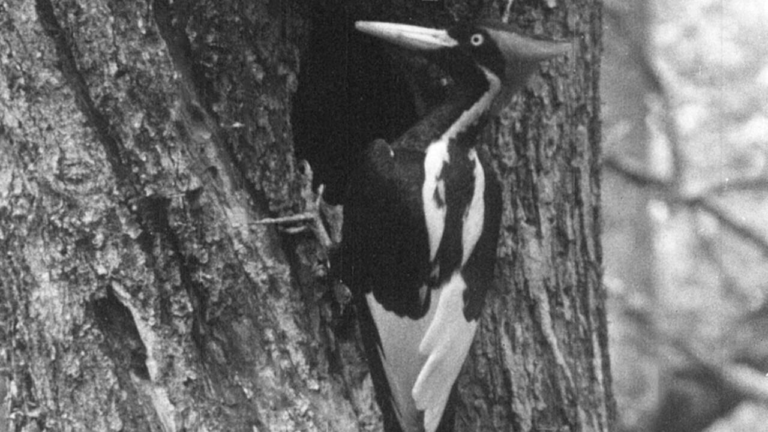

A century ago, people throughout the Midwest could hear the high-pitched staccato call of the ivory-billed woodpecker echoing in old-growth forests throughout the Mississippi River basin, from Montana to Louisiana. Now that call has been permanently silenced.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service recently declared 23 species, including birds, freshwater mussels and a flower, extinct. Two of those species — the ivory-billed woodpecker and the tubercled-blossom pearly mussel — used to find habitat in the Midwest.

Both species were driven to extinction in different ways, but human disruption of their habitats is the undeniable underlying cause.

For the ivory-billed woodpecker, the biggest factor was habitat loss and habitat degradation, says Jeff Hoover, avian ecologist for the Illinois Natural History Survey.

Ivory-billed woodpeckers primarily lived in old-growth bottomland forests, which have been reduced by as much as 85% in some areas, according to Hoover. Large areas of bottomland forests were cut down for lumber and converted to agriculture during both World War I and World War II.

“As the habitat went, so went the ivory-billed woodpecker,” Hoover says.

So it also went for the tubercled-blossom pearly mussel, a freshwater mussel species that used to live throughout the Ohio River basin, including in Indiana and Illinois. The biggest contributor to their decline was human-made dams.

“Freshwater mussels like to live in flowing water because they’re sedentary … so they kind of need the water to bring the food to them,” says Alison Stodola, a malacologist with the Illinois Natural History Survey. “So if the water changes from this flowing river ecosystem into a lake, they can no longer survive because the water isn’t oxygenated enough and it can’t feed them properly.”

Stodola says a decline in water quality, due in part to increased agricultural runoff, has also led to the decline of freshwater mussels in the Midwest. Mussels, including the tubercled-blossom, were also harvested for many years by the button industry to make pearl buttons.

Added together, these human impacts have led to freshwater mussels being among the most endangered groups of organisms in the country.

Ecological impact

The loss of these two species in the Midwest wasn’t surprising to scientists. The last verified sighting of the ivory-billed woodpecker was in 1944. And though you can still find fossilized shells of the tubercled-blossom pearly mussel in the wild, neither species had been seen alive in the Midwest in at least a century.

Still, their official delistings from the endangered species list is a sign of a deteriorating ecosystem.

“Freshwater mussels are filter feeders, so they are filtering contaminants, heavy metals, different types of bacteria, algae … so the loss of freshwater mussels is kind of one of these warning signs that our rivers are not healthy,” Stodola says.

It’s also seen as a warning sign to other species living in those habitats.

“When you lose what might be called an umbrella species, that species that kind of encapsulates old growth bottomland hardwood forests, if that thing goes away, then there’s a lot of other things that were under that umbrella that are also now going to potentially be in peril,” Hoover says.

All kinds of species — including river otters, swamp rabbits, fish and reptiles — call bottomland forests home. Hoover says we should also be concerned about their futures.

In addition to ecological impacts, Stodola says, the disappearance of these species also permanently alters the physical landscape of the Midwest. She says she’s read records from early freshwater mussel scientists that describe riverbeds covered in pearly white mussel shells.

“It’s just kind of sad to know that we may not be able to experience that level of diversity and abundance in our lifetimes.”

Dana is a reporter for Illinois Public Media. Follow her on Twitter @DanaHCronin