As harvest wrapped up this year and the leaves turned brilliant shades of red and yellow, two of the world’s biggest agribusinesses, Archer Daniels Midland (ADM) and Smithfield Foods, announced they were pairing up on projects with environmental nonprofits.

It didn’t create the furor like in past years when oil companies joined forces with nonprofits and were met by accusations of “greenwashing” — that is, just trying to shine up their reputations.

But that doesn’t mean these latest partnerships have it figured out. Success begins with finding common ground with the farmers and landowners the efforts affect the most. And there’s also the challenge of holding each other accountable.

Harvest Public Media’s Erica Hunzinger explores partnerships between agribusiness and environmental nonprofits.

“I think it’s more effective to have a change when you to come in and talk with people and come to an agreement about an overarching goal and then figuring out how to get there as opposed to fighting about it,” said Stewart Leeth, the chief sustainability officer for hog processor Smithfield.

These voluntary, piecemeal partnerships among non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and corporations may even turn out to be the first line of defense against climate change — particularly as the federal government shrinks its regulatory duties at the direction of President Donald Trump.

What’s behind it?

On the surface, corporations’ environmental-minded work appears to have increased substantially in the 2010s. The Governance and Accountability Institute said earlier this year that nearly 85 percent of companies in the S&P 500 — including ADM and Smithfield — reported on sustainability or corporate responsibility in 2017, up from 20 percent in 2011.

Partnerships with environmental organizations are among the most visible steps a company can take, and they’re taking root among a host of food and agribusiness companies, like PepsiCo, Nestle and two of the most recently announced efforts.

Smithfield announced Nov. 1 its partnership with the Environmental Defense Fund, a nonprofit advocacy group, on protections for monarch butterflies. And on Oct. 17, ADM joined the Ag Water Challenge, which is hosted in part by the Coalition for Environmentally Responsible Economies (Ceres), a sustainability nonprofit that targets investors and companies.

Both EDF and Ceres told Harvest Public Media that the cost of the work falls mostly in the lap of the multibillion-dollar companies, not the nonprofits.

“We do not want this to be companies paying to engage with us,” said Eliza Roberts, senior manager of water at Ceres. “Ceres and (the World Wildlife Fund) received funding from foundations to do all of the work that we do and we’ve launched this challenge as a way of incentivizing companies to step up and make commitments to address the water challenges that we’re facing now and in the future.”

But one big concern is accountability, and critics like Stephanie Feldstein, with the nonprofit Center for Biological Diversity, said that’s the weak spot in the partnerships — and where consumers should push back.

The goals “don’t tend to be ambitious enough,” she said, adding that companies need to publicly report results “so that their customers … their investors, can see whether or not they’re actually sticking to these targets.”

Feldstein, whose nonprofit doesn’t seek such partnerships, said in many cases, the partnerships are just a PR stunt, “more of a partnership of convenience for the corporation.”

The Missouri model

In 2016, Smithfield, whose large-scale hog operations are the target of nuisance lawsuits and waste complaints, announced a goal to reduce its overall greenhouse gas emissions by 25 percent by 2025.

To that end, the company has been working in northern Missouri since 2014 with Roeslein Alternative Energy (RAE) to try to capture the methane from hog-waste lagoons and turn it into biogas. It’s a technique that’s spread to several other operations in Utah and North Carolina, and the Washington Post reported that an energy company is now involved.

But RAE founder Rudi Roeslein, who invested millions of his own money into the biogas-capture project, wanted to take it a step further to protect pollinators — specifically, monarch butterflies. And that’s where the Environmental Defense Fund entered the picture.

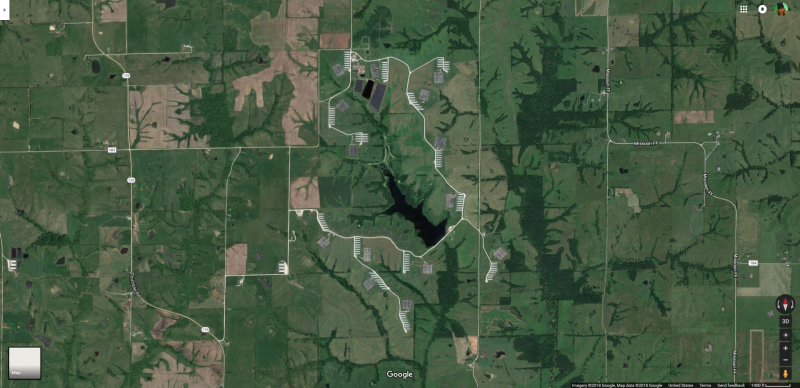

The three organizations decided on restoring habitat at a hog farm just south of Green City, Missouri, with the hopes of providing habitat for monarchs, which could be listed as a federally protected species in 2019, and trying out prairie brush as a biomass energy source.

“(EDF is) constructive in that they figure out what goal they want to reach and then they figured out a way to partner to get that thing accomplished as opposed to fighting and pointing fingers and filing lawsuits and things like that,” said Smithfield’s Leeth.

Smithfield, which had about $15 billion in revenue in 2017, is paying $300,000 through its philanthropic arm for planting grasses and wildflowers on more than 600 acres. David Wolfe, EDF’s director of conservation strategies, said that is a big help because “there’s only so much funding available from private sources, public sources to just pay to help a farmer restore habitat.”

But why focus on monarchs, which have already received a river of media coverage about their decline?

Tatyana Deryugina, an environmental economist at the University of Illinois, said it’s about positive publicity because companies tend to do things “that are most visible to the public as opposed to the things that are really the most cost-effective if we don’t include the (public relations) value,” she said.

“So, monarch butterflies are a great example. People really care about them, they’re awesome. Why is the hog producer doing this? … The types of activities that the firms pick might not match up with what society would like them to do,” she added.

Leeth, however, argued the connection is a natural one for the North Carolina-based company.

“I don’t think people really realize the distance between the folks who actually work on farms and grow crops, and folks in the urban areas who actually acquire and buy the food and consume the food grows more and more,” he said. “I don’t think people realize how important pollinators are, whether it’s bees or butterflies or anything else.”

The partners differ, though, on the long-term goals of the monarch project. Wolfe said the nonprofit wants to restore 1.5 million acres of monarch habitat through 2028, while RAE wants to have 30 million acres of land changed to prairie grass by 2048. And Smithfield is looking to meet its emissions goal and have more “manure-to-energy” projects, Wolfe said.

ADM’s water focus

For ADM, water sustainability is perhaps a couple of steps divorced from its actual business of processing and selling grains, but it’s a major component for healthy soil in which the grain is grown.

The Ag Water Challenge asks companies to “assess … efforts to address water risks in agricultural supply chains” and make that change. It’s has been going on since 2016, and ADM finds itself among other major food companies like General Mills and PepsiCo.

ADM Chief Sustainability Officer Alison Taylor acknowledged that working with competitors or entities seems like “strange bedfellows.” But, she said, ADM is serious about its partnerships, of which it has many.

“We can get a lot more done this way” and “mutually benefit because we kind of have different sweet spots,” Taylor said, explaining that ADM uses the expertise of nonprofits and data-heavy partners and the partners use ADM’s expertise and connections with farmers.

ADM’s goal in the Ag Water Challenge is to focus on what Taylor called “stressed watersheds” in the places it sources wheat, corn and soybeans, including Colorado, Illinois, Indiana, Kansas, Missouri, Nebraska and Oklahoma.

It’ll be done with a couple of different programs that emphasize farmer outreach and training, Taylor noted, and includes incentives for farmers. One of those programs, Saving Tomorrow’s Agriculture Resources (or STAR), is new to ADM but was started by the Champaign County Soil and Water District in central Illinois, about 30 minutes away where ADM’s headquarters were located for decades.

Like the Smithfield effort, ADM is paying about $30,000 for the Ag Water Challenge efforts through its corporate social investment program, Taylor said. The company had about $60 billion in revenue at the end of 2017.

Tracking progress

Ceres published a report in August that concluded a majority of corporations that have sustainability efforts “provide no formal assurance of sustainability disclosures” — that is to say, you can’t trust that what the company puts forth to investors is true.

And it’s investors that make the nonprofit-corporate coupling a triangle, and they often have the ear of people like Taylor.

“They contact me directly to talk about our progress,” she said. “For instance, the progress reports are on our website with respect to our no-deforestation policy, they read them and they call to ask about what our future plans are or whether we’re going to develop more specific goals.”

Ceres is evaluating and measuring ADM’s progress, Roberts said, which includes adding that date to its biannual rankings report. The five evaluative components she described sound straight out of a corporate sustainability handbook — phrases like “value chain” and “time-bound, measurable commitments” and “mitigate risk.”

Notable in Taylor’s description of the STAR program was that farmers will “voluntarily determine” their level of preventing soil-and-nutrient participation. And that type of commitment is what can lead to weak partnerships, said Feldstein with the Center for Biological Diversity.

“A lot of times, we see that the goalposts keep moving, and it keeps getting more and more diluted. We found in terms of accountability is to ask from the beginning for these ambitious goals, get the strongest targets that we can get,” she said.

Whose role?

While acknowledging that the partnerships may be successful in solving some environmental problems or making a company more sustainable, Deruygina, the University of Illinois professor, doesn’t think environmental policy should be left up to corporations.

“Without government regulation, they have no incentive to care beyond looking good in front of their customers,” she said.

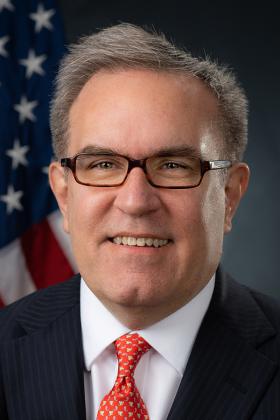

The Environmental Protection Agency says that couldn’t be further from the truth. Acting Director Andrew Wheeler said his agency, which has put into place “28 deregulatory measures” since President Donald Trump took office, encourages the partnerships.

“We don’t think that everything should be directed out of D.C. or by the federal government. We think that a lot of great progress is being made by cooperative measures between companies and outside organizations. … We champion things like that but I don’t think the federal government needs to step in and manage or control private-sector initiatives,” he told Harvest Public Media in early November.

Deruygina said there is a best-case scenario: a financial and environmental win for the nonprofits and corporations.

“Sometimes these partnerships are about sacrificing profit. They’re about teaching a company how to do something that’s more environmentally friendly and potentially cheaper,” she said.

And that’s where accountability returns, in the sense that it’s important to the nonprofits seeking these partnerships, Feldstein said.

“A lot of the positive image that they’re looking for is being able to say ‘We reached this company, we got them to make a commitment. We got them to create the change that will reach … all of the angles of their business,” she said.