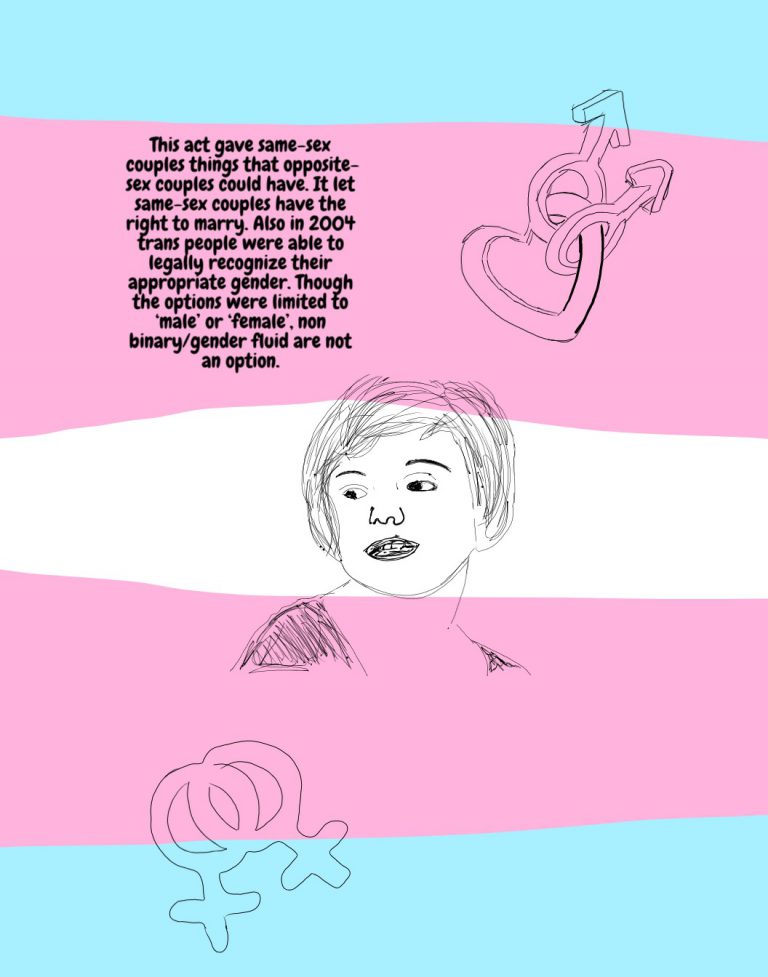

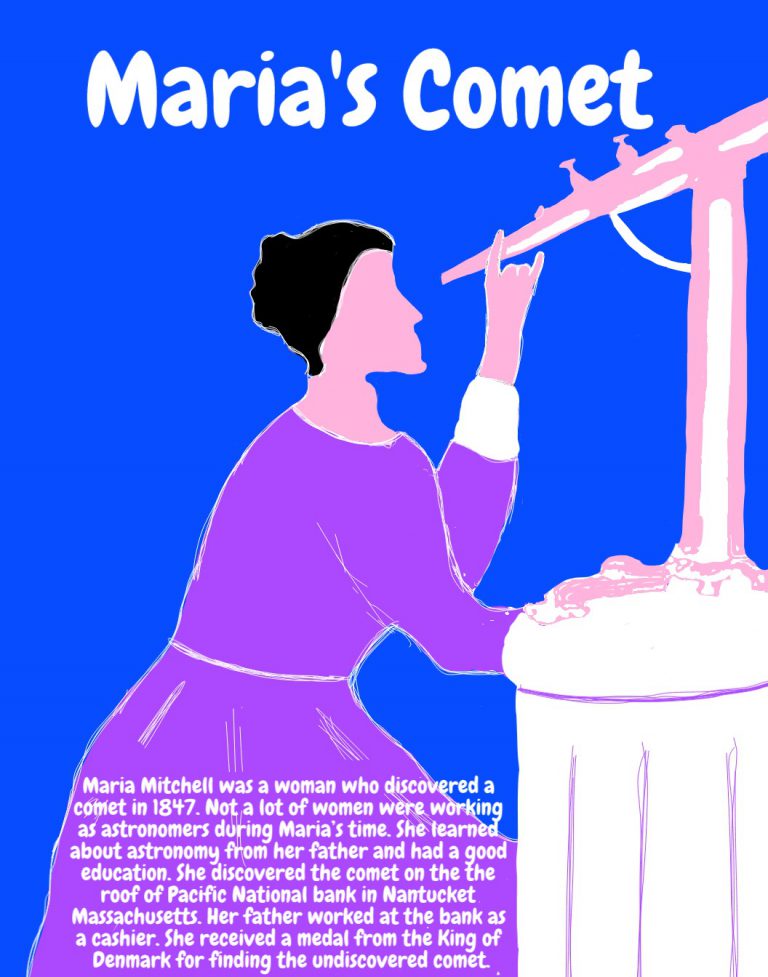

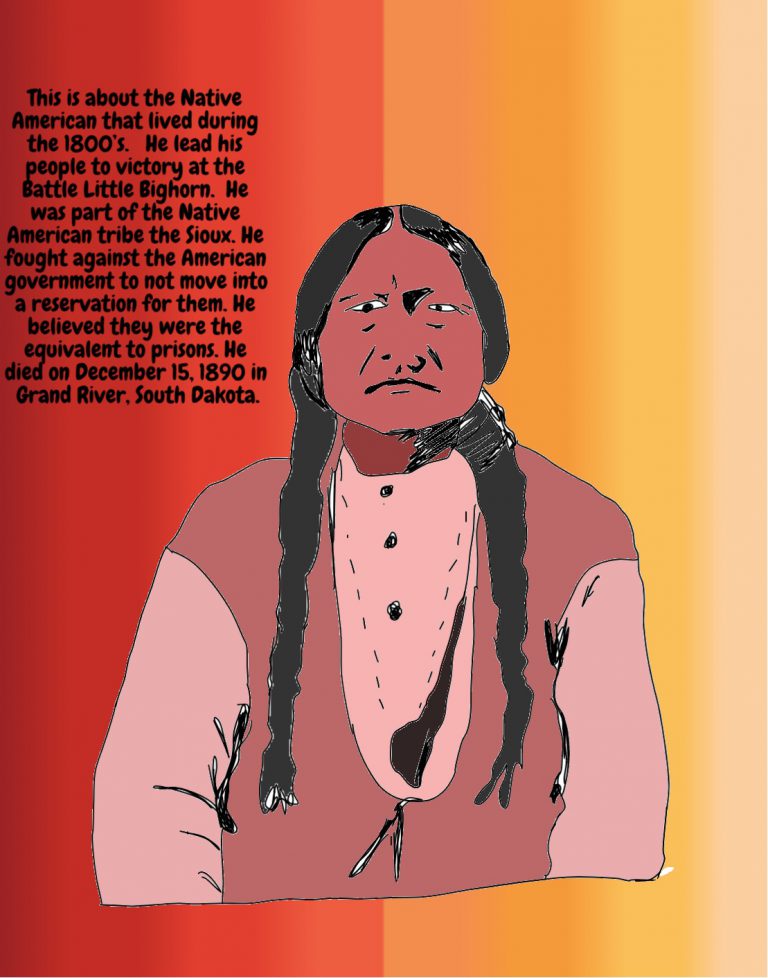

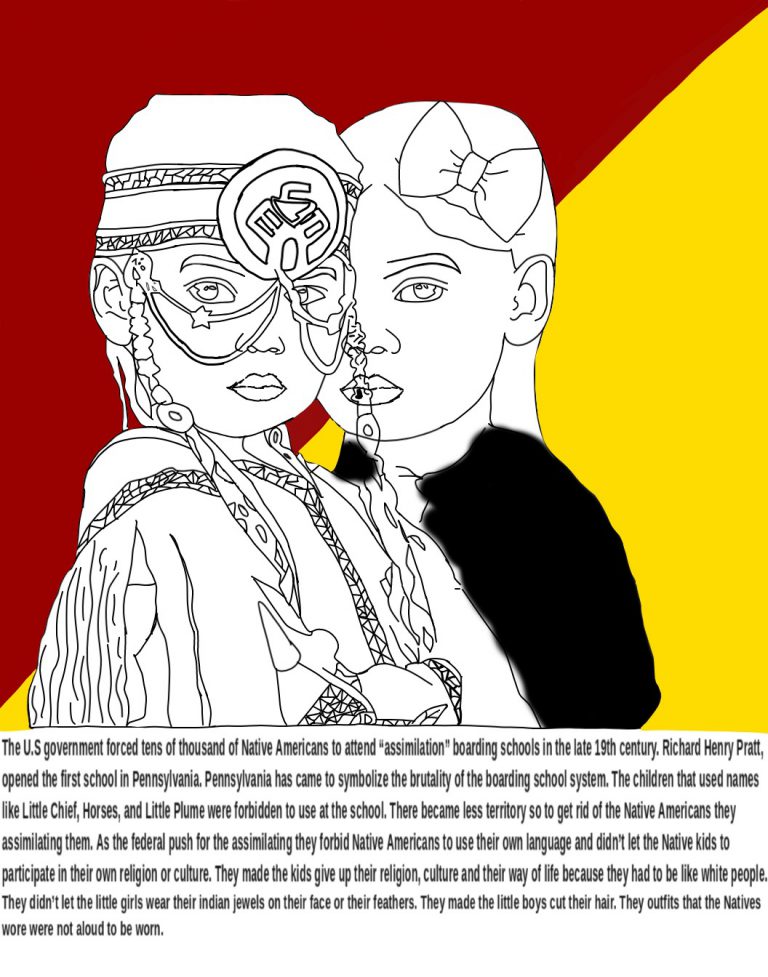

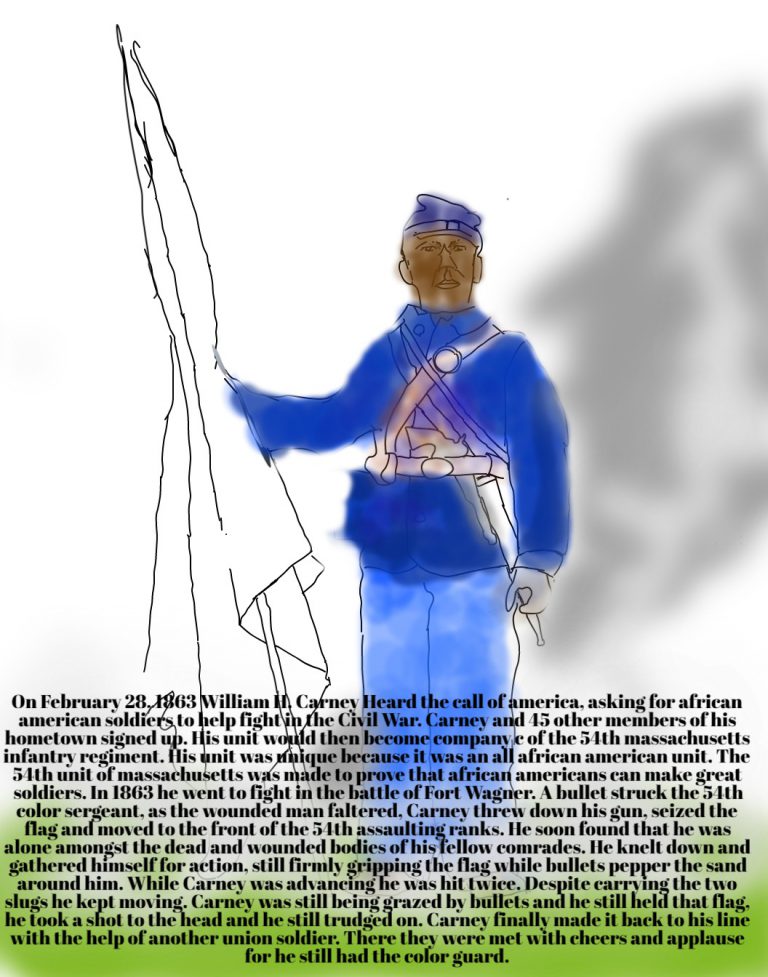

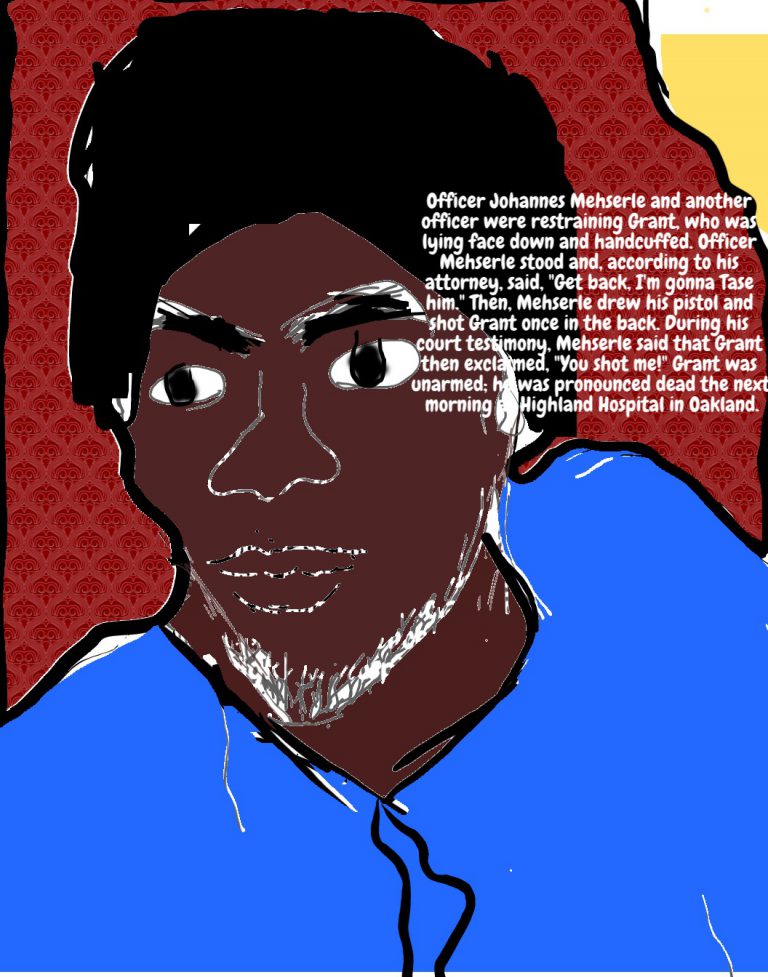

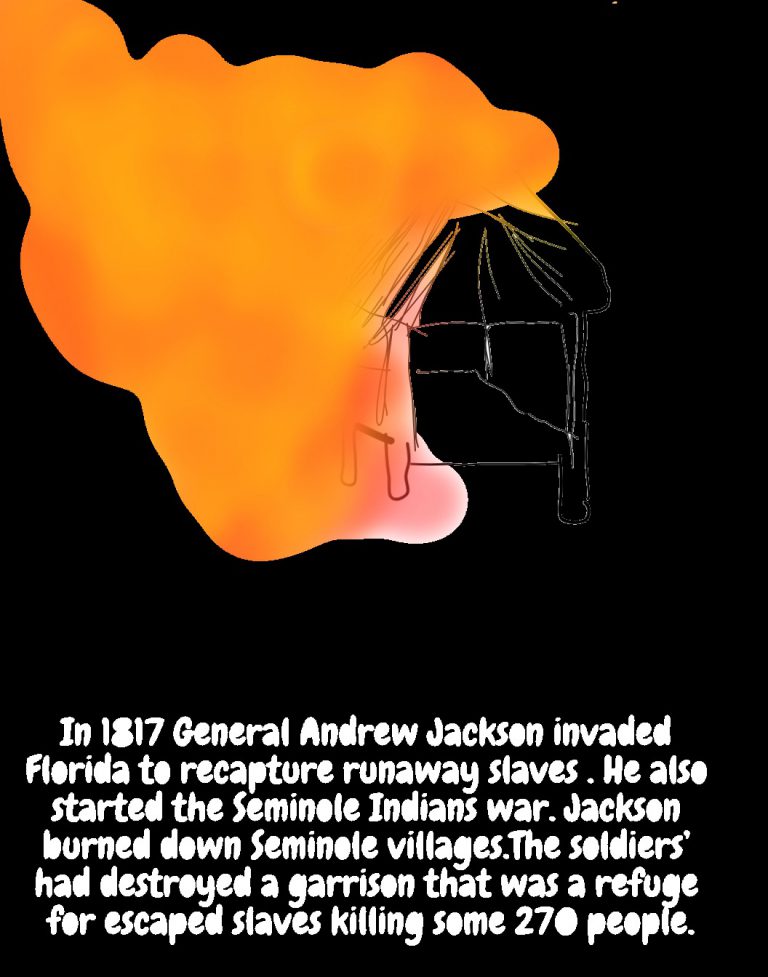

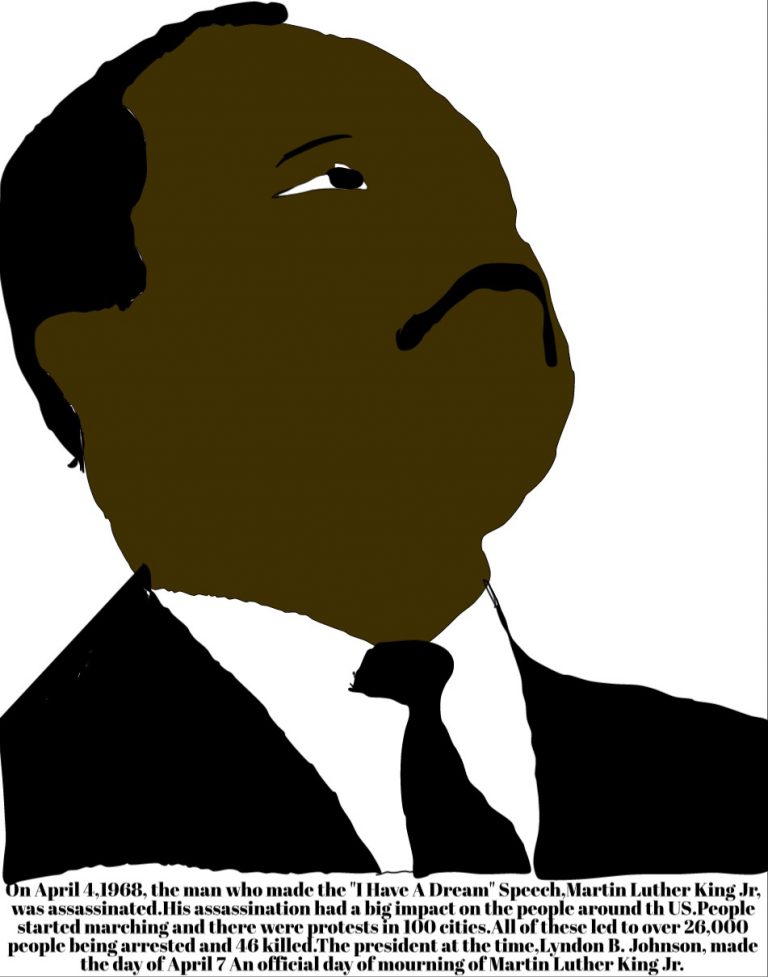

The students worked on tablets, writing summaries and adding final touches to their “People’s History” projects, which highlight marginalized figures from the near and distant past.

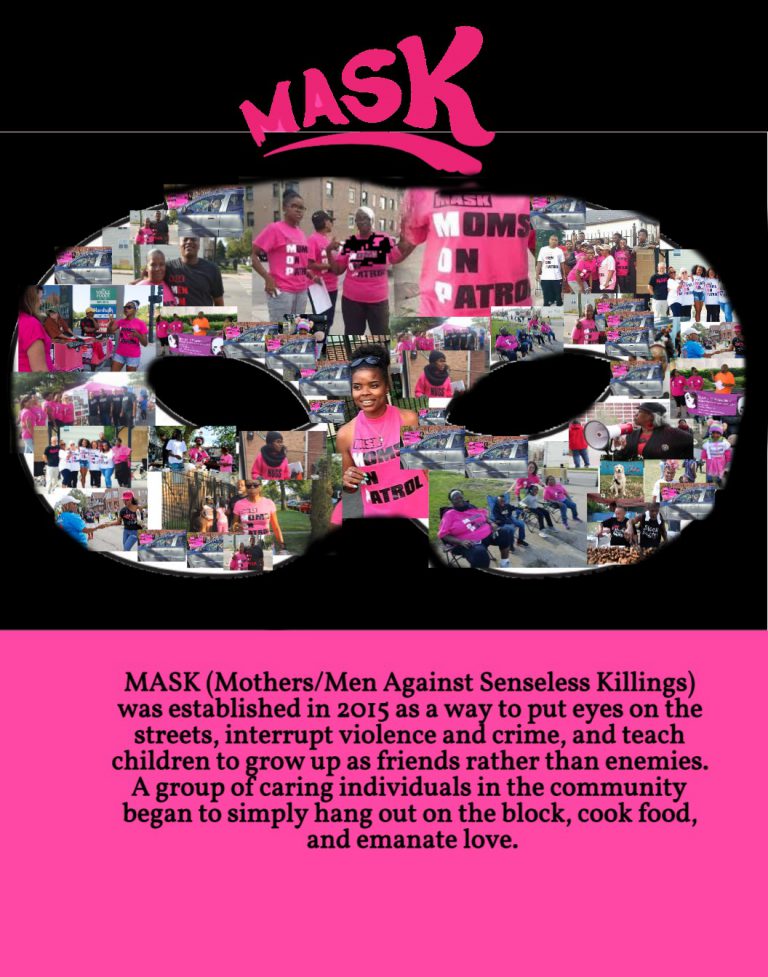

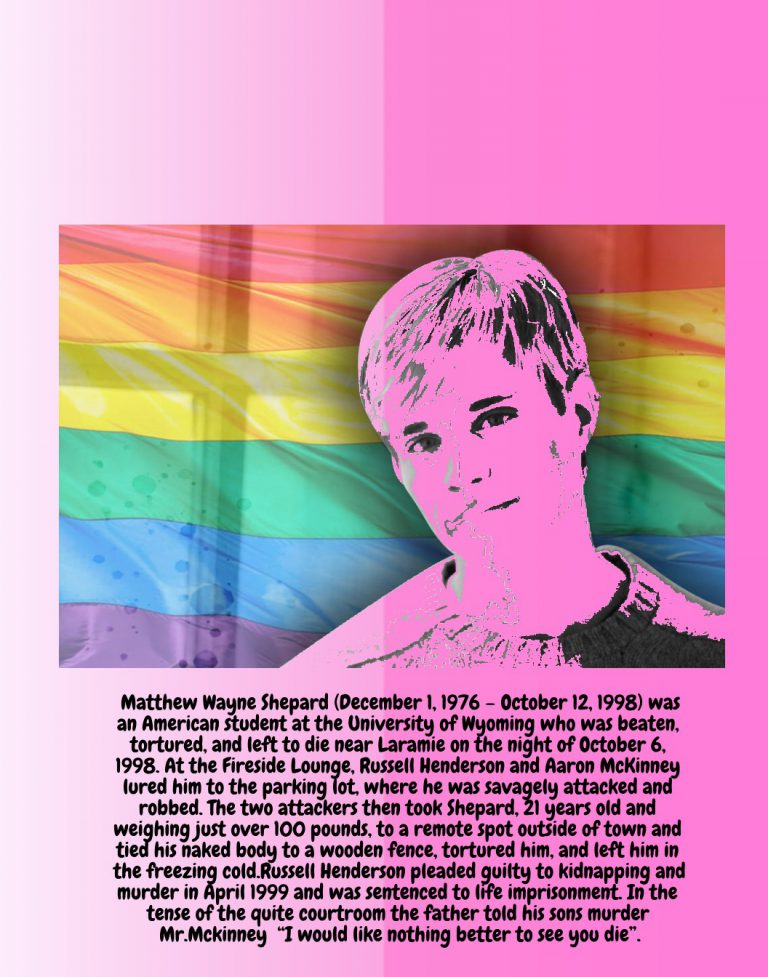

The 13- and 14-year-old students focused on people and events that illustrate the diversity in American life. People like feminist icon Betty Friedan and Ellen Ochoa who was the first Latina to go to space, and events like the Stonewall Riots, a major milestone of the LGBTQ liberation movement.

The project is just one of many ways Nelson has taught the kids about humanitarian causes and social justice. He’s used a variety of media, from digital posters to music and movies, to comic books like politician and civil rights activist Jim Lewis’ March series which he reads to his students.

“I want to show kids what art is really about,” Nelson said. “When you talk to any artist, they’re not just going to talk about their obsession with cadmium orange. They’re going to talk about something that inspires them.”

In his own time, Nelson creates artwork depicting lives ravaged by warfare and shares them on social media. He has earned international attention for his work. His latest focus is oil paintings of children and other victims of the war in Syria. Some of those pieces, depicting the bloodied and wounded, are currently being created in the classroom, where students can follow along with his progress.

Nelson also connected his class via Twitter with two young Syrian sisters named Noor and Alaa who have an active account detailing what they’ve witnessed and begging for the carnage to stop.

Last year, his students made a stop-motion animated movie about the life of the sisters. The film detailed aspects of their lives, like their desire to walk to school without the threat of violence. That film is narrated by Central Elementary School eighth-grader Myracle Sharrow.

At one point, she says on behalf of the girls, “We love school. One day our friend was killed with her mother while walking to school.” Sharrow said she still communicates with Noor and Alaa on a near daily basis and showed me their messages on her phone. The two sisters are now refugees in Turkey, where they no longer face daily bomb threats.

Sharrow said getting to know the sisters and working on the film was inspiring. “I’ve never met anybody that has gone through any of that, (who) was scared to go to school,” she said. Sharrow said the experience also opened the door to conversations about the war with her family.

I asked the school’s principal, Jason Anderson, if bringing up these types of topics made any families uncomfortable or led to push back on the curriculum.

Anderson said so far there hasn’t been a problem. And he supports Nelson, because he, “Really helps the kids understand what’s out there in this world. We’re 78 percent low income.” Anderson said connection with various types of people and political issues, “Gives them a sense of, hey, you know what, we’re not alone. We’re all in this together … it gives them an idea of what’s out there.”

Anderson said he hired Nelson for the enthusiasm he brings to the classroom. Nelson’s interest in human rights was sparked as a child, when his grandfather told him about his own experience as a refugee, leaving his home of Northern Ireland for the United States. “I grew up with his story of fleeing a conflict zone,” said Nelson.

Social media and the internet made current events more visible than ever, but art has long been used as a tool to draw attention to and educate about social justice and other activist causes.

Rebecca Zorach is the Mary Jane Crowe Professor in Art and Art History at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois, where she teaches on the intersection of art and politics. She’s explored social-justice centered art created in Chicago, especially by artists of color, including those active in the Black Arts Movement in the city in the 1960s and ‘70s.

Zorach says of the work Nelson is doing, “It’s a really good lesson for those kids in ideas about freedom of expression. And if they should run into questions of censorship or controversy, that’s also a really good lesson in freedom of expression.”

While there has yet to be conflict brought up by Nelson’s teaching style, he said the junior-high-aged kids he teaches are naturally interested in controversial, politically charged topics.

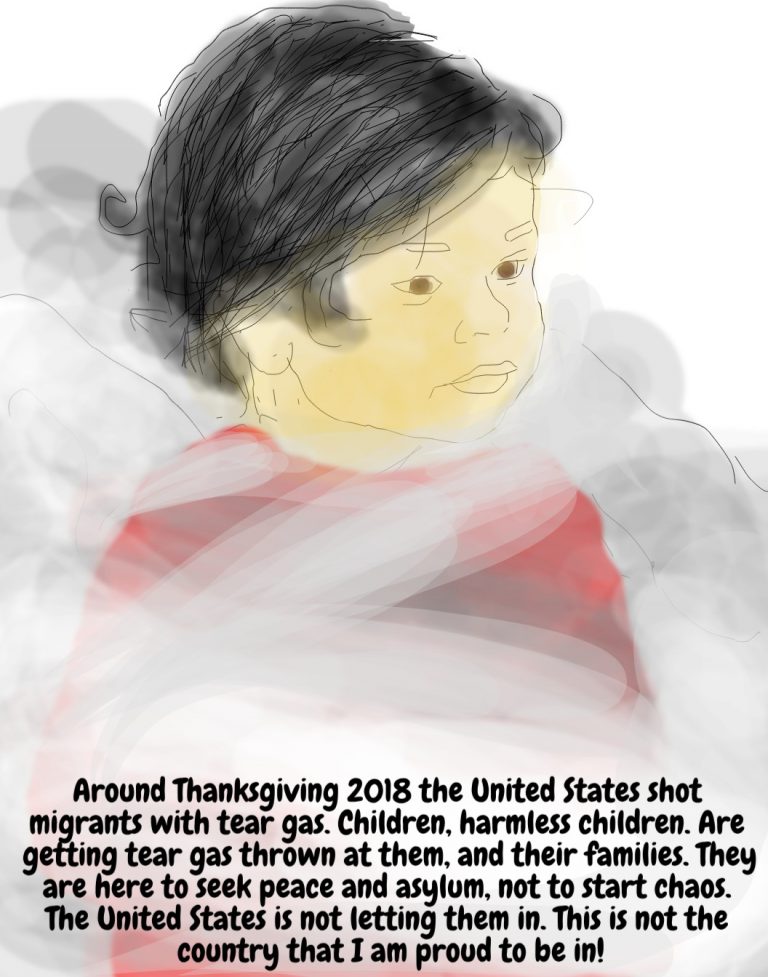

“We came back from Thanksgiving break, and a lot of my students had seen videos of the tear gassing,” said Nelson, referencing viral photos and videos depicting women and children being attacked near the US/Mexico border. “And of course the images that were sticking in their mind were of kids.” Nelson said some of his students are themselves immigrants from Mexico and Central America.

“So I showed them the images, we talked about what’s going on, we talked about using language in a certain way, the way we paint people with words is really important,” said Nelson. “I’m not trying to push a political agenda, I’m trying to push a human agenda, trying not to dehumanize people.”

Nelson is also furthering his own education. He’s enrolled in a master’s program at Eastern Illinois University in Charleston, where he has designed his degree to focus on storytelling and its ability to cultivate empathy – especially for people who have been designated as “other” by the larger society.

“After working on projects over the years with my students, the more we would tell stories visually, whether through comics or film, I noticed that my students would respond emotionally, they would become interested in what they’re reading, they would basically be cultivating empathy,” said Nelson. “I’m working on a project right now with refugee centers, and we’re trying to design the project as we speak.”

For Nelson, the “human agenda” means getting to know what his students worry about in their own lives.

13-year-old Petra Petty is a budding activist. She also has cerebral palsy and uses a wheelchair. After having problems getting into the school’s gym, she approached the principal about how to improve the school’s accessibility. She also successfully urged a local park to add a swing for those in wheelchairs.

“When you’re not handicapped, you don’t think about that type of stuff,” said Petty.

She said it’s her art teacher, Mr. Nelson, who bolstered her confidence to speak out, having brought up issues like the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) in class. “I would like to speak for people who are afraid to,” said Petty.

For Nelson, it’s a real-life example of putting into practice his lessons to be a voice for the voiceless, and showing that speaking publicly about injustice, even – and sometimes, especially – through art, is empowering.